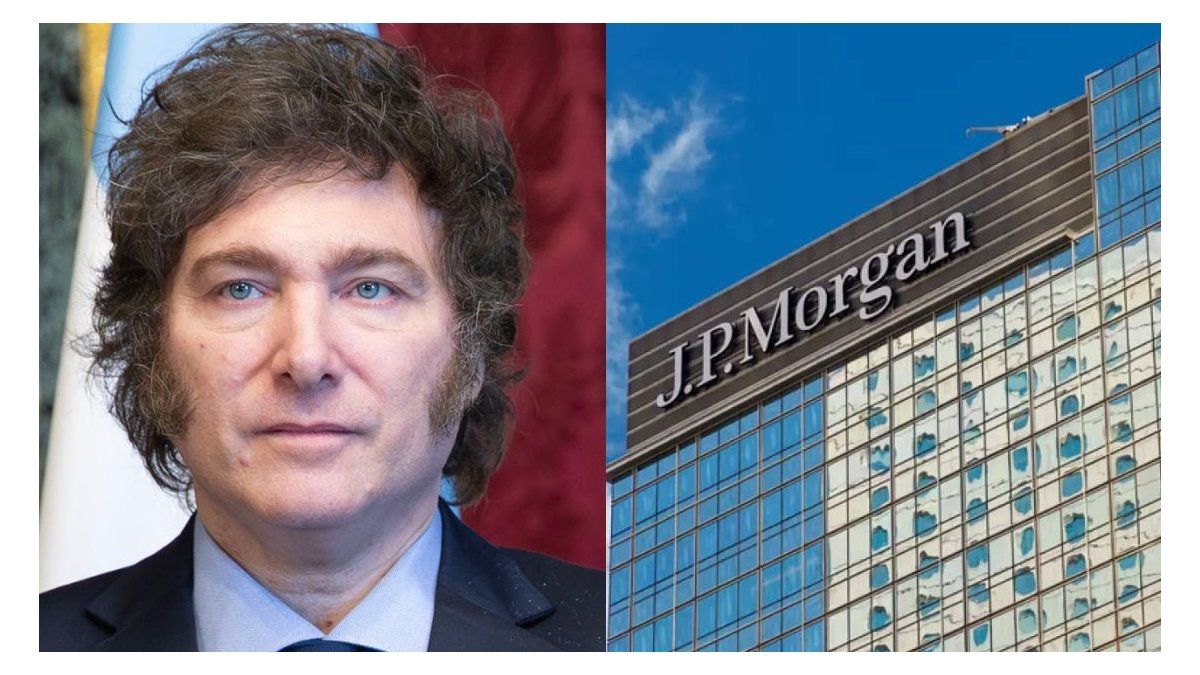

Quietly, the Government took a step towards financial stabilization this Monday by formally announcing the appointment of JP Morgan Chase as structuring bank of a bond repurchase operation sovereigns in the secondary market. It will be financed with loans from multilateral organizations.

The Ministry of Economy detailed that this maneuver seeks to extend key maturities and reduce pressure on net reserves. In this way, it is aligned with the commitments of the agreement with the IMF and, in the opinion of the Government, it could reopen the door to a gradual return to international markets.

At the same time, it was confirmed an agreement closed for a foreign exchange swap of US$20,000 million with the United States Treasurywhich will inject liquidity into the Central Bank (BCRA) and serve as a cushion for purchases in the secondary market, in a gesture of explicit support from Washington for the mileist reforms. This duo of announcements – the unprecedented buyback and the agreed swap – transforms concessioned funds into a tool to reduce the weight of the debt.

While Jamie Dimonthe all-powerful CEO of JP Morgan, lands this week in Buenos Aires for a summit with his local team, the echo of this maneuver resonates. The originality of this operation lies in its -apparent- simplicity. The Argentine Treasury and the BCRA, with net reserves in negative territory and a country risk that is already back at 1,048 basis points, access a flow of dollars disbursed by multilateral credit organizations.

The key to the announcement: a reversal of the Brady Plan

Instead of having a specific assignment, These funds would be channeled directly into debt purchases in the secondary marketwhere Argentine bonds are trading at a discount due to investor skepticism. JP Morgan, one of the largest entities, would select eligible securities, would launch exchange offers at negotiated prices and execute transactions that could cut billions from gross debt.

In some way, the Government builds a kind of “bridge” between the official world of multilaterals – with its fiscal conditionalities and quarterly reviews – and the chaotic and volatile secondary market, where hedge funds and banks, such as JP Morgan itself, speculate.

What is unprecedented is not only the scale –potentially US$20 billion in a hybrid package with US Treasury swap and other lines–, but the fact of using “cheap” multilateral money for a precision operation that – they believe in the Treasury Palace – would avoid the stigma of an explicit default.

The JP Morgan variant: the financial arm of the Government

JP Morgan is not a casual actor in this plot; He is the conductor of the orchestra. Luis Caputothe brain of the operation, forged his sword in that bank’s trading between 1994 and 1998. Pablo QuirnoSecretary of Finance, rose as director for Latin America at the New York headquarters; Santiago Bausiliaccumulated 11 years at the bank; Jose Luis Dazais former director of Emerging Markets Research, or Vladimir Werningwho was chief economist for the region. This constellation of “graduates” shapes incentives, such as implicit guarantees from the US Treasury, for bondholders – many of them funds that JP Morgan advises – to unwind their positions without making a fuss.

At the center of this network is located Daniel Pintothe operational co-CEO and president of JP Morgan, born in Buenos Aires in 1960 and the architect of its rise from a currency analyst at Manufacturers Hanover in 1983 to the pinnacle of the institution. Pinto, who ran trading in Argentina before expanding into Latin America and global emerging markets, embodies a bond between the bank and the government: At an executive summit in Florida in 2022, he reflected on the previous decade as a period of “intensity comparable to that of a war,” evoking his direct experience with Argentina’s hyperinflation of the 1980s.

Brady and the debt machine

To appreciate the novelty of this move – and its potential to go beyond historical limits – one need only look back. The Brady Plan of 1989 emerges as the undisputed grandfather of these operations, but with nuances. Launched by Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady in response to the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, The plan encouraged commercial banks to reduce debt in exchange for structural reforms and multilateral supportmarking a shift from mere refinancing (the failed Baker Plan of 1985) towards the explicit reduction of stock.

In the Argentine case of 1992, under the presidency of Carlos Menem, materialized in an agreement that exchanged US$21,000 million of debt with commercial banks –plus US$8.3 billion in late payments– for 30-year Brady bonds, cutting the nominal amount by about US$3 billion and up to 35% in net present value.

He IMF and the World Bank played a pivotal role, providing “fresh money” for initial payments (between 7% and 13% of the principal) and collateral guarantees –such as zero-coupon US Treasury bonds– that backed the new securities, thus stabilizing cash flows.

This hybrid mechanism – buybacks in the secondary market financed by multilaterals, followed by the issuance of guaranteed bonds – freed up resources for 18 countries, including Mexico as a pioneer in 1989, and transformed opaque bank debt into negotiable instruments, reducing global systemic risk.

However, the comparison with Brady is not total: While that required the issuance of new bonds and bilateral negotiations with hundreds of creditor banks – a process that took years and depended on grants of voluntary forgiveness –, Milei’s maneuver opts for direct buybacks in the secondary market without new issuancetaking advantage of the fragmentation of holders (hedge funds, banks and retail) for more agile execution via JP Morgan.

The similarity lies in the use of multilateral organizations to “relieve” existing debtbut innovation is in the approach: there are no complex collaterals or equity swapsonly a targeted injection to extend maturities and lower country risk, conditional on milestones such as increasing net reserves.

In this sense, it would not be unusual to seek to scale the operation, with partial guarantees from the US Treasury for repurchased bonds or a “Brady 2.0” with selective swaps for other assets.

Key US financial institutions, including JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs, are for now pushing for solid guarantees from the US government to cover the private component of US$20 billion within the total scheme of US$40 billion, a demand that has paused discussions and highlights the prudence of lenders in the face of the volatility inherent in the electoral run-up.

Source: Ambito