Menu

Society: “Pink Tax” – Why women sometimes have to pay more

Categories

Most Read

This supermarket offers great discounts on blenders

October 25, 2025

No Comments

the impact on activity, employment and salaries

October 25, 2025

No Comments

The Government seeks to anchor expectations for the day after the elections

October 25, 2025

No Comments

The Government enters its second stage with the need to undertake key reforms that ensure stability

October 25, 2025

No Comments

Animal disease: Bird flu is spreading – poultry farmers demand protection

October 25, 2025

No Comments

Latest Posts

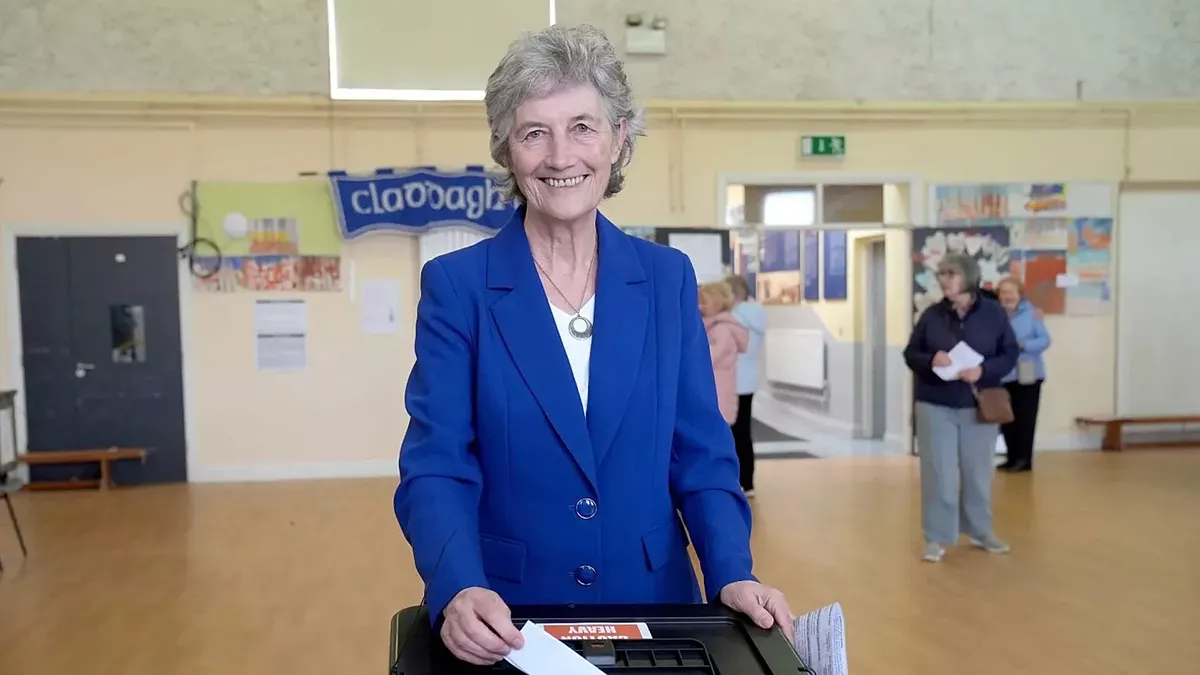

With progressive support, Catherine Connolly is the new president

October 25, 2025

No Comments

October 25, 2025 – 17:07 She obtained more than 63% of the votes and replaces Michael Higgins, who has governed since 2011. She is the

Jérôme Boateng cancels internship at FC Bayern after fan protests

October 25, 2025

No Comments

Internship canceled Jérôme Boateng cancels internship at FC Bayern after fan protests Jérôme Boateng wants to become a coach. That’s why he wants to do

Marco Rubio assured that the US will not rest until Hamas returns the remains of all the hostages murdered in Gaza

October 25, 2025

No Comments

He US Secretary of State, Marco Rubiopromised this Saturday that the remains of all Hamas hostages died in captivity in Loop will return to Israel.

24 Hours Worlds is a comprehensive source of instant world current affairs, offering up-to-the-minute coverage of breaking news and events from around the globe. With a team of experienced journalists and experts on hand 24/7.