“I am convinced that this is the case”he states. “For more than 30 years I have found in abstraction the way to express what I feel.”

The title of the new exhibition is due to the fact that several of the works literally leave the framethey escape their material limits; There are fragments that reach the ceiling, others reach the floor. “It occurred to me to do that with one of the works, it emerged spontaneously, and then I continued with others along the same lines. That’s where the graphic overflow comes from”.

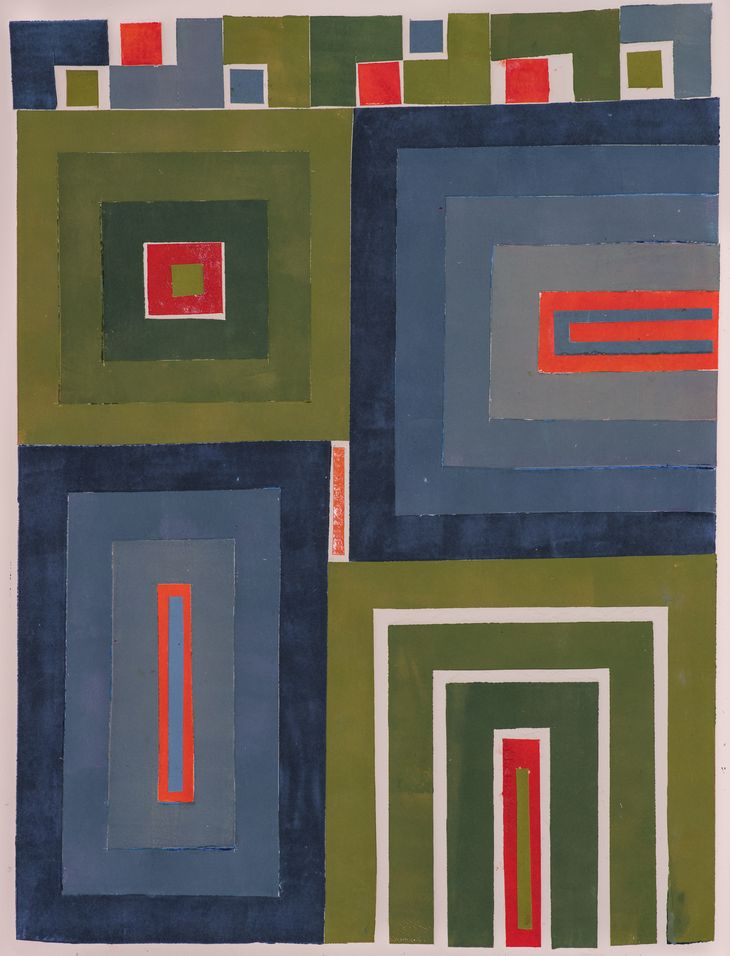

In his curatorial text, Sapollnik writes: “In his work, woodcut is taken to a level of precision where the tool—the gouge—becomes an extension of his hand. Each cut on the surface is a thoughtful decision that builds a geometric universe of circles, triangles, rectangles and polygons that, when intertwined, achieve a subtle and powerful balance. The sharp blade sinks into the matter, causing reasoned tears in search of meaning. This technical rigor, however, is far from cold; On the contrary, Beccaria’s art reveals an emotional charge that transforms its geometry into a rich and evocative visual experience, where color and form interact to convey a variety of moods and emotions.”

Below is a part of the extensive conversation we had with the artist:

Journalist: Is this the first time you have practiced this form of “overflow”?

Horacio Beccaria: In truth, I managed myself in space, although in a different way. I left the plane, the print, and worked with volume, although I am not referring to something sculptural but rather to escape the plane. In that direction, sometimes I come and go. Remember that the 60s were years of a lot of experimentation, my times of the Graphic Art Group.

Q: A way to break the format not only in the content but also in the form.

HB: That’s how it is. And we did many public demonstrations of engraving in the streets, in the squares. We broke the structure of traditional engraving that until then dominated graphic art. Now I have returned, but I also did it at other times in my work. Now I look for an expansion in space: I occupy the staircase, the painting reaches it, I take the walls. The work appropriates the space. It is not planned, the work is taking me.

Q: Was your figurative period completely behind you?

HB: Well, you never know, but I’m not feeling it right now. I feel identified with the geometric. Since the early 90s I embraced abstraction. The grand prize I won at the National Salon was for a figurative triptych, inspired by the work of Dürer. The central part, the human form, had folds of cloth, typical of Dürer. I took that, I enlarged it, and abstract images began to appear, which were the ones I used on both sides of the triptych. So that triptych is only figurative in the center, and abstract on the sides. So it was Dürer who turned me towards abstraction.

that lavished red gold0861.jpg

“Let him lavish red gold”, one of Borges’ lines that gives the title to this work by Beccaria.

Genesis

Q: What is the genesis of your works?

HB: I have no previous sketches, the white paper leads me to what the work will be. I work with a material called high impact, a white surface; With a pencil I draw on the matrix, and I organize the composition without a previous sketch, and then I start to engrave it, to cut the parts. I had a small period, between figuration and the abstract, of about five years, where I worked with a photographic technique called fotoplay, objects created from photographs, but not figurative.

Q: What was that figurative stage like?

HB: The human figure. I started with a series based on old photos, called “The Bride”, located at the beginning of the 20th century. Then I worked more freely, and I did a work called “Ana Tomía’s injury.”

Q.: A play on words with Rembrandt’s famous work, “The Anatomy Lesson.”

HB: Exact. They were three circular objects that represented the female figure seen from different angles, split, hence the injury. But it was never exhibited. It was because of my inexperience at that time, I took it to the National Show, but instead of using firmer cardboard I used ordinary cardboard, and the humidity damaged it. When the jury saw it, it was destroyed.

Q: The idea and title are excellent. It would be a very good idea to rebuild it.

HB: (smiles): Let’s see…

Q: Do you have disciples?

HB: No, by own decision. I retired in 2019 after 50 years of teaching. I taught classes at the Faculty of La Plata, at the UNA, at the School of Fine Arts of Quilmes. The number of students I had is countless. Sometimes I meet, in a meeting, great people, who greet me and tell me that I was their teacher. Of course, I started as a teacher in 1968, in Azul. I grew up, artistically, teaching, but I have no disciples. One of the things that I always imposed on myself was not to try to influence anyone, just to transmit the technique. I tried to rescue the essence of each student and not impose mine on them. There are those who want to do it, that is not my case. I had none other than Fernando López Anaya and Ana María Moncalvo as teachers, and none of them imposed their ways of working on me, and I did the same with my students.

There is no longer a moon that is not a mirror of the past.jpg

“There is no longer a moon that is not a mirror of the past”: another of Jorge Luis Borges’ verses as the title of this work by Beccaria.

The overflow and the prophecy

Q: How is the new exhibition formed?

HB: There are about 36 works, all new, except for two old ones that were never exhibited.

Q: What are those two works?

HB: With one of them I won a prize at the National Hall; It is called “Beccaria for Beccaria”. It is a screen measuring 3 meters, extended, by 1.70 high, and it has to do with my last name in relation to the great Italian jurist of the 18th century, Cesare Beccaria: the upper part refers to him, and the lower part me. I took fragments of his books, and below I made a critique of the time we lived in. That work is from 1973, three years before the military coup. They are texts about atrocity, violence, torture.

Q: Prophetic.

HB: Somehow I got ahead of the facts. The work will be placed at the entrance to the exhibition. The other, from 1995, is one where I went to the total volume of the painting, but without leaving the limits like the current ones. There is relief inside the rectangle.

Q.: You work alone in your workshop in Lanús, your birthplace.

HB: I always did it like that. But not in silence. I need either the radio or listening to music, I can’t work in silence. Maybe this has to do with my youth: I worked at Casa de Moneda, as a draftsman, between 1965 and 1969. I designed lottery tickets. And they worked there in total silence, it seemed like a cloister, or a library. People walked on tiptoe. I suffered a lot from that silence, spending seven hours in front of the desk, no one speaking, just looking at the back of the head of the person in front of us. It ended up being unbearable, which is why the silence prevents me from working.

In another part of his presentation, Sapollnik duck: “In this celebration of form and color, Beccaria inserts himself into a tradition that is reminiscent of the art theories of contemporary figures such as Donald Judd and Frank Stella, for whom geometric art has an expressive intensity that goes beyond representation. . Beccaria, like them, shows us how formal elements can reflect the complexities of human experience without resorting to realistic figures. His work thus challenges conventional notions of representation, providing a dynamism and vitality that connect us with the flow of everyday life.”

Source: Ambito