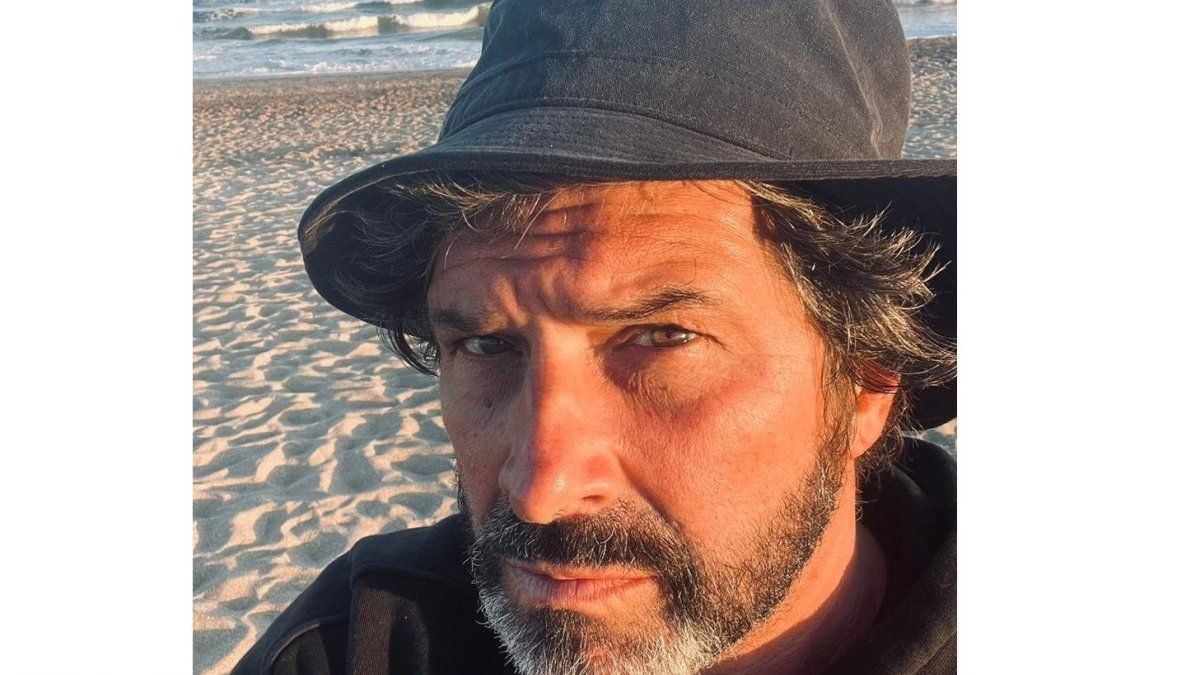

Suddenly life amid popularity is displaced by his father’s terminal disease, and while accompanying him, Iván Noble Start writing “Dr. Álvarez against the All Blacks” (Planet) looking to unveil the father’s enigma. An emotional, moving bet that becomes valuation of life. Iván (Álvarez) Nobleformer student of Sociology, poet, singer, leader of “The knights of burning”film and television actor, has published before “Of such a stick” and “like the crab”, stories. We dialogue with him.

Journalist: Writing about the father’s death to some writers led them to a kind of rediscovery. Something of that happened to him?

Iván Noble: The father-son relationship is like a black box. One believes that he knows his father, but it is not so. One considers that he is the most familiar person of his life, but as he leaves a deep one, he faces a very wide enigma. The father-child relationship is forged unsuspected. I wrote “Dr. Álvarez against the All Blacks” from my old man’s disease. Before, sometimes, I had thought about my relationship with him, but I didn’t have an urgency that led me to review it, until I realized that I was going against the clock.

Q.: His father did not have a fulminating death, that allowed him to have time with him.

In: Within the pain, when we knew that his illness was aggressive and irreversible, I thought he was going to have between twelve and eighteen months and felt that a window was opened to a farewell that had to travel delicately, loving. At that time I did not know that I was going to write about that, but I was taking notes, registering milestones for the chronicle of that time. I think the children’s books about his father, from Kafka to Philip Roth or John Irving, are crossed by a farewell, by the search for a way of saying goodbye.

Q.: With the “heritage” Roth, it has a direct relationship, in both cases the patient father of brain cancer.

In: It is true, but I thought in other cases, very different, such as those lived by Paul Auster or John Fante, and the various ways of narrating a relationship that builds us more than we think. In my case it was a personal exercise that wanted it to be more than an elegy.

Q.: To escape melancholy sought to remember vital moments?

In: In that a friend, the writer Juan José Becerra, had enough responsibility. When I averaged the writing of the book I decided to show it to him. He told me: it excites a lot, but do not talk only about the death of your old man, he also talk about his life, because if you are not going to get too dreary, and you don’t have that record of your old man. From there I was punctuing memories of my childhood that I rescued thanks to writing the book.

Q.: How does that title of your father arise facing “all the black”?

In: People ask how inspiration is, and is anywhere whenever you are alert. In a therapy session, which I was doing by bullshit, my father gets sick and the kiosk of life is immediately accommodated. I talk to my therapist and tell me: you told me that your old man played rugby, this you know, but it is my obligation to tell you, your old man from now on is playing against the All Blacks. It was a powerful image that went to the notebook.

Q.: One of the book features is the typically Argentine scenario.

In: Family of the 70s, of the middle-media class of the Buenos Aires conurbano. In the current vertiginous world some can be unimaginable: La Casita, La Canchita in the field of the factory. It was my village. I tried to paint it. That was a look on that neighborhood, on that country.

Q.: Isn’t there an idealization of that conurbano doctor, in love with his wife and children, slowly and red wine?

In: That was, absolutely. Of course, there are still neighborhood doctors who slip, and so it was. And well, when you travel to your childhood she goes in search of a lost homeland.

Q.: Were there things that helped him write?

In: I didn’t want to tell my old woman who was writing until I finished. I wasn’t sure I could finish. When I was going to see her, she is still in my home house, I checked things about my old man: photos, newspaper clippings when I played chess. Towards a certain personal, family archeology. It was my Magdalena. I wrote with those photos on the desk to see where they took me.

Q.: Was it difficult to close the story?

In: I come from the world of songs and finish them is easier. I did not know if I finished where I was, if I needed a twist, if it should continue. There was important Juan (Becerra). I asked him to be my editor. All he did was point out two or three moments, and tell me: for me it is.

Q.: Upon mentioning Onetti and Vargas Llosa, what others, in addition to Becerra, helped him?

In: It sounds pretentious to talk about authors that I have read, some unsuspecting may think that I am in the same aesthetic universe as them, and that is very difficult, the authors that one reads are incombustible. I really like the American narrative: Hemingway, Carver, Cheever, Fante. Onetti is impressive, his books inherited, among others, of my old people. I hope that the read is fuel for me.

Q.: Do you think “Dr. Álvarez against the All Blacks” will drive him to continue in the world of the novel?

In: It is my intention. I am fifty -seven years old. I already wrote too many songs. I think this book can be, for a long time, expected push.

Source: Ambito

I am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor at a major news website, and my focus is on covering the latest trends in entertainment. I also write occasional pieces for other outlets, and have authored two books about the entertainment industry.