Journalist: How did the idea of reissuing El ultimo punk come about?

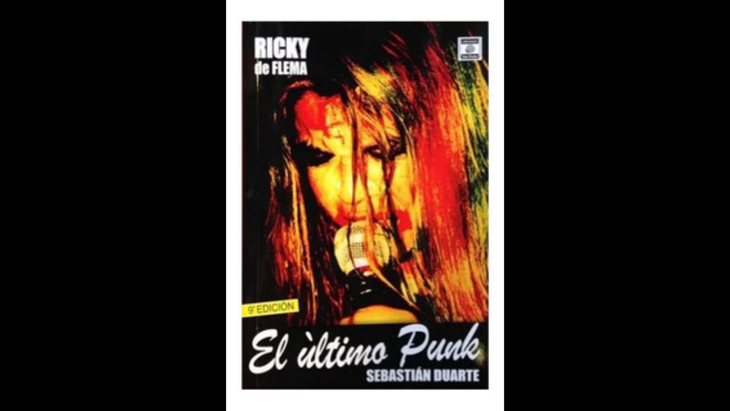

Sebastian Duarte: The artist is magnified because it is two decades since his death. The book is now republished in its actual ninth edition. It has already sold 10,000 copies self-managed. That is something strange, because it was done hand in hand with self-management and independence. I tried to follow the same line as the autograph: the defense of self-management. It just coincides with the 20 years since Ricky’s death. Obviously it is a kind of revisionism of what the artist was, of the canvas that he left and of a scene that is today nurtured by his legacy through his work and his life; of his ideology mainly.

Q.: What prompted you to write about Ricky?

SD: Ricky was a character who became punk to the extent that there began to be a parallelism between the things he did, the information he brought and taking punk seriously, but he came more from heavy metal. That character is the one that caught my attention; he caught my attention from the age of 14, when I met him. He was a very important character in our neighborhood. He was not Charly García, but he was a well-known underground character, who had a lot to do with the streets, the factories, the neighborhood clubs like El Porvenir, the bars and all the street idiosyncrasies of the suburbs. He somehow ended up being a reference for me.

Q.: How was your relationship with him?

SD: Ricky had to do with the region that I was part of. It was hand in hand with my early youth. I met him when I was 14 years old. At that time, in the 1980s, it was not so normal for young people to cross the Pueyrredón bridge or the La Boca bridge. If you were very young, generally everything that happened passed through the area, because your parents didn’t let you cross the bridge either. That scene was very neighborhood, with the rise of punk at the time. First came Los Violadores, but then there was a bump and there was a lot of union between punk and skateboarding and all that movement that first came from the hand of Metallica, who skated and played hard. A hotbed was generated from the capital that splashed in the suburbs. Some kids who had a lot of money, who came from middle-class families in Avellaneda, had a little more access to information, either through relatives and even because their parents traveled and brought them records. Here, in Avellaneda, something was done with greater authenticity; closely related to the idiosyncrasy of the space.

Q.: What spaces did you share with Ricky?

SD: Here we used to get together in Plaza Alsina and Ricky was a well-known character. There was another character who was up there with Ricky, who was called Charly. He was a punk with long, dyed blue hair. He was a bigger character than Ricky in our neighborhood and all the boys had admiration for Charly, who was also known to Ricky. He always walked the street with his backpack, with flyers from his band. Ricky was like that too. He was a kid who attracted attention. In addition, the word spread that he was a great guitarist; that he was a virtuoso and excelled. Flema was founded by a group of middle-class boys from downtown Avellaneda. The gatherings were in Plaza Alsina. Since they didn’t have a guitarist and Ricky was a character who came from Gerli, a humbler area, they called him because of his virtuosity and because he was cool and cool. He was slightly older than them.

Ricky Espinosa book

Q.: How was the transition from Ricky applied at school and with good grades to the punk emblem of Flema?

SD: He was lower middle class. His dad fixed televisions. Gerli is a very working-class area, he was not a kid with money. He even slept next to the front door of his house, in a PH at the end. There he had his bed, which was a kind of sofa. It was not a middle-class house, with a garage and all the balls. He was a stray. He accommodated himself because he was a kid with a lot of mischief and cunning. He was interested in learning, so he established relationships with middle-class kids from Avellaneda. For kids like Ricky or me, the only way to get information was through middle-class kids. And Ricky wasn’t stupid about that. Plus, those older friends who had access also had a knack for buying beer or a whiskey. I wasn’t interested, but that also gives you a chance. It’s a back and forth, because the middle class kid also learned from the working class kid. That is the composition of Phlegm. What happens is that the other guys stepped aside because Ricky got intense. He did not found Flema, but the founders end up leaving and dedicating themselves to making a living. Not Ricky: he continued in his position of being a musician and defending Flema, his band.

Q.: What did Flema mean in Ricky Espinosa’s life?

SD: When the drummer left, the last one left of the first formation, Ricky got so bad that, being at home, he marked the F for Phlegm with a cigarette. It was like sealing what Phlegm was to him. “You go and I’m going to show you what it is,” he said. It was like a blood pact. Shocked by that, the drummer stayed a while longer, but then he ended up going the same way. It was difficult. For something Ricky later looked for young musicians; that made it easier for him to govern the band. that’s an example

.P.: Beyond Ricky’s chaotic side, there was the lucid musician, with a very sharp vision of things. What cultural readings or consumptions did he have?

SD: What Ricky had was extreme lucidity. That is why he had the ability to be able to narrate in four lines things that take us five pages to understand. He analyzed everyday life and transformed it into a song, everything was very personal. Anyone who listens to all the songs of Flema and reads the book will realize that they are more or less the same. Vida Espinosa, his album, is the reflection of the book. I used it to start working on his biography. I studied his songs and began to go behind each one to reconstruct his life. Ricky was a fan of Bukowski, he loved Pigs and Fishes magazine. He had very big concerns. He actually cross-dressed sometimes. I have come to see him in Cement with garters, skirt, painted. He came from the counterculture of the 80s, he was interested in reading, in Artaud, in writers like those. He was not a kid who stayed in Gerli and nothing else, but those who paid him the rags were there. They were his friends, whom he called “the intimates.” He also loved going to the movies, he listened to new music. He was a normal boy, what happens is that what he was able to build was within punk. He was a different.

Q.: Your last interview with him was in December 2001, six months after his death. How did you find him that time compared to the Ricky you met in your teens?

SD: I found him lucid. There was a situation there, which was his girlfriend. The last times I saw him were always together. It just so happened that I had a program with her. When we did the pilot, we did it with Ricky. He was lucid, he was in his house. It was a very intense talk, where he raised his social ideals, his affinity for independence and what contradicted him the subject of multinationals and the great concentrators of power. He had very formed ideas. What happens is that social hypocrisy was not banked, even though he had details in his life. He suffered a lot when there were betrayals or lies. He was very suspicious of what he said was his friend from the start. He took you to the limit to see if you were really sincere. A lot of people stayed away from him because he was so thick. He irritated you. The Flema kids also opened up about it. The bassist said that when the official girlfriend appeared on a tour, in the midst of Ricky’s recovery from drugs and alcohol, they celebrated because they knew that he would be calm then.

Q.: What do you think is Ricky Espinosa’s legacy two decades after his death?

SD: First, sincerity; second, “he do it, you can”. The kid fought and fought, and, despite all the difficulties he had, he came out ahead. He didn’t stay with a no: he defended his songs, his work. I think that is a great lesson. His other legacy is a very native musical style, which is punk Espinosa. There is a local branch of punk that they call punk Espinosa. He wants to say that the guy made such a strong impression that there are kids who have Espinosa-type punk bands. A subgenre appeared within punk and that is a very important legacy. Flema keeps playing, but Flema was Ricky. I’m not saying it in a bad way or because I wanted to upset them, I’m not interested in that, but Ricky was Phlegm. He was a crude characterization. There was a conceptual and real idea; an accomplished concept. He would get on stage and it was Ricky de Flema. He was Phlegm.

Q.: What is your opinion of the book 17 years after its publication? Would you write it differently today?

SD.: No not at all. I always defended him. I have nothing bad to say, because it is an honest book. It’s telling the life of a musician being absolutely objective as a journalist: looking for sources, if there are three or four sources that coincided, it was included, if there are two that were and two that weren’t, it wasn’t included. Find sources, build a story, put myself on the outside. Objectivism in journalism is very difficult. I stepped aside from the emotional part. I did not empathize emotionally with the deceased artist, but I went behind the skinny’s life and it was narrated that way based on reports. I took trains, buses, I spent nights in bars in Gerli. I mean, behind the character. Everything went into the book.

Q.: Why didn’t Ricky’s family participate?

SD: It is a pity that he did not participate. He could have gotten more information. They wanted to at first and then they didn’t, because Mercedes, Ricky’s official girlfriend, didn’t want to. They authorized me, it’s not that they didn’t. I met with them one night, I went to see them at the house, and they told me that they were excited about the idea, they couldn’t imagine it, and they asked me to think about it. After 15 days, since they did not call me, I called them. The father told me “Look, Sebastian, there’s no problem, do it. In the end we’re not going to participate because we’re still suffering a lot from the loss of our son and when we see Mercedes it’s like seeing him.” She didn’t want to, so they told me that they weren’t going to participate but that she should. The initial idea was to do it with the family, but when they told me no, I was convinced that I had to do it anyway. I said I’m going to do it, I’m going to do an unofficial biography. How many unofficial books have we read? I looked for an alternative path and somehow I think I was able to build the story better because I wasn’t affected by thinking “I can put this in and I can’t put this in.”

Q.: How is the life of El Último Punk after this reissue?

SD: I can tell you that he will probably go to the movies. It is very likely that the biographed artist will be transformed into a film. We’re talking. There is a written script, there is a folder. There are great possibilities. It’s all on track; missing a total yes and someone to provide the money. It would somehow be the trilogy: it was a book, it was the play that was made in La Ranchería, when Ricky’s death was 10 years old, and it needs to be a movie.

Source: Ambito

David William is a talented author who has made a name for himself in the world of writing. He is a professional author who writes on a wide range of topics, from general interest to opinion news. David is currently working as a writer at 24 hours worlds where he brings his unique perspective and in-depth research to his articles, making them both informative and engaging.