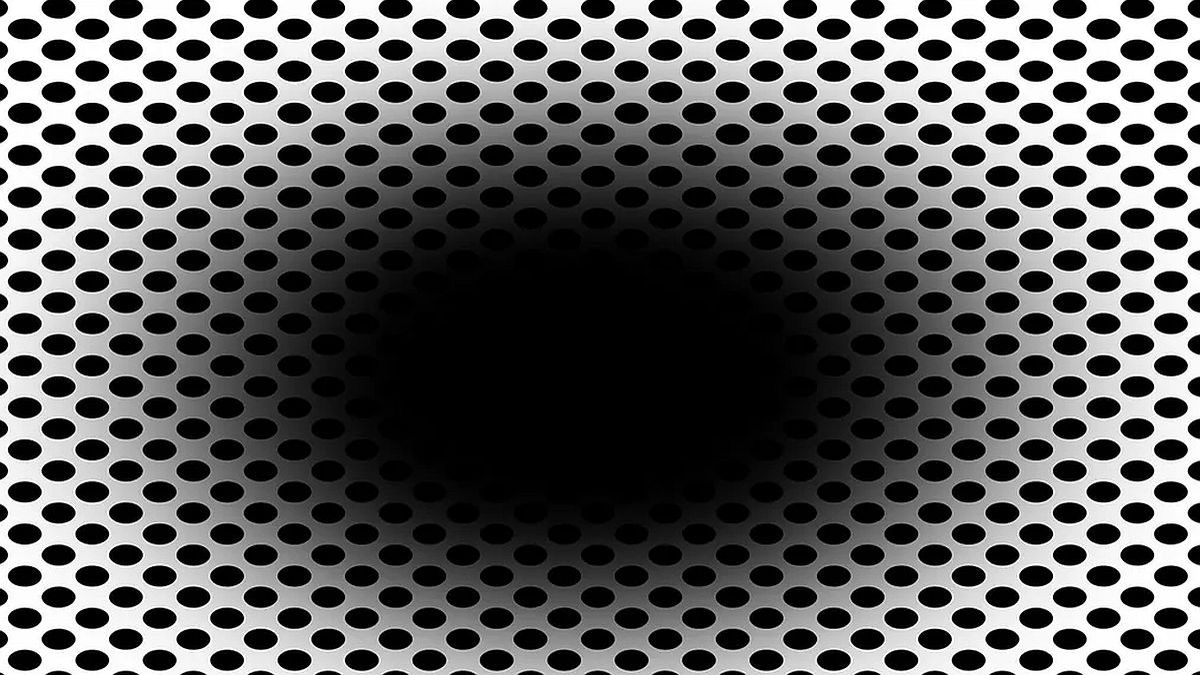

What happens is that, by predicting a change from light to dark, our visual system adjusts very quickly to conditions that it considers potentially dangerous. “Just as glare can dazzle, plunging into the dark is likely risky when navigating in the darkened environment,” the authors write in the post.

They add: “Although, as in any illusion, this expanding virtual darkness is experienced at the cost of veracity, since the observer is not advancing or entering any dark space, this cost is likely to be less severe than if there were no corrections when an observer actually moved into dark space.

But why exactly does the color of the hole and the dots around it affect our mental and physiological responses? To answer this question, the scientists showed different colored “expanding holes” to a group of 50 people with normal vision. They were also taught coded versions of the optical illusion without any discernible pattern of light or color.

What the scientists saw was that the illusionary effect worked best when the hole was black. More specifically, 86% of the participants had the sensation that the darkness was heading towards them when it appeared in this tone.

The scientists tracked the participants’ eye movements and it turned out that their pupils unconsciously dilated when viewing the black hole and contracted only slightly when viewing it white.

“Here we show, based on the new ‘expanding hole’ illusion, that the pupil reacts to the way we perceive light – even if this ‘light’ is imaginary as in the illusion – and not just to the amount of energy light that actually enters the eye,” says psychologist Bruno Laeng of the University of Oslo. “The illusion of the expanding hole causes a corresponding dilation of the pupil, as it would if the darkness actually increased.”

“Our results demonstrate that the pupillary dilation or contraction reflex is not a closed-loop mechanism, like a photocell opening a door, impervious to any information other than the actual amount of light that stimulates the photoreceptor,” he says. Laeng. “Rather, the eye adjusts to perceived and even imagined light, not simply to physical energy.”

The authors have a hypothesis as to why the eye might do this. When the central region is black, our pupils are probably preparing us for a change in luminance in the near future. Rather than seeing information presented directly in front of us, the visual neural network predicts how that information will change in the future, generating “an illusory ‘outward expansion’ of the central ‘hole’ region.”

If the brain didn’t do this, it would take a few milliseconds longer for new visual information to reach higher brain processes. If our pupils took that long to dilate, we wouldn’t be able to navigate the dark as effectively.

Source: Ambito

David William is a talented author who has made a name for himself in the world of writing. He is a professional author who writes on a wide range of topics, from general interest to opinion news. David is currently working as a writer at 24 hours worlds where he brings his unique perspective and in-depth research to his articles, making them both informative and engaging.