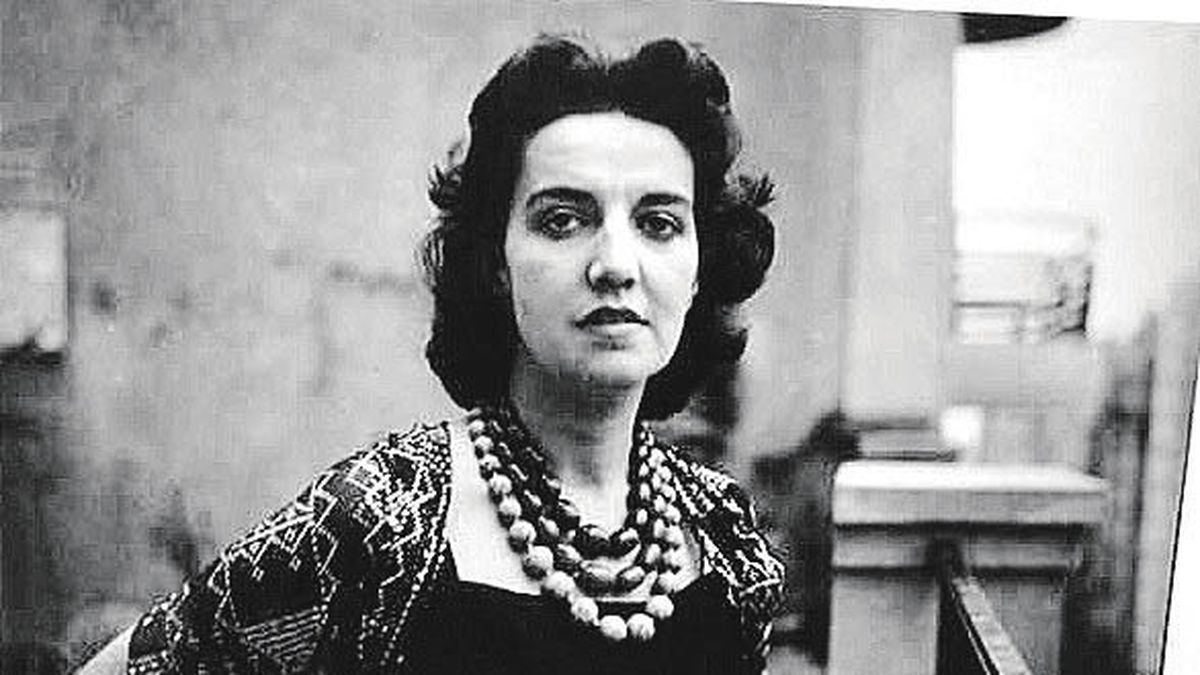

Beatriz Guido, born on December 13, 1922, was the daughter of the architect Ángel Guido, who participated in the Monument to the Flag inaugurated in Rosario in 1957, and of Berta Eirin, a woman with a strong personality who greatly influenced her, and to whom she dedicated the book “A mother”. In tomorrow’s ceremony, she will also declare her “illustrious citizen and distinguished writer” of the city. But, according to what Barney Finn tells this newspaper, the tributes will not end there. For some time, she has been working on the script for a fictional documentary, a docudrama, about Beatriz Guido. which will be produced by Pablo Piedras and Magu Schavelzon. The script received a development grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and Natalia Herrera and Elsa Osorio collaborate with him on its writing. Among her projects, there is also a semi-assembled staging of two unpublished plays by the author, “Waiting for the Castros” and “Las puertas de Oriente”.

A very beautiful text that Barney Finn consecrated to his friend is entitled “Las moradas”, a term that not only resonates those “spiritual dwellings” about which Saint Teresa of Jesus wrote, but also the physical residences, the different houses in which she lived Beatriz Guido, from her birth to her death, which occurred in Madrid, where she was a cultural attaché during part of the government of Raúl Alfonsín, on February 29, 1988. According to Barney, there is no possible distinction between one type of dwelling and another , since “all the houses we inhabit have our footprints and, later, our ghosts. Our houses are ourselves”.

“Beatriz was unstoppable and that’s how I remember her from the day I met her filming ‘La caída’ on Viamonte street, in front of the Faculty”, writes Barney Finn in a passage from “Las moradas”. “Afterward, there were always excuses to see her and be close to filming or private functions, like that night of ‘La caída’ in Alex, or the massive ‘End of the Party’ at the Gran Rex, on a Saturday at 10 in the morning, or in La Plata, with boos, coins, police, gases and final refuge in the Jockey Club, while she, unbeatable and smiling, remained next to ‘Leo the Pompeian’, as she called Torre Nilsson. The ‘Kuki Ant’, as he called her in his letters, knew how to look, watch, suggest, smile; persuasion was one of his gifts, and he used to appear at key moments like the night we stayed at the Tigre Hotel until 7 in the morning. Almost at dawn, Nilsson took his camera along the river and placed it so as not to see it, just a row of trees that were outlined in the night. Beatriz, attentive, followed the instructions that she gave to Lydia Lamaison and Alfredo Alcón until ‘Ecuménico and Natividad’, with their backs to the camera, walked in silence and her son rested her protective hand on his shoulder [La película era “Un guapo del 900”]. She takes it and takes it for granted, but Beatriz tells her something, and Babs proposes a second one that is the same, but with a variant: not supporting her hand, walking together, apart. Beatriz, unable to contain herself, almost like a prank, joined the second, and told me to tell Nilsson about it. Of course no one had an opinion, least of all me, but when the film was screened in private that was the final shot. Betty was always in a corner of the filming writing in her notebook, but watching. Without a doubt, in those days she was an empowered woman, in times where feminism was not present or was not so evident.

Source: Ambito

I am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor at a major news website, and my focus is on covering the latest trends in entertainment. I also write occasional pieces for other outlets, and have authored two books about the entertainment industry.