I am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor at a major news website, and my focus is on covering the latest trends in entertainment. I also write occasional pieces for other outlets, and have authored two books about the entertainment industry.

Menu

Sandra Hülser: She looks calmly at the Oscars

Categories

Most Read

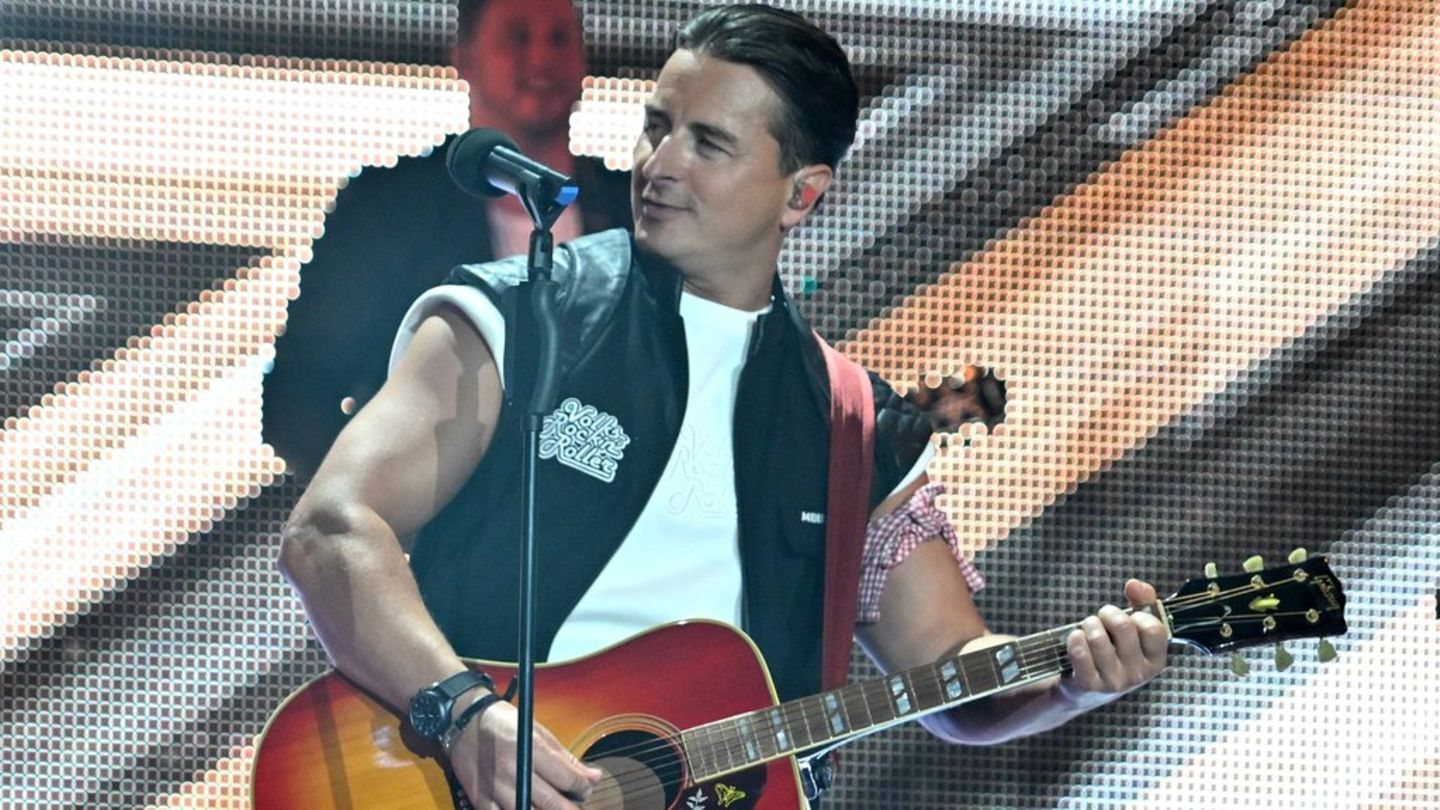

Andreas Gabalier: The singer is taken again

October 12, 2025

No Comments

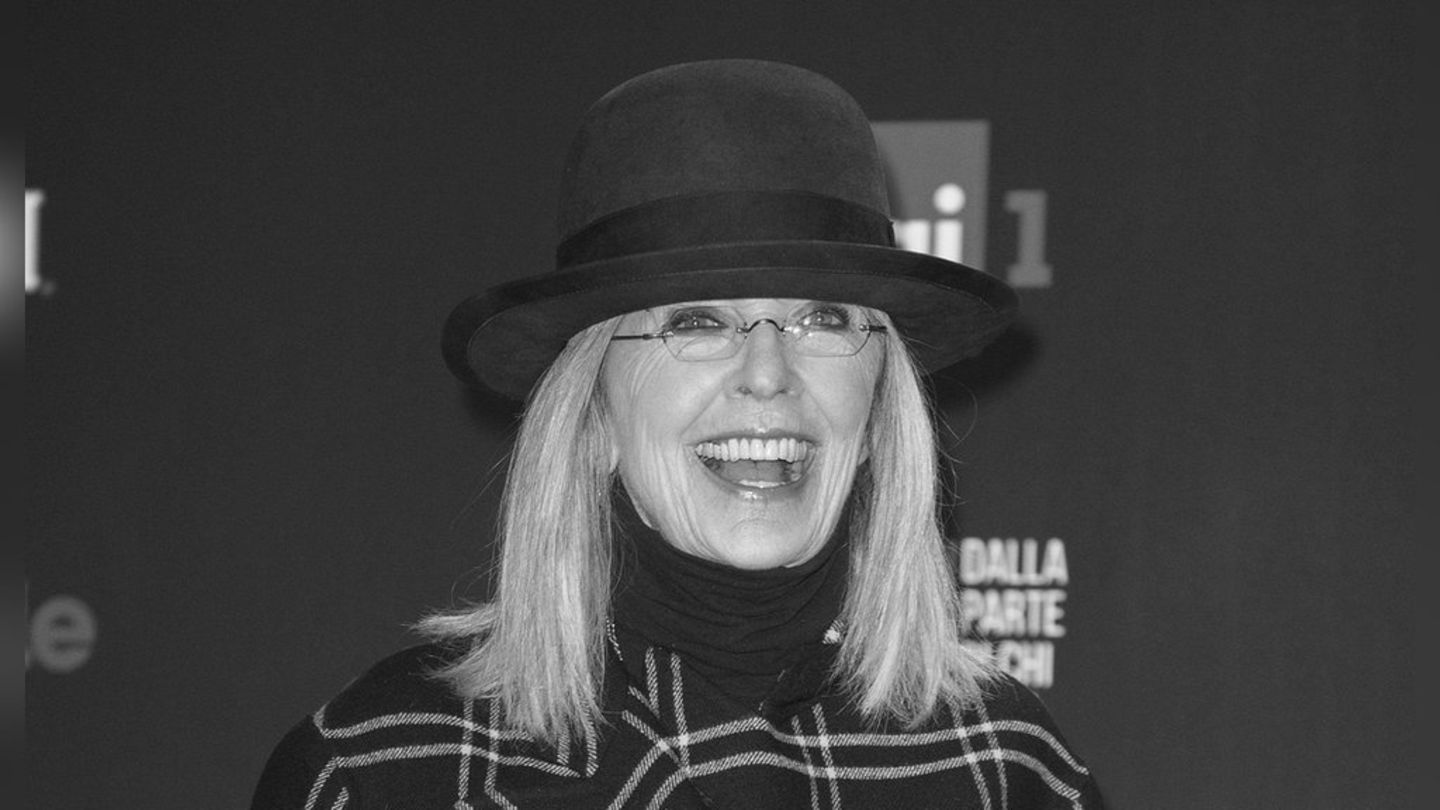

Stars say goodbye to Diane Keaton: She was “unique, brilliant, funny”

October 12, 2025

No Comments

Luciano Pavarotti would have been 90 years old: the legend lives on

October 12, 2025

No Comments

Tips from Monsieur Moissonnier: Cell phones off the table! – This is how you behave in a restaurant

October 12, 2025

No Comments

Oscar winner Diane Keaton is dead: “It was so unexpected”

October 12, 2025

No Comments

Latest Posts

Kevin Njie: Missing reality star has been found

October 12, 2025

No Comments

Lisa HarrisI am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor

Andreas Gabalier: The singer is taken again

October 12, 2025

No Comments

Lisa HarrisI am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor

Stars say goodbye to Diane Keaton: She was “unique, brilliant, funny”

October 12, 2025

No Comments

Lisa HarrisI am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor

24 Hours Worlds is a comprehensive source of instant world current affairs, offering up-to-the-minute coverage of breaking news and events from around the globe. With a team of experienced journalists and experts on hand 24/7.