I am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor at a major news website, and my focus is on covering the latest trends in entertainment. I also write occasional pieces for other outlets, and have authored two books about the entertainment industry.

Menu

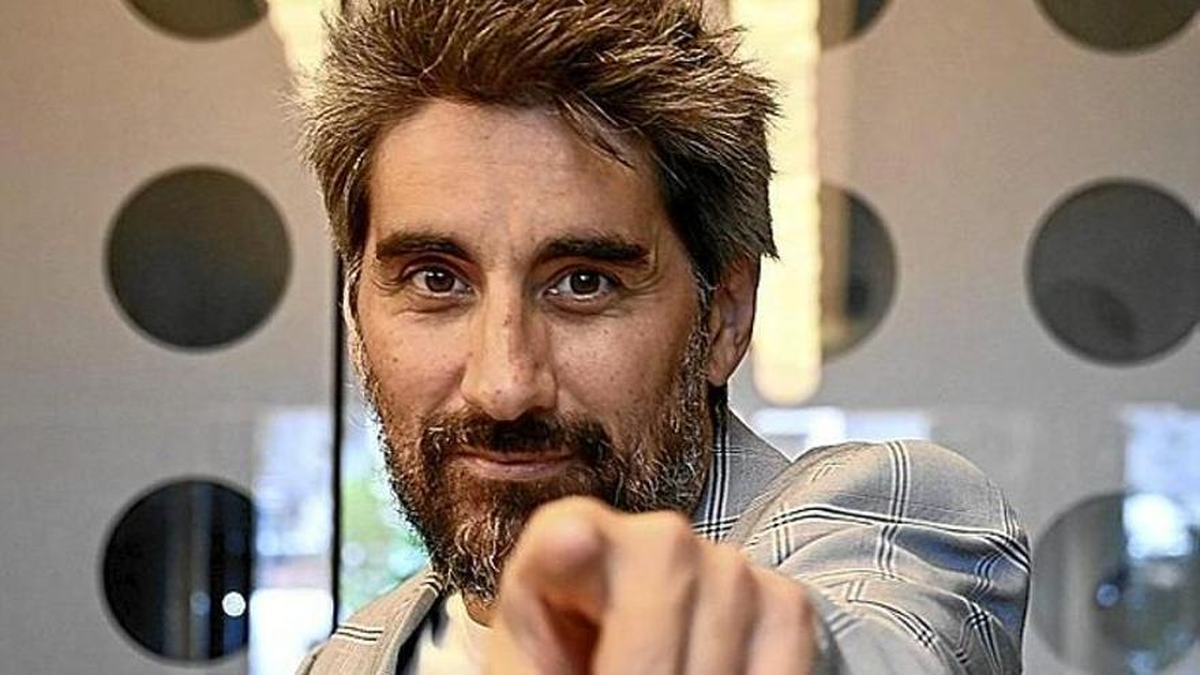

Loureiro: a ruthless chronicle of a small town, a big hell

Categories

Most Read

Bye MTV: 5 iconic moments of the music signal that marked its history

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Ideal for fans of the saga: Netflix released a film that brings together two titans of science fiction

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Bye MTV: its signal will officially be turned off after 44 years of history

October 14, 2025

No Comments

MasterChef Celebrity: how was the rating on the cooking reality show’s return to television

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Latest Posts

The health benefits of intermittent fasting: the cause that can help the body

October 14, 2025

No Comments

October 14, 2025 – 12:52 Thanks to the rise of intermittent fasting as a diet method, many people wonder what benefits it can bring to

Gaza receives more than 190,000 tons of humanitarian aid from the UN after the peace agreement

October 14, 2025

No Comments

October 14, 2025 – 12:34 The UN announces the massive entry of food, medicine and gas, while workers register intense population movements in the Gaza

Time magazine praised Donald Trump, but was outraged by a detail on the cover

October 14, 2025

No Comments

The renowned American publication time dedicated its last cover to President of the United States, Donald Trump, who stood out as one of the main

24 Hours Worlds is a comprehensive source of instant world current affairs, offering up-to-the-minute coverage of breaking news and events from around the globe. With a team of experienced journalists and experts on hand 24/7.