Discovering what motivated her to write, and the way in which she did it, is the starting point of “The shores of the sweet sea” (Edhasa) of Laura Alcobaa work in which the Argentine-French writer reviews the debut work that established her internationally, “The House of Rabbits.” From Paris. where you live. We talk to her.

Journalist: Did you return to “The Rabbit House” because you discovered that there was something you hadn’t told?

Laura Alcoba: Although at the end of the book I evoke the story of “The House of Rabbits,” in “The Shores of the Sweet Sea” I try to put into words how the need to write arose in me. And how writing, time, memory and the body are linked in that impulse and in that decision.

Q: Would you have wanted to talk about that initial motivation with your editor when you summoned her to tell her that they were going to publish your debut work?

THE: I was quoted by Roger Granier, a legendary Gallimard writer and editor who had worked with Albert Camus. It was like Gallimard’s memory. He was retired and was still there. The first thing he told me was that he would have liked to give my book to Héctor Bianciotti, the French-Argentine editor of Gallimard, “but it is there – he pointed to an office – and it is as if it were not there; His body is there, but his mind is not.” Bianciotti went to Gallimard without knowing why he was going. He went, Granier told me, because his body remembered that he was a writer. His body remembered that he had to write, but he no longer had the words. The experience that the body remembers something that one is not aware of, on the contrary, had given me words and prompted me to write.

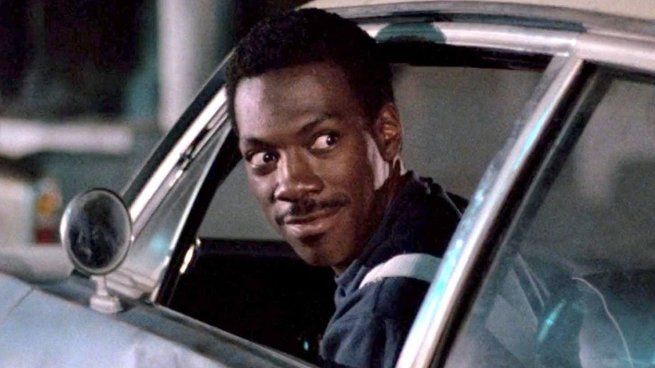

laura alcoba.jpg

MALBA

Q.: You arrived in France when you were ten years old, after having lived with your parents in a Montoneros printing press, disguised as a rabbit selling house.

THE: When in 2003 I visited that place, which had become historic, to be able to pass by the side that hid the printing press, which they called the embute, I crouched down like when I was a little girl. And he didn’t have to, the false wall had been razed by repression. In that bending down, in that unnecessary act, past and present became dizzyingly confused. I knew that in that childish act that I did to move to that ghostly place that did not exist in my conscious memory, my body was speaking. And that memory inscribed in the body demanded words.

Q.: Those that you manage to release in your books and that Bianciotti, in his Alzheimer’s, was sad for not achieving?

THE: Bianciotti looking for a first memory in his book “What the night tells the day” arrives at a small operation in which the doctor, to distract him, makes him look at a painting of a sailor in a small boat in the middle of the sea. Sea, sailor, little boat, were things that he did not know. He notes, “I have known the confusion of naming while ignoring and feeling the sense of panic of being a prisoner within myself for lack of words.” It is like a kind of premonition of his last memory, because at the end of his life he was locked in his body without having words.

Q: Does not having words link you to the trauma experienced in your childhood, not speaking, keeping a secret?

THE: There is an echo in Bianciotti’s silence, and the silence imposed on me, which is released from a memory of the body.

Q.: Why did you choose Bianciotti, and not other Argentines living in France such as Cortázar, Saer, Copi, Berti or Alicia Dujovne Ortiz?

THE: They could be, but I start publishing in Gallimard and there, although I can’t see it, is the ghost of Bianciotti. I found it in Granier’s comments, in data from his travels, from his repeated annotations of a single memory. And I discovered that what he was looking for in his childhood memories, trying to go deeper, had echoes with what prompted me to write “The House of the Rabbits”, “The Blue of the Bees”, “The Dance of the spider”

Q: Why did you put in your book a photo of a stone from the river that turns into a heart in the reflection?

THE: It was the first element of this book. It works poetically. I discovered that stone on a walk along the Aven. It is a stone until it becomes a revelation, a heart, and if it is not captured it disappears. It’s like the movements of memory. There are times when something is revealed and then hidden again. That heart is a crossroads in me.

Q: In what sense?

THE: It indicates the time it takes to learn to understand and tame. It is what is glimpsed sometimes, and then you have to look for it. It rebels without you expecting it. It evokes key things that reveal their meaning in an unexpected moment. The river is there, the water, the banks. This book has two sides. It’s on the side here and on the side there. It is in French and Spanish. In the present and in the past.

Q: How did your dialogue with Annie Arnaux come about?

THE: It all started from my book “Through the Forest”. That I received a letter from him was a surprise. He wrote to me that my book had impacted him. He confessed to me that it was the first of mine that he had read. It was from that moment that we maintained the exchange of letters. Annie Arnaux had not yet been awarded the Nobel, but the Nobel did not stop us from continuing our dialogue. She is a truly admirable writer. It opened a totally new horizon in literature. She was the first who managed to connect literature with sociology in a fruitful, creative, profound way. With his work he did something that has been decisive for the narrative of the second part of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st.

Q: What are you working on now?

TO THE: I’m finishing a book that has to do with a ghost.

Source: Ambito

I am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor at a major news website, and my focus is on covering the latest trends in entertainment. I also write occasional pieces for other outlets, and have authored two books about the entertainment industry.