I am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor at a major news website, and my focus is on covering the latest trends in entertainment. I also write occasional pieces for other outlets, and have authored two books about the entertainment industry.

Menu

“Stladed women”: three scientists without Nobel Prize

Categories

Most Read

D’Angelo: Musician dies after battle with cancer

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Sadness in the world of music: D’Angelo, renowned singer, winner of four Grammy Awards, died

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Nicole Kidman: Will she soon be living in Portugal with her daughters?

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Jorge Drexler returns to Argentina with a very special show: how and where to get tickets

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Latest Posts

Trade conflict: Trump is considering giving up Chinese cooking oil because of the soy problem

October 14, 2025

No Comments

AngelicaI am an author and journalist who has written for 24 Hours World. I specialize in covering the economy and write about topics such as

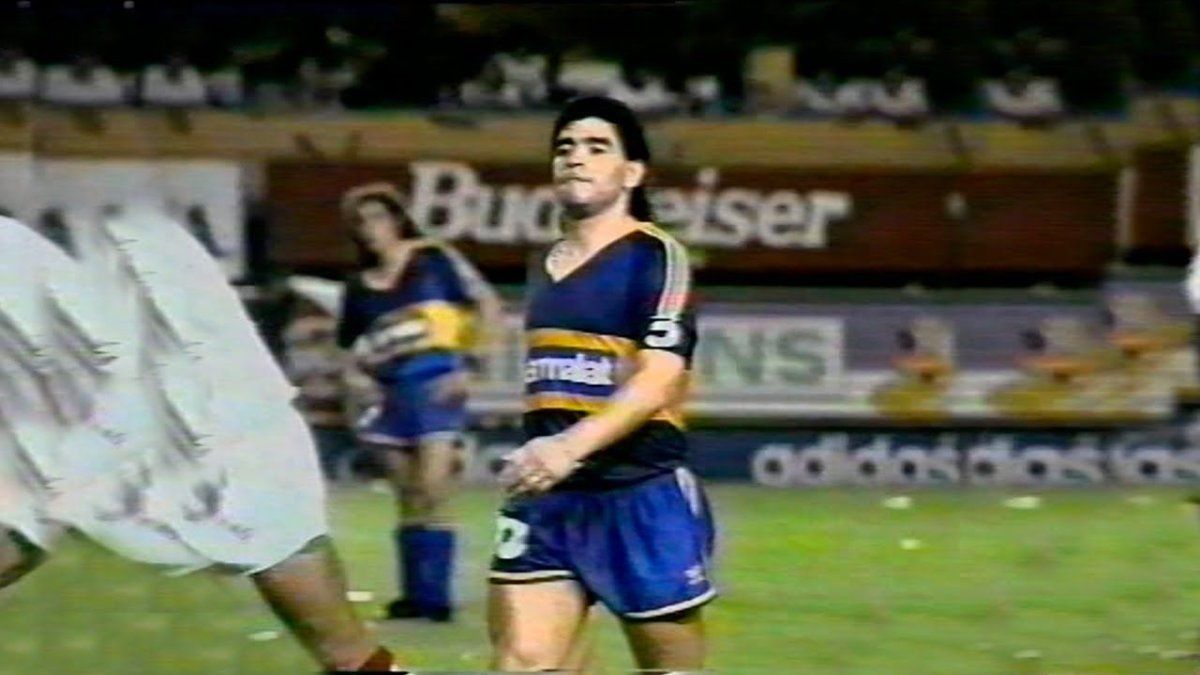

The day Maradona played a match for two different teams: the footballer’s fleeting return to Boca

October 14, 2025

No Comments

October 14, 2025 – 17:30 Pelusa managed to captivate everyone in football and even surprised by playing for two different teams in the same game.

In Ried you can now rent storage space ranging from one to twelve square meters

October 14, 2025

No Comments

Small opening ceremony yesterday with Christoph Wiesner (district manager of the Ried Chamber of Commerce), Stefan Majer (Bauchinger company), Ried’s mayor Bernhard Zwielehner and the

24 Hours Worlds is a comprehensive source of instant world current affairs, offering up-to-the-minute coverage of breaking news and events from around the globe. With a team of experienced journalists and experts on hand 24/7.