ARD documentation

Planet of the viruses: “We got it to do with fear”

Copy the current link

Add to the memorial list

The Ebola virus, Nipah and Sars-Cov-2 have not appeared by chance. The documentary “Spillover” shows how dangerous human interventions can be in nature.

There she stands in her light blue protective suit, in the middle of the night in the forests of Cambodia and is looking for the next deadly pathogen. The infectiologist Jessica Manning carefully frees her prey – bats. You got tangled at your flight through the night in a barely visible network of researchers. With compression sticks, you now carefully take samples from the small animals. For the virus hunters it is the search for the needle in the haystack.

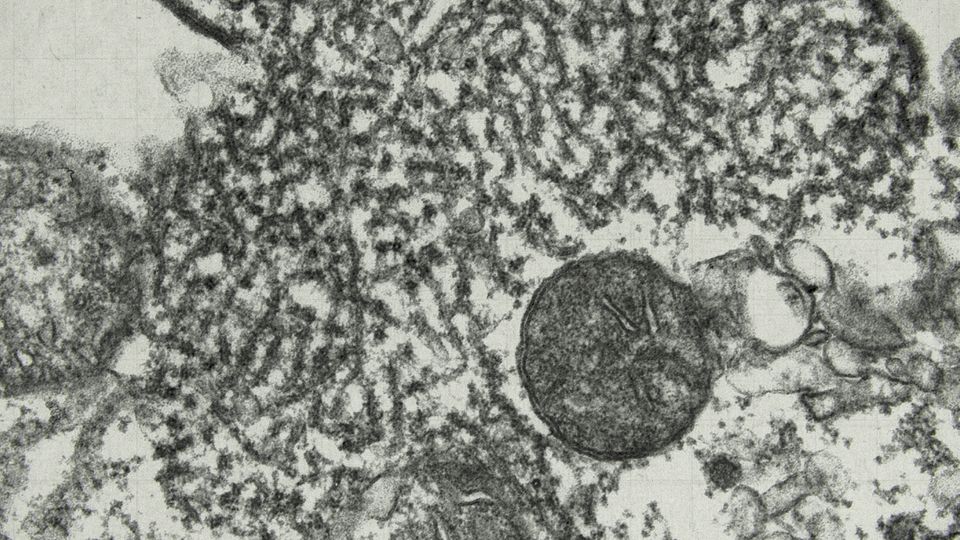

Researchers suspect that there are thousands of undiscovered viruses that have the potential to infect people. For decades, they live unnoticed in a host animal, a flight dog, a mouse or a marten. To this one moment when they suddenly jump to a person. Scientists call this moment Spillover. Even one could trigger a new pandemic. But how does it get? And why is the clocking of these dangerous transfers increasing so dramatically?

“Just as other sweats, they bleeded out of the pores”

The documentary “Spillover – Planet of the Viruses” by director Michael Wech takes the audience on a captivating global journey through time for exactly those locations in which some of the most dangerous viruses made the leap on humans.

Just like in the summer of 1967, when the Behringwerke imported a hundred green sea cats from Africa for their vaccine production. It should be a delivery like many others before. But the monkeys had probably been infected with a new virus during transport at other animals. 29 employees in Marburg infected, seven of them died.

A former biological laboratoryist remembers the cruel thing: “Just as other sweats get sweats, they bled from the pores.” As a spectator, you almost believe in a feature film, but what you see is not a fiction, but also happens.

A new, deadly virus

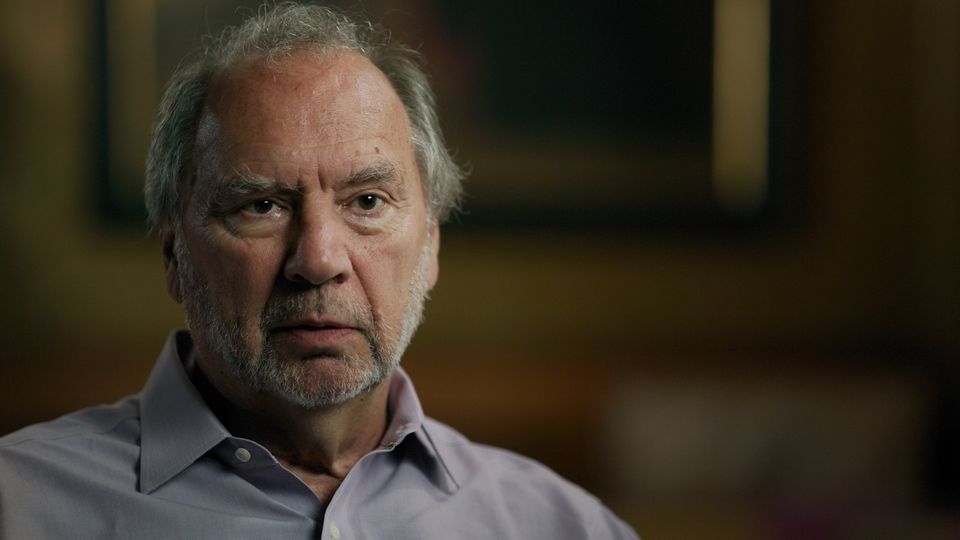

Less than ten years later, a similarly fatal virus jumped to people: “It looked more like spaghetti or worms. The only known virus that looked like this was the Marburg virus. We got it with fear,” says the Belgian-British researcher Peter Piot, who isolated the virus for the first time with colleagues. It was Ebola. In 1993 a new Hanta virus in the Navajo Nation’s reserve in New Mexico killed more than half of the infected. The then still unknown Nipah virus fell victim to about a hundred people in Malaysia in 1999. Further outbreaks followed. And in 2003 Sars showed what a coronavirus is capable of. Less than twenty years later, another coronavirus fell victim to seven million people.

The memories of the researchers involved, their search for the origin of the fatal pathogens and the original recordings from past times are as exciting as a thriller. Every time the researchers ask themselves a question: why right now?

The answer is as simple as uncomfortable: because we make it possible. What reconstruction of the outbreaks-from Marburg to Sars-Cov-2, show his conversations with international experts and the analysis of research without dramatizing that Spillover is not mere coincidences.

Danger for Spillover increases dramatic

We change the ecosystems. We tear the natural protective walls into wild animals and the pathogens that slumber in them. Climate change, for example, drives thousands of animal species into new areas in which their path also crosses that of people. Gigantic areas are cut down for agriculture. In search of protection and food, wild animals also penetrate our habitats.

It was the same with Nipah. At the end of February 1999, a number of young patients, all of pig breeders, died of a painful brain inflammation. Again the cause was a new virus. But where did it come from? In “Spillover”, Malaysian researchers tell how they revealed an exemplary chain reaction in detective work at the time, which began two years earlier in the Indonesia plagued by drought. In 1997, slogans had been cleared out of control, several million hectares of forest had destroyed. Huge swaths of smoke were like an impenetrable veil over large parts of Southeast Asia for months. Flowers and fruits of many trees had been received or had not developed properly. Air dogs that carried the Nipah virus therefore searched for food on mango farms in neighboring Malaysia. They dropped their half -consumed meals. Pigs, devoured the remains. What happened then is history and is still one of the most impressive examples of what consequences our interventions have in nature.

So Wechs Film is not only a captivating documentation, but also a wake -up call. SARS-COV-2, which probably went over to a person on a wild animal market, asked for millions of fatalities. If we continue to exploit the wildlife and destroy our ecosystems, we will have to reckon with a stream of diseases that are transferred by animals to humans in the coming years and decades.

“By 2050, there could be twelve times as many spillover as it is today,” says global change biologist Colin Carlson from Yale University at a point of documentation. “If you continue this trend, what feels quickly today will feel ridiculous compared to what we can expect.”

You can see the documentary by director Michael Wech, a production of Broadview Pictures (producer: Leopold Hoesch), on March 10th at 8:15 p.m. in the first in a 45-minute version and online first in a 90-minute “extended version” in the ARD Mediathek.

Source: Stern

I’m Caroline, a journalist and author for 24 Hours Worlds. I specialize in health-related news and stories, bringing real-world impact to readers across the globe. With my experience in journalism and writing in both print and online formats, I strive to provide reliable information that resonates with audiences from all walks of life.