Like many left-wing voters disappointed with their first term, this consultant in her 40s, who spoke to AFP in Nantes (west), confesses that he will vote for Macron only if his rival in the ballot leads the polls.

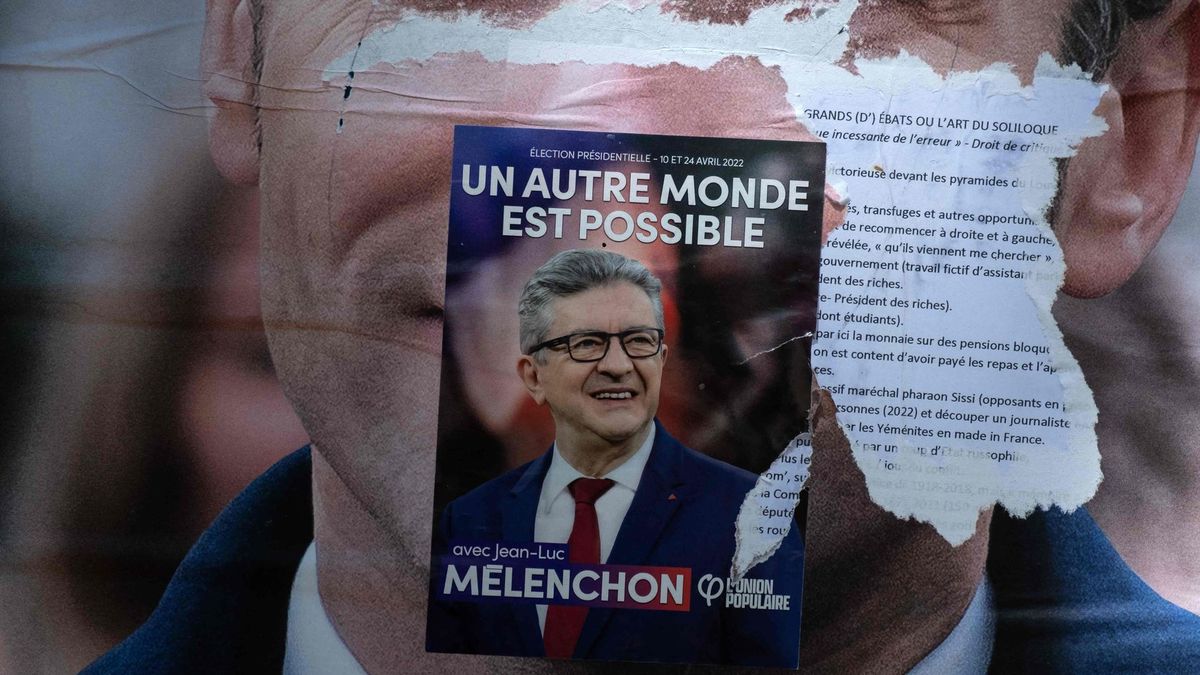

“If they tell us that [Le Pen] can win, we will vote for Macron, but my heart will suffer,” she explains with her husband in this historic socialist bastion, where the leftist candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon won in the first round of the presidential election.

“What he has done is catastrophic. [Macron]has made the poor poorer and the rich richer,” adds Nhili.

Twenty years after the surprising classification of the extreme right for the presidential ballot, the tradition of the “republican front” is no longer what it used to be and the calls to isolate the National Association (RN) have less echo.

The doubts are very notable in the radical wing of the left, in particular among the very courted electorate of Mélenchon, who was left at the gates of the second round, with almost 22% of the vote in the first, on April 10 .

Its voters are the de facto arbiters of the second round. In an internal consultation of his party France Insumisa, the option of the null or blank vote obtained 37.65% of support. A third advocated for Macron and the rest for abstaining. Voting for Marine Le Pen was not contemplated.

This trend is not surprising. In these five years, Macron, elected with the promise of overcoming the division between left and right, has disappointed them and the rejection of him as a person is remarkable.

“I oppose Emmanuel Macron on everything,” says Margot Medkour, leader of the left-wing movement Nantes en Comun. “He is not a bulwark against the extreme right, he has a very authoritarian exercise of power, a very strong contempt for people.”

“Neither banker nor fascist”, reads a wall in the center of Foix, capital of the department of Ariège (south), where Mélenchon (26.07%) was the most voted candidate in the first round, followed by Marine Le Pen ( 23.94%).

“I have heard people say that he will abstain, that Macron will vote to prevent Le Pen’s victory and even that he will vote Le Pen to stop Macron,” explains Gaëtan, a 25-year-old merchant, who also doubts whether to abstain.

On a sunny terrace, three women, very involved in politics, show their different visions for the second round.

“I am anti-fascist. I prefer to introduce a Macron ballot to defeat Le Pen, but then we will have to mobilize in the streets,” says Chloé Dallidet, a 36-year-old social worker.

This former communist councilor talks with Isabelle Loison, a 71-year-old retiree and member of a small Trotskyist party, who will vote invalid, and Dominique Subra, a supporter of Mélenchon, who will vote blank.

The three charge against the “antisocial” policy and the expulsion of migrants by the current president, but also against his controversial phrases, such as when he said to a young man without a job: “I cross the street and I find one (work) for him.”

In this remote department where unemployment is around 9% and poverty was close to 18% in 2019, these statements carry weight. “With the pandemic, there are people who lost their jobs and needed food aid,” recalls Subra, 64.

The expectations of many are now placed on the legislative in France. “It gives me hope that young people and cities have mobilized” in support of Mélenchon, confesses Subra.

Among others, the left reproaches Macron, former banker and former Minister of Economy of former socialist president François Hollande, for reducing housing aid or lower taxes on the wealthiest.

However, Macron can boast of having saved, at least temporarily, the companies and jobs hit by the Covid-19 crisis and of having reduced unemployment.

But left-wing voters do not forget the brutal repression of the demonstrations of the “yellow vests” in 2018 and 2019, a protest against the policy of the current president towards the popular classes.

On the outskirts of Paris, the historic communist “red belt,” the bitterness of leftist voters is also noticeable.

“Everyone here recognized themselves in Mélenchon’s program,” says Azdine Barkaoui, a father of four in the city of Villetaneuse, where Mélenchon won 65% of the vote in the first round.

Many locals are unsure about voting for Macron, as they did en masse in 2017.

Barkaoui is even considering giving his vote to Le Pen, who campaigned on the issue of defending purchasing power and retirement at 60 for certain workers.

The far-right also promised to ban the veil in public spaces, but “we know that she will not be able to implement most of her proposals on Islam,” says this practicing Muslim.

For more than a decade, Le Pen has softened her speech to obscure what her father Jean-Marie LePenfounder of the National Front, which later became the National Association, had built with anti-Semist and racist harangues.

But in essence, the “national priority” will deprive foreigners of various benefits, and his program on immigration has not changed. “It’s like a dish that everyone says is bad, but I want to try it,” says Barkaoui.

Source: Ambito

David William is a talented author who has made a name for himself in the world of writing. He is a professional author who writes on a wide range of topics, from general interest to opinion news. David is currently working as a writer at 24 hours worlds where he brings his unique perspective and in-depth research to his articles, making them both informative and engaging.