White can stand for many things: for innocence, for purity and for order. In gastronomy, white veal has long been considered a sign of quality and a delicacy. Few thought about animal welfare. But they should. Because animal lovers and responsible gourmets will only be happy if the calf is doing well.

In order to be able to judge this, one looks at the path of the calves in advance. A domestic dairy cow gives birth to four calves in her lifetime. The females develop into dairy cows or breeding heifers, which are used abroad to establish milk production. The distance of the male calves is much shorter. They are either slaughtered as a fattening calf at six months old, as a fattening bull or as an ox at a maximum of two years. Or they go abroad. Preferably to Spain or Italy.

70 percent of the veal consumed in Austria, on the other hand, is imported, mostly from the Netherlands, which often has an insane amount of kilometers under its belt and under housing conditions that are more reminiscent of a prison than species-appropriate stables and fresh alpine meadows.

The farmer and the prisoner

“When I look at how animals are kept, I see little difference between prisons and the stables in which pigs, cattle, calves, chickens or geese vegetate,” writes the Lungau organic farmer and butcher Hannes Hönegger in his book “Das goldene Calf. A plea for animal welfare and sustainable agriculture”.

Hönegger knows the dark side of life. He served two and a half years in the high-security wing of Garsten. A tough school, but where he was trained as a butcher and inspired to educate people about quality.

One aspect is the color of the veal. It depends on several factors: breed, sex, blood hemoglobin level, age at slaughter and weight, and feeding. “For some reason, the light meat of the calves is considered to be of particularly high quality and desirable. However, calves with light meat suffer from an iron deficiency, often have too little daylight and are not allowed to graze,” says Hönegger.

If calves were to eat roughage such as hay or grass in addition to their mother’s milk, the calf’s meat would turn red due to the iron content in the feed. This strengthens the immune system. But dark veal is undesirable. That’s why some farms feed their animals milk replacers – an industrial product made from water, palm oil, protein and whey powder. Rearing with real milk, as nature would do, would be too expensive. A fatal calculation for the milkmaid: for the farmer it makes sense to sell the milk to the dairy instead of feeding it to the dairy, but animal welfare and taste are neglected; a highly industrialized agricultural system serves a pronounced consumerism.

white and the price

Hönegger gets angry when he sees the price drop and the animal suffering associated with it. He draws hope from working with allies in the hospitality industry. He supplies six of the eleven best chefs in Austria with his meat. Chefs for whom quality, taste and animal welfare are more important than a bright colour. They are chefs who formed the Koch.Campus association nine years ago and consciously network with farmers and craftsmen in order to further develop quality.

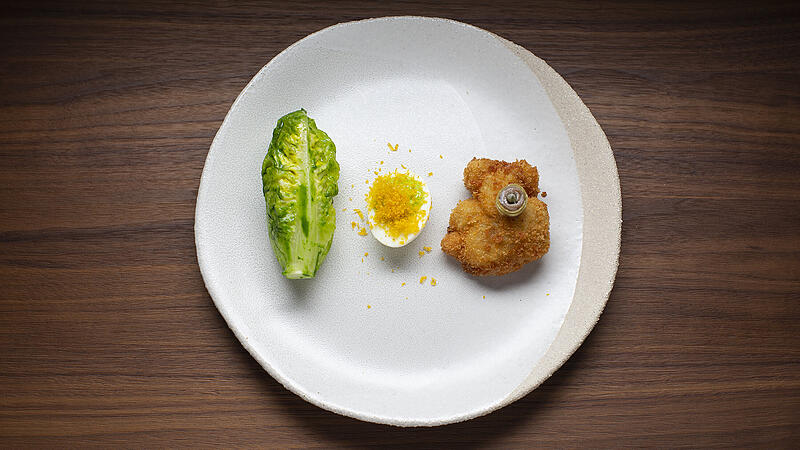

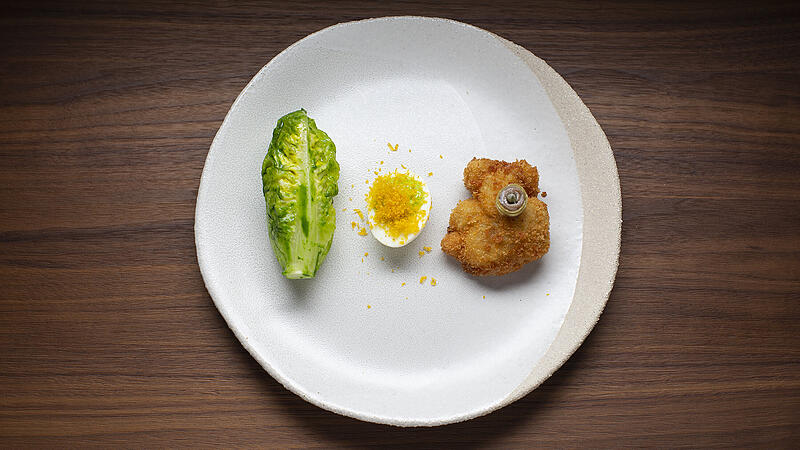

For the grand signeurs of the kitchen, veal consists of more parts than just a schnitzel anyway. They cook sweetbreads and brains just as virtuosically as tow and shoulder. A nose-to-tail philosophy that is the antithesis of the global one-size-fits-all mania. Incidentally, according to Hönegger, 65 percent of the veal ends up in animal carcasses or in dog food, because few cooks are able to use everything and make it tasty for the guest.

Andreas Döllerer is an exception. He is a gifted cook. Of course, he also prompts a veal cutlet in the pan, as only a few can. But Döllerer also knows how to enchant discerning gourmets with baked sweetbreads, roasted veal kidneys or carrots in kidney fat. He has succulent roast kidneys of veal and is considered a feast within his family. “My niece wanted a calf for her wedding,” he says happily. But at the same moment the chef is concerned. “What is currently happening makes me sad. We at Koch.Campus want to do something about it and show other ways that you can go.”

So the association invited 100 responsible gourmets, chefs and producers to Golling and the Wildshut brewery to educate. In a blind tasting, the participants tried nine different tartars and pan-fried dishes and examined the raw legs. Two were from abroad, the rest from Austria, conventional and organic.

In the blind tasting, local organic veal was superior to the others in sensory terms. The Dutch fattened veal, a watery, limp, tasteless but light-colored meat, finished last. For Hönegger, this is confirmation that imported goods of this type cannot keep up in terms of taste. Not even when it comes to animal welfare. Organic is not a trend for him, but should be the long overdue return to normality. Provided it keeps its small structures and doesn’t take on industrial patterns. Because then only the price counts.

“Where the price dictates, it is at the expense of the quality of life, regardless of whether we are talking about chickens, pigs or cattle,” writes Hönegger. It’s the price of white meat.

Book tip: The Lungau organic farmer and butcher Hannes Hönegger tells a gripping story of how he made it from a convict to a model farmer and how he treats the calf with respect. Many recipes “from nose to tail”. Hannes Hönegger: “The Golden Calf”, Brandstätter Verlag, 208 pages, 35 euros

Source: Nachrichten