The possibility that Uruguay have its first president, the search for modifications in the gender violence law, the political parity law truncated in the Senate made some issues related to the feminism and a gender agenda, although without managing to place them as priorities. Focused on macroeconomic and security issues, public policies aimed at a more egalitarian society between women and men went to, at least, a secondary level.

In interview with Ambit, the feminist journalist, member of the Independent Party (PI) and director of National Women’s Institute (InMujeres), Mónica Botterospoke about the present of the gender agenda in the electoral debate, as well as about the recent modifications proposed by the Executive power to the gender violence law.

– Actually, I do not see the agenda as such very present either in the parties that make up the government coalition or in the opposition, no specific proposals have been debated in the government programs.

What is the reason for this absence?

– My interpretation is that this is a very delicate and controversial issue even within the parties, even within the left, that they are trying to, perhaps, postpone until after the internal elections because, in some way, the main candidates are looking for great consensus and this is an issue that breaks waters in all parties. There are sectors of women that pull to one side and sectors that could be identified with more conservative, even reactionary, positions that seek to discredit the gender agenda, for example, calling it “gender ideology” or talking about supposed legal privileges for women.

After the internal ones, could this be reversed or do previous experiences indicate otherwise?

– I don’t see any candidate, much less a party, that raises the flag of the gender agenda. It is not a central issue that usually arises in the campaign, in this case I think it will also depend on the support that the two main female candidates have, Laura Raffo of the National Party and Carolina Cosse of the Broad Front. If the two of them conquer positions, win the internal elections of their parties or achieve a good score, that will probably help put the gender agenda a little more on the table.

But in Uruguay There is still weakness in terms of female political leaders, first, and who also claim the gender agenda, with the great exception of the current vice president of the Republic, Beatriz Argimon, which is feminist. She points out that this has never been central in electoral campaigns and I don’t think it will be central in this one either, despite the fact that both Cosse and Raffo call themselves feminists.

In recent weeks there have been two particular situations: the rejection in the Senate of the parity law and the presentation of modifications to the gender violence law. What reading do you make of both questions?

– They are two different things. The Senate’s rejection of the parity law is not a setback, but rather it never got there. In Uruguay, affirmative actions are traditionally frowned upon, they are always seen as an imposition and a curtailment of freedoms. So it is very difficult, but it must also be said that feminist movements have not traditionally raised the flag of parity, but rather It has been a demand of some political women committed to the gender agenda. It is a terrain to conquer, and it is true that there was no support from some sectors of the government, but it is a process and we are going to go there, without a doubt.

And regarding the gender violence law?

– Perhaps the violence law was a little ambitious and in some procedural aspects it went too far ahead of what we were prepared for. The multi-subject courts were not able to be implemented, so a series of situations arose that made certain sectors see that the guarantees of due process were not given to men. This is very controversial and, of course, the most active groups on the issue of violence see it as a setback. I really see it with concern.

Women 8M march

Photo: Bitter mate/ Meri Parrado

What are the points that concern you?

– An emphasis is added to the law on criminalization of false testimony, of the false complaint, which is already in the Uruguayan legal system, but is placed here with the specific intention of discouraging those who may think of making false complaints. It is alleged that many women, because they are angry or want to harm the man, are making false reports. The reality is that there is no official or unofficial data on what causes this. There is data on women who are victims of violence. At the Women’s Institute we serve more than 3,500 a year, some at imminent risk of life.

I am also afraid that this specific emphasis on false reporting will make many women inhibit themselves from reporting for fear that they may later be accused of false testimony. Women’s movements have spent decades convincing women victims of violence to report it because there will be a State that will believe them and that will give them a response; and this seems a little contradictory about that message.

Why do you think the project is being shipped at this particular time?

– Throughout this period there were complaints from sectors close to the government party and within the government coalition, concerned about the “excesses” of the law of violence. I suppose that with this proposal the president wanted to respond to those questions.

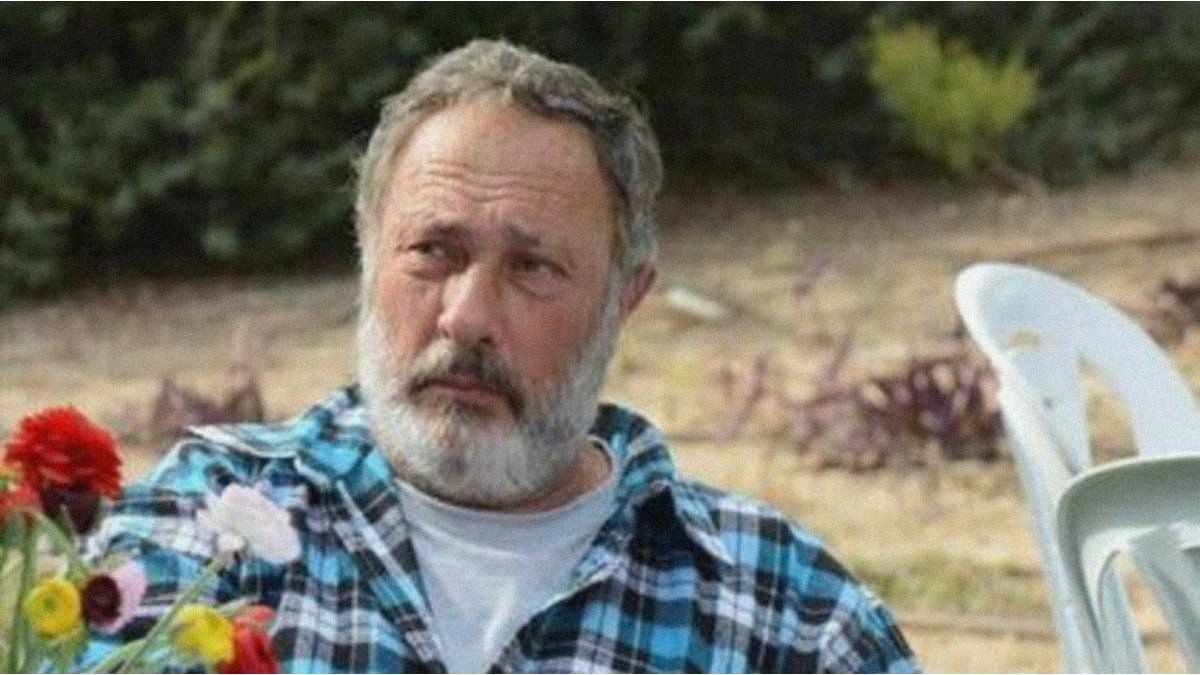

Could the false complaint against Yamandú Orsi and its repercussions on public opinion have influenced him to present it now?

Yes, definitely. There are situations that are triggers and create climates of acceptance of certain proposals.

What are the pending issues that Uruguay has regarding gender issues and that must be resolved in the coming years?

– On the one hand, continue improving the response system for gender violence: provide the Justice Department with more tools, install multi-matter courts, and better finance the violence care model that we offer from InMujeres. Because although we have been improving it, new challenges have arisen in recent years linked to other types of gender violence. It should be modernized; more resources are needed to also optimize the response in psychosocial and legal care for men. In addition, the National Women’s Institute should raise its institutional rank. Today we are a direction that is part of a ministry, and by presiding over the National Gender Council it should have greater autonomy. It could be an autonomous entity, a decentralized body, at least.

And it is important to work on female leadership, because for the gender agenda to be a priority agenda there must be women driving it, otherwise it will be very difficult for issues such as care, gender violence and perspective to be considered top-notch. gender in all aspects of public policy generation.

Source: Ambito