This reciprocal intolerance forced his parents to emigrate to the United States. She was 23 years old.

Marine by vocation, for more than 10 years, he traveled the coasts of America and Europe as a crew member.

Years later, already captain of his own ship, on one of his many voyages across the Atlantic, he was seized by a French warship and imprisoned as a prisoner of war.

At the time he managed to escape. Years later, he returned to England. There he got married and with his wife they arrived at the Río de la Plata, settling in Montevideo. He ran the year 1809.

I was 32 years old. The May Revolution was approaching.

Shortly after his arrival, he was able to acquire his own ship, dedicating himself to the transport of merchandise.

Although not yet intervening, he was one of the silent witnesses, who simply witnessed initially, the events of May 1810.

In 1811, upon returning from one of his trips as a carrier, he decided to settle in Buenos Aires. He was already 34 years old.

A true professional sailor, his task consisted, as I have already stated, in the transport of passengers and merchandise, preferably between the ports of Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

His work allowed him to delve into the secrets of navigation, in the widest river in the world. At the same time he struck up a certain friendship with the most significant figures of the time.

Little by little he identified himself with the ideal of the men who fought for American independence. And he understood that “just as there are men who kill to impose ideas, there are others who would die to defend them.”

He felt in his spirit that a single shoot of justice justified plowing a desert.

Almost without realizing it, he had become the obligatory messenger for the transfer of people and secret revolutionary messages. In addition, he often accompanied the emissaries of the First Board.

Just after the triumphant May Revolution, the formation of a naval force to confront the royalist power became essential.

Juan Larrea, a member of the First Board, did not hesitate to commission him to create the new squad.

And here began, in reality, for us, the endearing story of this sober, long-suffering and fervent Irishman.

Almost without means, he built a fleet with the same dedication that an artist models the clay of his work.

He had to face two terrible war conflicts. The first, against the Spanish, to achieve national independence; and later, against the expansive action of the empire of Brazil. He did it with little boats that looked like toys in front of the tremendous strength of two of the most powerful squads of the time.

Despite this circumstance, he did not mind returning to active life to stop, even, the threat of Franco-British ambitions, when both countries, allies, invaded the waters of the River Plate.

He understood that invasion as arbitrary. And he was not wrong. And Brown, like any worthy man, was measured in the face of weakness, but very strong in the face of force or arbitrariness.

He was able, like all superior men, to fight tenaciously for the seemingly impossible. Until making it… possible.

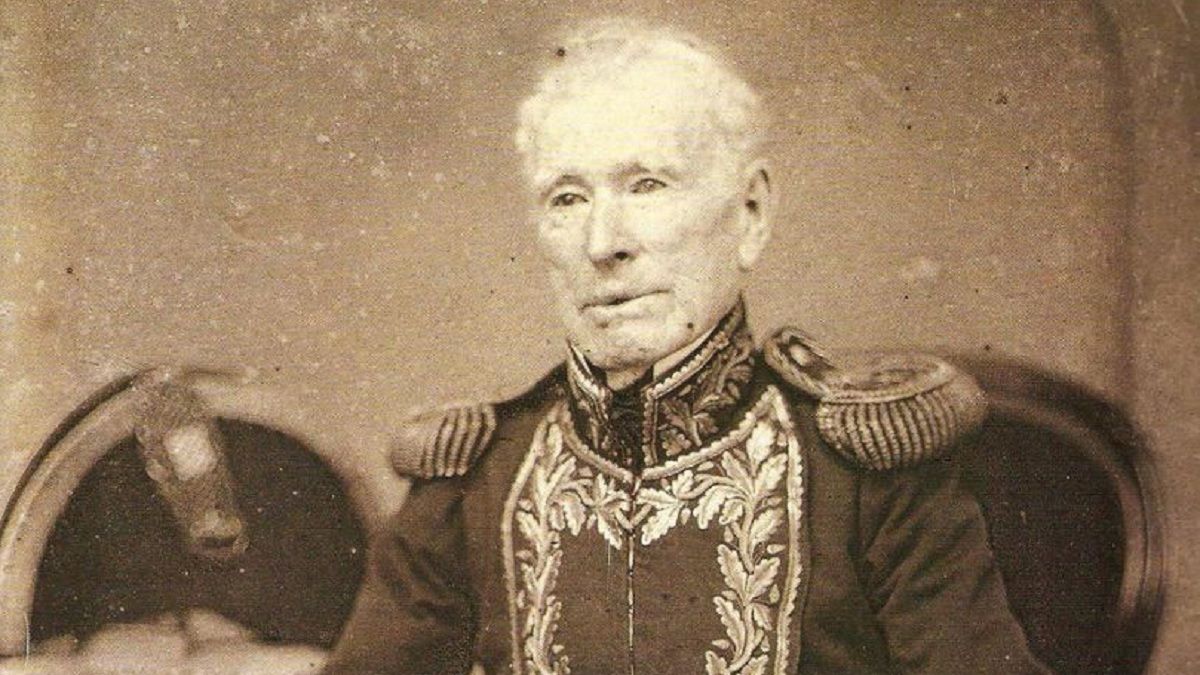

Admiral Guillermo Brown died when he was a little over three months short of his eightieth birthday, on March 3, 1857.

His spiritual need to support the ideals of other men, sentiments that he understood to be fair, brought this aphorism to mind; “There are those who kill to impose ideas. But there are those who die to defend them.”

Source: Ambito