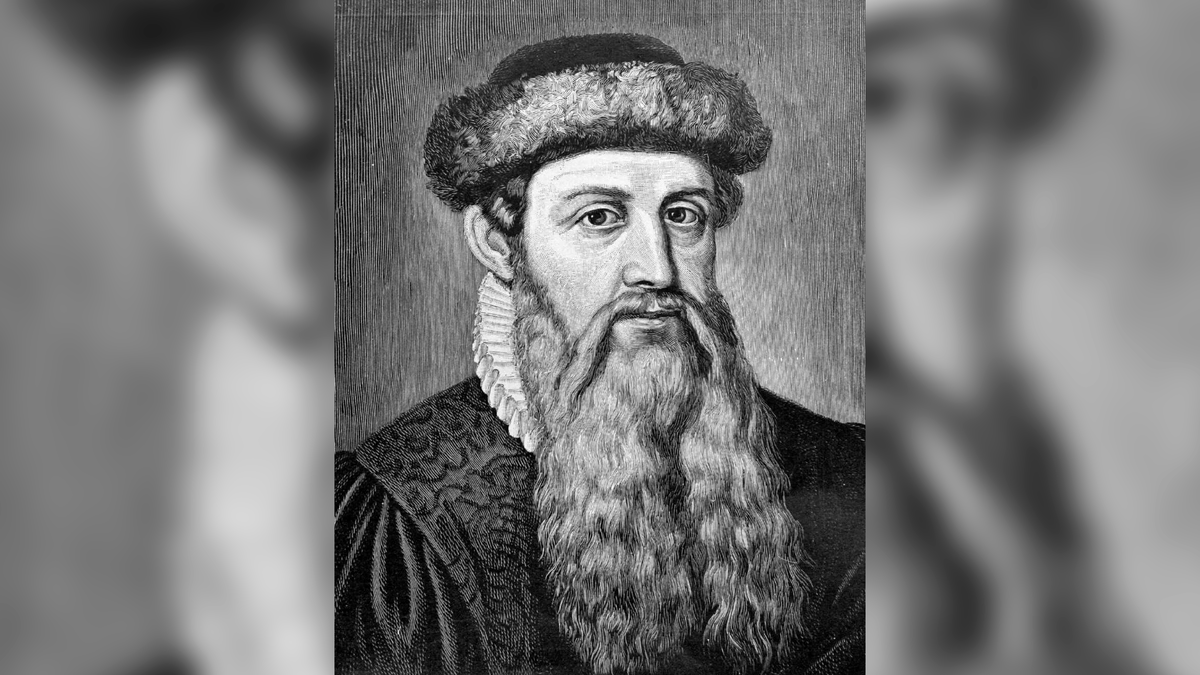

But there is another inventor, a German, born in Mainz, of no less talent than those named, and who undoubtedly advanced the world. Perhaps more than all the mentioned inventors combined. His name was John Gutenberg and he was born in 1398, some 120 years before the discovery of America.

He was initially a skilled goldsmith.

What did this gentleman invent?

Well, nothing less than the printing press. Until then the books were written by hand, one by one, obviously. They required long hours of work and were as rare and coveted as jewels.

Gutenberg created a printing system that used individual characters for each letter to form words, thus opening up the possibility of reproducing a work in a large number of copies, all identical.

As a consequence, the diffusion of ideas and knowledge ceased to be the patrimony of an elite.

After a few essays his first works were two complete editions of the Bible in Latin.

The inventor worked in secret and was always short of money, which is why he was persecuted many times by his creditors, one of whom, with whom he had a debt, appropriated Gutenberg’s invention in exchange for money he owed.

Always on the brink of poverty, Gutenberg was only recognized when he received a pension from the Archbishop of Mainz in 1465.

But the peace did not last long. He died three years later of an unknown disease. In time, the remains of him disappeared.

The first copies printed in the new system, which have survived for five centuries, are called incunabula and are today of extraordinary value.

The books that appeared until December 30, 1500 constitute jewels –in the artistic sense and for their monetary value-.

Connoisseurs estimated that in the initial half century no more than 13,000 titles had been printed.

During the intervening five centuries there were so many reasons for destruction that even that small number seems surprisingly large: deterioration of paper or parchment; catastrophes, wars, fires, floods or shipwrecks, food for rodents, termites or other animals.

The largest collections of incunabula are in the National Library in Paris, the British Museum in London, the Library of Congress in Washington, and the Vatican Library.

Wooden, and later metal, movable type had already been invented in Korea and China, but had not achieved the same impact.

Perhaps because writing systems had thousands of different characters.

The radical novelty with Gutenberg resides in the association of movable types for the composition of the text.

And the use of the printing press, non-existent in Asian societies, leading to printing on sheets of paper.

The aim of the inventor of the printing press, extremely difficult both from a technical and aesthetic point of view, was to mechanically reproduce the letters used in manuscripts.

The “patterns” of the letters were cut from small steel rods and the dies made in this way were impressed in some soft metal.

The types produced lined up, forming sentences. Covered in ink, they printed the text on sheets of paper, placed on a press.

This is how the first printed texts came out in Gutenberg’s workshop.

The printing press as rationalized by Gutenberg was able to expand in Europe and respond to an ever-widening demand for books, at a time of the establishment of universities and the growth of cities, despite social restrictions on cultural access.

More than five and a half centuries have passed since the death of John Gutenberg. But his valuable invention, the printing press, lives on. And we intuit that it will continue for the future of time.

And an aphorism for John Gutenberg:

“Everyone walked. But few left traces.

Source: Ambito

David William is a talented author who has made a name for himself in the world of writing. He is a professional author who writes on a wide range of topics, from general interest to opinion news. David is currently working as a writer at 24 hours worlds where he brings his unique perspective and in-depth research to his articles, making them both informative and engaging.