In the dynamics of this collapse of a government there is a dimension that must be studied further, which is the role played by the community of experts in economics. Economists have been the true architects and carriers of the dominant ideology during those years. In this community of experts there was a very widespread, hegemonic and immovable consensus on the economic policies that Argentina had to adopt at that time. Therefore, to better understand what happened, it is necessary to deepen our knowledge of this network of influential personalities.

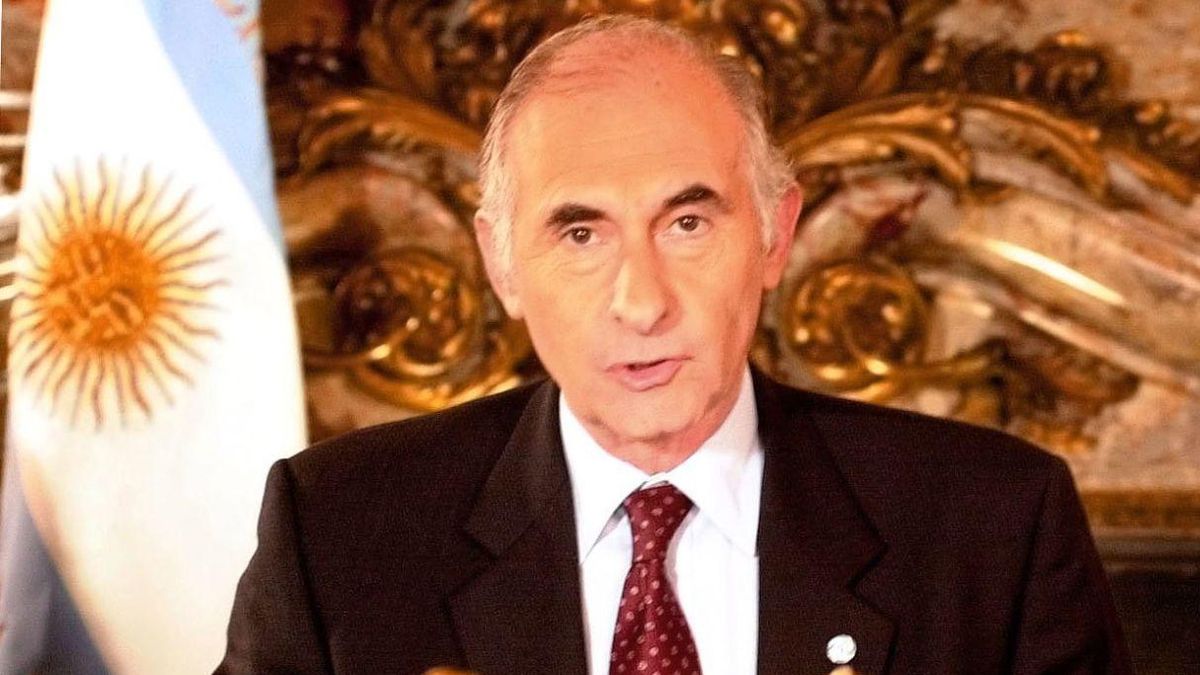

Financial dominance over politics had a lot to do with these key individuals of that period. And it was not a phenomenon limited to Argentina. The decade of the 1990s, characterized by the Washington Consensus and neoliberal economic reforms in various countries of the world, was the decade of technocratic politicians. OR technopols, as Jorge Domínguez (1997) called them. And the key Argentine technopol was Domingo Cavallo. This economist with a doctorate from Harvard University and one of the best known professionals in Argentine economics, was fundamental in this community of experts.

We will call it “technocratic elite”, following the classic of Robert Putnam (1977). The technocracy or “government of the technicians”, defined by Putnam, is characterized by certain beliefs and convictions. Technocrats believe that technique and rational planning must replace the politics of negotiations, endorsements, and concessions. That the technocrat must define his own role, and be free from political commitments.

They believe that progress or the good sought is achieved through depoliticization, and they distrust the values, ideologies and logic of party politics. The State, in the technocratic mindset, is an implementer of public policies that must be placed above social interests.

The employment index in Greater Buenos Aires accentuated the drop in 2001, with small and medium-sized enterprises and the construction sector being the most affected. Additionally, the expectations of employers regarding increasing staff were discouraging, which, added to the deterioration of real indicators, led us to foresee further declines in employment in the coming months.

Although in year-on-year terms there had been an incessant decline, the acceleration of the negative trend in the months of July and August in the three most important conglomerates in the country was remarkable: GBA: (-1.7% y / y in July), (- 3.0% YoY in August); Greater Córdoba: (-2.9% y / y in July), (-3.4% y / y in August); Gran Rosario: (-0.8% y / y in July), (-1.1% y / y in August). To all this, the financial crisis that the economy was going through kept interest rates high and made it harder for SMEs to access credit. But the neoliberal technocracy does not register these issues.

Various works have investigated the modalities of technocracy in Latin American politics. And that leads us to better understand the 2001 crisis. The Argentine case showed the limits of technocratic politicians. The absence of a political foundation for economic policy decisions further weakened an already weak government, and led the president to collapse; the solution to the crisis, later, did not come from the technocracy but from the reconstitution of politics and its institutions.

The question is: why, in a context of political crisis and economic vulnerability, did President De la Rúa believe that technocratization could constitute a way out? That faith in technocratic politics was part of an era, which the escalation of the crisis helped to close: after the Argentine crisis, technocratic politicians would regress in much of the world.

THEY WERE FASHION IN THE NINTIES

We will deal with characterizing the technocratic politician from some paradigmatic cases in countries with similar characteristics: political transition, regime change, and economic reform. Domingo Felipe Cavallo was, in our country, the representative of this line of technocrats specialized in neoliberal reforms in the so-called “emerging markets”.

Although the list is not exhaustive, and is based on references and mentions in different texts in this regard, we selected a set of thirteen personalities (Cavallo, Aspe, Salinas de Gortari, Zedillo, Gaidar, Lee, Singh, Ozal, Cardoso, Kandir, Malan, Bacha, Franco) from seven countries (Argentina, Mexico, Russia, Taiwan, India, Turkey, Brazil) to describe the profile of the technopol or technocratic politician of the 90s. It is, in fact, a much more widespread phenomenon than this group of illustrative cases: a good part of the countries of the planet knew these types of leaders.

The trajectories of the thirteen selected cases – all male, it should be noted – had many points in common. All of them became known as economists, and all but two had postgraduate and doctorate degrees from prestigious economics schools; the two exceptions were Ozal and Cardoso, who came from other academic backgrounds (one an engineer, the other a sociologist and political scientist), but practiced the economics profession anyway. And all of them built their government careers from having held important positions of public function in economic areas. Several of them (Salinas, Zedillo, Lee, Singh, Ozal, Cardoso) were presidents of their countries after having handled economic policy as technicians; Cavallo and Aspe wanted to be, but luck was not with them. It will continue tomorrow.

Professor of Postgraduate UBA and Master’s degrees in private universities. Master in International Economic Policy, Doctor in Political Science, author of 6 books. @PabloTigani

Source From: Ambito