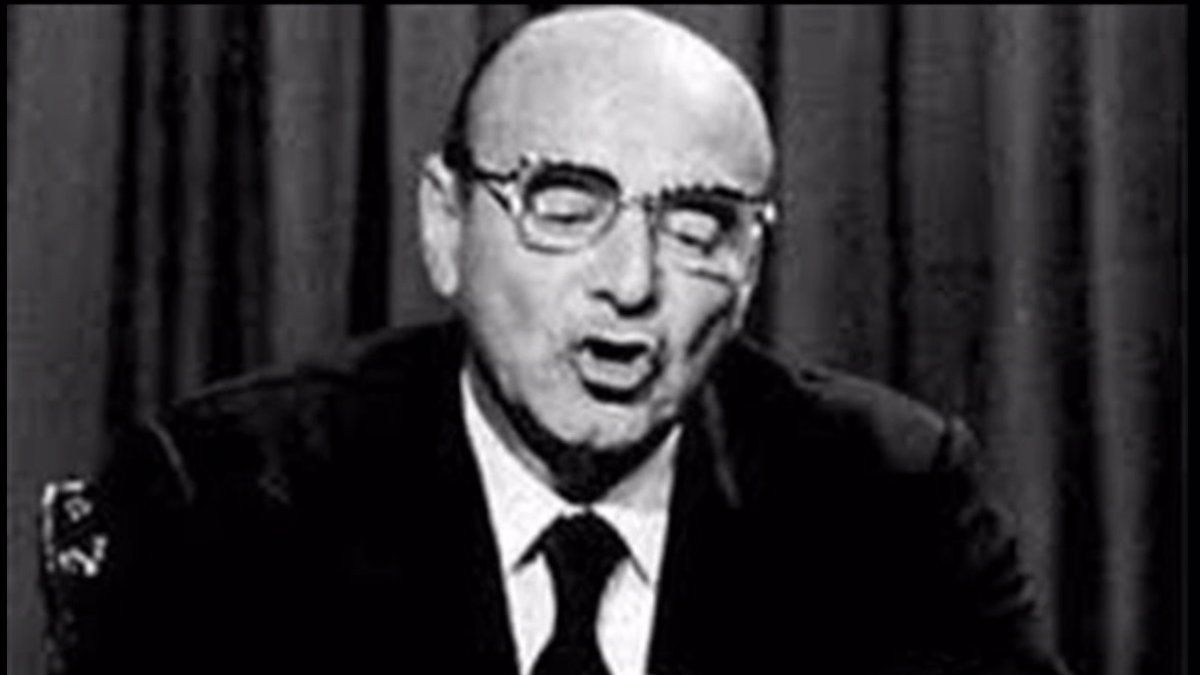

“The Rodrigazo is the image of adjustment, of the attack on the pocket, of inflation, of the loss of savings.” The measures that he announced were a devaluation of the “peso ley” of 61% in relation to the commercial dollar and 100% for the financial one; the doubling of the exchange rate for the tourist dollar, which went from 10 to 45 pesos, the average increase of 100% in all public services and transportation, the increase of up to 180% in fuels, and 75% in electricity rates and an 80 percent rise in wages (Marcelo Rougier).

The true decadence begins

The economic context in which this brutal adjustment took place could not be better. Since 1964 the country had 11 years of consecutive growth that the “Rodrigazo” would turn into a recession, unemployment of 2.3%, a dynamic industry with competitive sectors and the gap between the income of the richest 10% and the poorest 10% It was 12 times – in 2020 it was more than double. (Marcelo Rougier, Martín Fiszben) “The frustration of an economic project: the Peronist government of 1973-1976”).

So that the origin of the end of 2001 can be conceived, we said that the import trend of the main and fundamental component for the ISI model of import substitution (auto parts, machinery and the like), begins in the 70s with 33% and ends with 17.5% in 1975, so it is possible to distinguish a clear decreasing trend (See Brenta, 2013).

In relation to exports, the main buyer of Argentine products during this period is Italy (with 12% of exports), while East Germany (8%) and West Germany (7.5%) are in the second and third place respectively. The United States is the American country that imports the most Argentine products in the period with an average of 7.3%. Regarding the composition of exports, the main product is corn with 14%, followed by beef with 12% and wheat with 7.3% on average at this stage.

According to this panorama, it is evident that the core of exports is made up of primary products that are destined for industrialized countries with which our country maintains an increasingly asymmetrical trade relationship. A clear example of this issue is given by the case of West Germany and East Germany with whom we maintain an unequal relationship regarding the value of export / import products (Brenta).

Now, regarding the trade balance, this phase shows a series of ups and downs, leaving three years with a surplus and two with a negative balance. The period opens with a favorable trade balance of US $ 79,125 and closes with a negative balance of US $ 985,237.

In addition, the commercial balance of this phase, taking as a series its six years that compose it, yields a favorable balance of US $ 329,041. Despite the ups and downs, this period reflects a certain order in public accounts around trade, which, in principle, seems to set the stage for the future paradigm based on a monetarist approach to the balance of payments. It is there where the new rules of the game will be imposed, oriented towards a neoliberal model, where the idea of “deficit” increasingly resounds as a warning alarm (ibid).

On the other hand, regarding the monetary volume, imports are increasing throughout the period, while exports show an increase until their last year, 1975, when they fall sharply. This scheme reveals that the country needs a growing and progressive volume of imports to continue carrying out its ISI (import substitution industrialization) model, while it also shows its other side represented by the need to increase exports to remain in force. Therefore, as exports fall periodically (in relation to imports and also in relation to the volume of exports in relation to previous years), the path that this productive matrix has crossed until now is in jeopardy (ibid).

Regarding the financial issue, the following data should be highlighted. On the one hand, during the period analyzed, the country’s total external debt grew progressively, starting the cycle with a balance of US $ 3,875 (in millions of dollars) and ending with a debt level that amounts to US $ 8,085 (in millions of dollars). In other words, throughout these six years the level of debt increases by a percentage greater than 100%, with 1975 being the year in which the level of debt grows significantly (from US $ 5,514 to US $ 8,085 in millions of dollars (ibid).

Remember it, the Rodrigazo (1975) by Celestino Rodrigo, happens one year after the death of Juan Perón. The minister communicated a series of economic measures that would be a hinge in Argentina’s economic, social and political history.

Behind the Minister who placed all eyes, were Ricardo Zinn-businessman who would continue working with the Military Junta and Pedro Pou-designated Minister of Economy of the Province of Bs.As. of the civic-military dictatorship- “Chicago Boy”. The latter seems less fortuitous.

Clearly, with the constant growth of the debt, Argentine economic policies are beginning to be more permeable to the political-economic guidelines coming from the multilateral credit organizations. In this way, the level of debt will represent an increasingly significant portion of GDP, which will undermine the possibilities of sovereign decision regarding the economic, commercial and industrial development of the country (ibid).

In summary, this period has shown us how our country’s relationship with the world has developed. There, it was possible to observe how its commercial aspects accounted for a reality that was beginning to darken. Asymmetric relations with industrial countries and progressive problems in terms of trade balances show this panorama of incipient (but growing) gloom.

At the same time, it has been seen that the financial aspect has begun to gain more weight in the reality of our land, showing glimpses of its potential capacity to hinder sustainable development paths for most of the population.

Therefore, it seems that with the crisis of the Welfare State together with the structural problems (in economic matters) that Argentina presents (periodic imbalances in the balance of payments), the doors are closed to an advance in its productive diversification. This means that the country’s relationship with the rest of the world is increasingly unequal as a result of the dissimilar prices of exported raw materials with respect to technical products made by industrial countries.

With the consolidation of the “reprimarising” path of the economy together with the imminent advent of a model of capital accumulation with a financial base, the subordination relationship intensifies. Long-term planning, productive investment and industrial development are beginning to move away from the Argentine reality. As a counterpart, the growing burden of debt service emerges in the national accounts, the increase in financial speculation and the loss of sovereignty in decisions concerning sensitive matters in Argentina.

The return of Cavallo

All these tensions were notoriously deposited on the institution of the Minister of Economy. This portfolio led domestic economic policy and also foreign economic policy, despite the fact that, according to the letter and spirit of the historic Constitution, the latter should fall into the hands of Congress. The minister was also, by action or omission, the manager of external shocks and economic-financial globalization.

Cavallo’s return was, therefore, the desperate restoration of the role of the Minister of Economy in a context of global crisis. Argentina faced the risk of a default. As indicated by the galloping country risk rate, that possibility left no doubt. Cavallo, endowed with full faculties, and guided by his ambition, was about to make his biggest miscalculations.

The difficulties studied up to here focused on the asymmetry and the inability to reconcile the technocratic project that de la Rúa adopted (long before the “spiralization” of the crisis, as we explained in previous articles) with the Frepaso political project and a part not less than the UCR. The spirit of collaboration at the national level did not spread too much and “zero-sum competition between the two forces” continued; although the success of the Alliance in the elections, “especially in the big cities”, forged a consolidation in the “’Alliance identification’ of the electorate” (Novaro); This did not translate into a convergence of strategies and options, but only in the continuity of the agreement and the increase in the costs of an exit.

In this context of uncertainty, after the crisis of the coalition, a hasty technocratization project appeared, starting with the arrival of Cavallo. It will continue tomorrow.

Professor of Postgraduate UBA and Master’s degrees in private universities. Master in International Economic Policy, Doctor in Political Science, author of 6 books. @PabloTigani

Source From: Ambito