The literature has found sufficient evidence to justify the presence or intervention of the Government (at its different levels) under two main principles: correct resource allocation failures and redistribute income to maximize social well-being.

For this, the implementation of a public policy measure must respond to the criteria of progressiveness with a pro-humble focus. What does this imply?: that the benefits provided by a public program, measured in terms of income, decrease the greater the well-being of the individuals. And, furthermore, the financing allocated to public policy (subsidies) is strongly concentrated in the lowest segments of the income distribution. That is, public funds are focused to a greater extent on contributing to the most vulnerable sectors of society.

However, the poor design of a public policy or the poor financing scheme chosen for it can generate opposite effects: a A policy that is designed with a progressive character can become regressive or have a pro-rich concentration..

The case of energy subsidies seems to be along those lines. The relative importance that it took on a budget financed with an inflation tax and the little segmentation that has been given to the instrument generated strong distortions in the relative price structure and mainly in the distribution of benefits.

This is in line with the evidence that several authors have capitulated under the name of subsidy targeting problems. The errors in the subsidy policy led to, for example, in the AMBA, the two poorest deciles appropriating 15% of the total subsidies while the two richest deciles of the distribution appropriated 25%.

Distributive incidence of electricity subsidies in the AMBA | Appropriation and relative incidence according to per capita income deciles

Clipboard01.jpg

Fountain: Bertín, O., T. García, F. Pizzi, A. Porto, J. Puig and J. Puig (2024). Revisiting Distributional Effects of Energy Subsidies in Argentina. CEDLAS Working Documents No. 331, June, 2024, CEDLAS-National University of La Plata.

There have been few efforts to achieve adequate segmentation of rates, and like a pendulum, the different administrations have only put on the table a single decision that leads to two possible paths.: delay rates (as a kind of anchor to avoid inflationary problems) either sincere them (rate equal to the actual cost of providing the service or as close as possible).

The first contributes to easing families’ fixed expenses, which leaves greater disposable income to boost consumption – even if it generates fiscal deterioration. The second, as if it were a mirror, reduces income, affecting consumption possibilities – which has a strong impact on economic activity – but frees up fiscal resources.

Thus, in the years of greatest economic activity, subsidies gained participation in the dynamics of spending, while they contracted in recessionary years. Thus, subsidies have become more of an instrument of fiscal policy than a redistributive tool (as it should be).

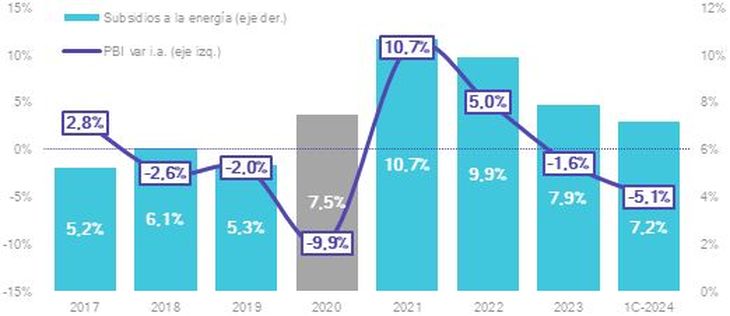

Procyclicality of energy subsidies | Energy subsidies as a % of total SPN expenditure and variation of GDP

Clipboard01.jpg

Source: Own elaboration based on National Budget Office (ONP) and INDEC.

The accessibility of the energy system, the price that users are able and willing to pay, is partly determined by the weight of tariffs on household income. The lack of instruments to segment the cost of energy according to income capacity generates strong distortions in consumption. Through tariff delay, energy consumption is exacerbated in the expansionary stage of the cycle – mainly in the highest income deciles – but the distortion of tariff prices and the immediate correction in recessionary cycles deepens the regressive effects. Rate corrections in this latter context accentuate the asymmetries between households.

The strong regional disparities in income between the North, South or Greater Buenos Aires (GBA) region bring about different costs of living as well as different consumption structures. The income structures of families in the North tend to be more sensitive to recessionary processes and fiscal adjustment, due to the higher levels of informality in the labor market and the impact of income transfers (AUH, Alimentar, PNC, among others) on family income.

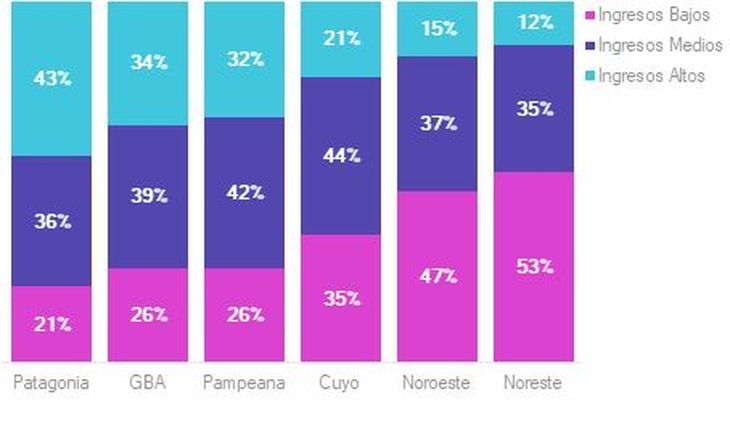

Distribution of household income by region | % of households by income segment over the total

Clipboard01.jpg

Source: Own elaboration based on ENGHO 2017-18 – INDEC.

It is clear that any policy of “tariff delay” implies concentrating the benefits in relatively richer regions such as the AMBA or the South – which also has its Cold Zone Law –.

While in the Northern regions the adjustments and imbalances “hurt more” because their income structures are weaker. In times of loss of purchasing power, informal income components in these regions suffer an even more severe deterioration than official statistics reflect. If we add to this the fiscal adjustment process, where social benefits and retirements are liquefied, the outlook for consumption becomes even more complex. Tariff increases without a solid redistributive criterion are extremely harmful to regional economies.

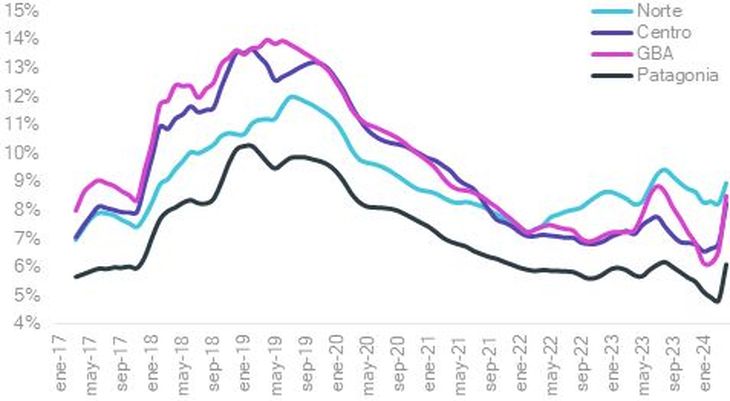

Incidence of household energy expenditure | Energy spending as a % of Total Family Income of an average household; in 3 month moving average

Clipboard02.jpg

Fountain: Own elaboration based on ENGHO, IPC, CVS, AUH and retirement benefits

Provincial administrations also have an important participation in the final cost to the user by updating the provincial VAD. For example, several provincial efforts during the pandemic have cushioned the rate adjustment by assuming provincial costs instead of transferring them to the user.

In the Chaco of Leandro Zdero, these efforts to mitigate the effects of the crisis are null. In a process of “tariff honesty” it updated the provincial component +200% for low-income households: an N2 household with average consumption of 450 Kwh will go from paying $10,500 to $32,000 when the salary of a police officer, for example, is around $400,000 ; These increases are still pending, those announced by the National Government in recent weeks. In 5 months we will reach a 400% increase for the most humble.

A first segmentation considering payment capabilities is necessary to discuss the tariff policy. But our country also constitutes an extensive territory with strong heterogeneities (infrastructure, expenses, income, demographics, resources, etc.), which requires a federal view of the structural conditions throughout the territory. The lack of coordination between levels of government ends up deepening the adjustment processes. All of this means that we are far from recovering the subsidy policy as a redistributive instrument and we will continue in a pendulum fashion, burdening the most vulnerable sectors with the cost of an irrational adjustment.

Economist

Source: Ambito

David William is a talented author who has made a name for himself in the world of writing. He is a professional author who writes on a wide range of topics, from general interest to opinion news. David is currently working as a writer at 24 hours worlds where he brings his unique perspective and in-depth research to his articles, making them both informative and engaging.