He lived through the wars in Vietnam and Iraq, between Arabs and Israelis, and survived a massacre in the Lebanese civil war. The images he brought back from there and elsewhere shaped him star over decades. Jay Ullal has now died in Hamburg at the age of 90.

On the occasion of the death of Jay Ullal, the star published this text from 2018 again.

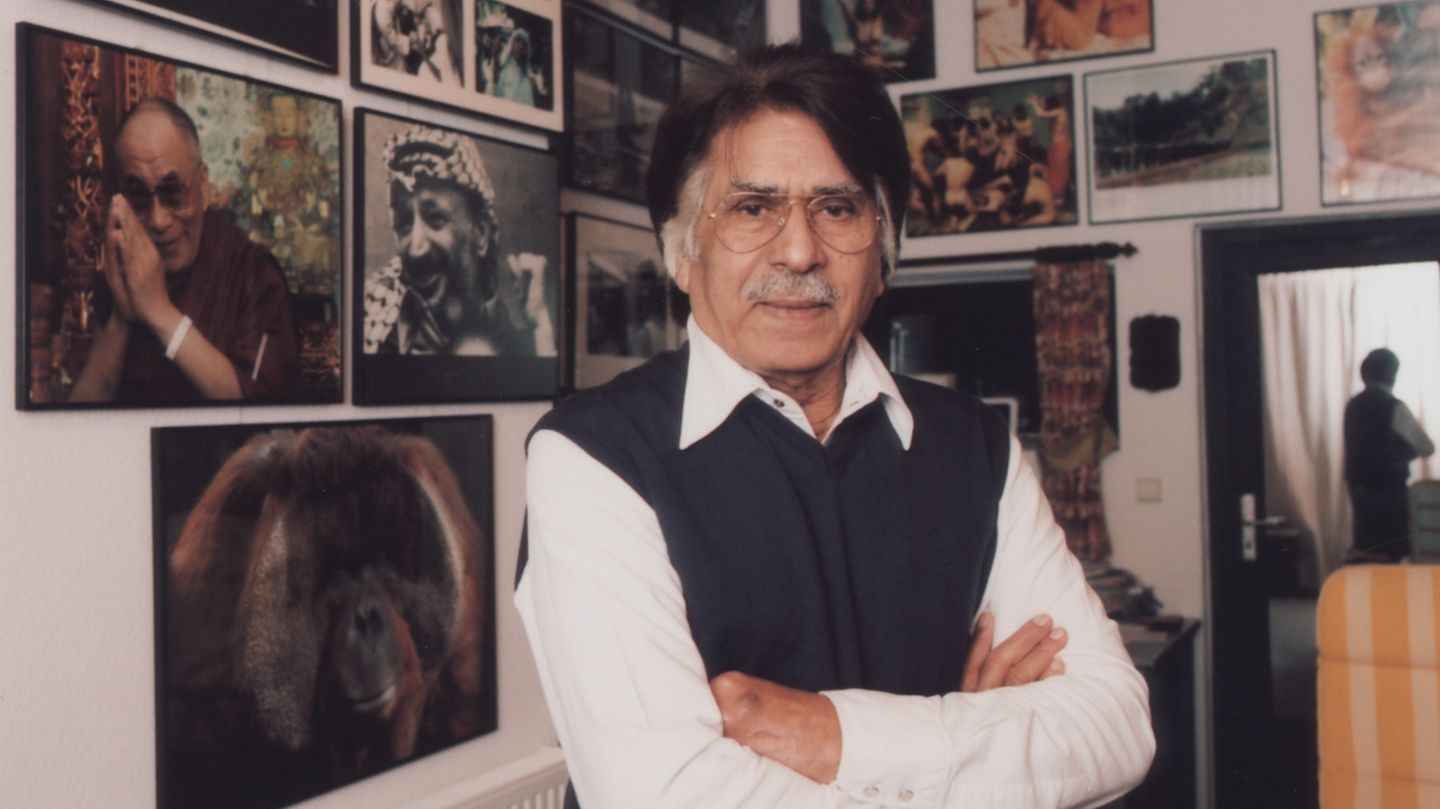

“Anytime!” Jay Ullal called into the phone. “Come over.” On a Friday afternoon he opens his front door in Hamburg-Poppenbüttel, shortly before his 85th birthday, he looks younger. His new iPhone is on the table, he has just discovered Whatsapp for himself.

His house: narrow at the front, a German pitched roof. It opens to the rear, the Ullals have added and created a little India. The chairs made of wooden ornaments, embroidered orange cushions. The carpet on the wall is a gift from the Dalai Lama.

Jay speaks German fairly well, mixing it with the English he learned as a child. Linguistically, he stayed between the two worlds.

Rajni, his wife, offers coffee, but Jay wants to make it himself. He disappears into his area next door. He has a small kitchen there. And only here they hang on the wall: his photos. Here he works in the midst of his work: Willy Brandt shaving in the morning. A wedding couple in Beirut in the middle of the civil war. Arafat without a cloth, with a bald head.

When the Christians were massacred

Jay Ullal prepared as if he were still employed by the star and he would have gotten an order. He has the folder with his star-Stories laid on the table. It must be over 300. Next to it are prints of some of his war pictures. “You want to talk about the wars,” he says.

He starts right away, straight into the story that is his life. That’s how he threw himself into the world back then.

It was only three hours from Damascus to Beirut, but the border was closed. Jay found a truck driver who delivered the newspapers to Beirut every morning. The man allowed himself to be bribed. Only: Herrmann thought it was too dangerous. They had a drink. A few hours later, when Herrmann was at Jay’s door, he said, Come on. We’re driving.

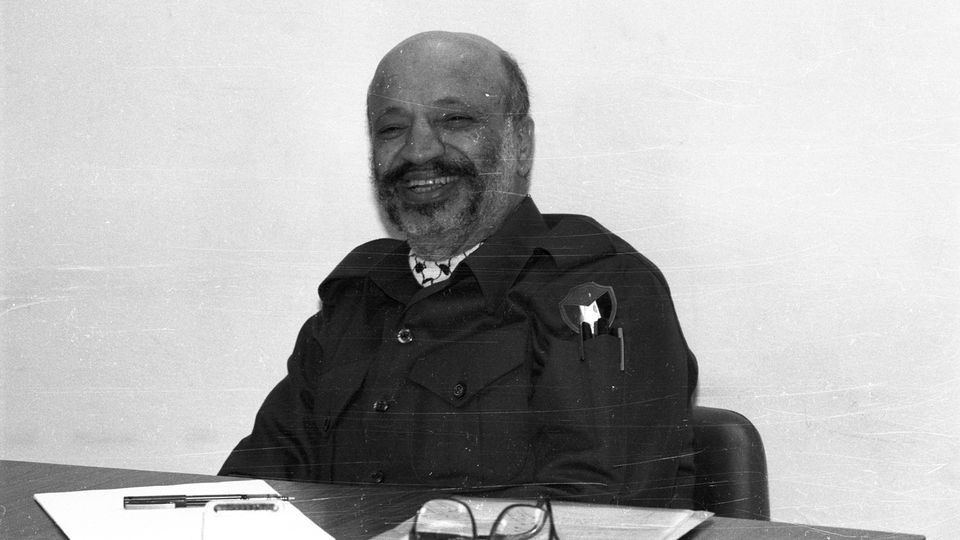

At seven in the morning they met Yasser Arafat in Beirut. The PLO leader resided in Lebanon at the time. Jay had his contact. They should go to one of the Christian villages, said Arafat. To Damur, a town south of Beirut on the coast. With the letter from Arafat in hand, the star-Let people through.

They got revenge. Muslim fighters overran Damur and massacred any Christians who had not already fled. They shot her in front of Jay’s camera. He caught the eyes of the doomed. Then their bodies. And the killers. What was he thinking? “It’s a good thing I put in a new film.” Kai Herrmann ran out of the village and sat on a hill. Meanwhile, Jay kept taking pictures until one of the killers freaked out and knocked him unconscious. When they returned to the editorial office in Hamburg, their colleagues congratulated them on the world scoop. Herrmann got champagne, Jay whiskey.

The hunt for the “untold stories”

Listening to Jay is like walking through the 20th century as a movie. It’s also a journey back in time star became famous. Famous for the fact that Henri Nannen and his editorial team wanted to make the world’s most exciting magazine every week. That was the ambition. And it meant a never-ending search for the “untold stories,” as Jay says, the exclusive, the untold stories, the kind that everyone wanted to read right away. And see. Through the camera of photographers like Jay.

Jay Ullal had been on the editorial board since 1970, and it wasn’t until the end of the century that he quit. A follower of Henri Nannen once said that Jay had it star first made into the magazine for photography.

This magazine always wanted to be a little less provincial than the country, and Jay was the opposite of provincial. Jay has the star experienced. And the star experienced Jay. His view of the world, which was different, if only because he didn’t grow up in the economic miracle, but in a developing country. Because he knew how to get by. How to survive in the jungle and war by speaking the people’s language.

Jay had two weapons: his politeness, and his street cred.

A prophecy comes true

When he talks today, this afternoon in Poppenbüttel, it’s as if his whole life had been one big story. One of the photos on the wall shows Jay as a baby next to his brothers and aunt in a sari. A fortune teller prophesied that he would travel around the world with small devices. His father, a civil servant, believed the man, the boy would become a surgeon, he thought.

Jay bought a camera for 15 marks. He broke out, went to Mumbai, started as a cable porter in Bollywood and got into the film business. All he really wanted was: away, far away, and out into the world. To experience something.

For the “Times of India” he drove to the Chinese border, where the Dalai Lama was expected. The Dalai Lama went into exile. Journalists from all over the world were waiting for him in the middle of the province. But only Jay got a tent from the Indian army and a ration of rum every day. “Army rum,” says Jay, as if he still had the taste on his tongue: “Very good rum.”

Rolf Gilhausen was there for the star. The noticed Jay’s rum stash. And Jay said, “No problem, sir.” He spoke to the major, who was happy to make the German guest happy. It was Jay’s first contact with him star. And his future boss.

His stash of rum brings Jay to the stern

He married Rajni against the wishes of the family. On a trip to Europe, the two broke up, and thanks to Gilhausen, Jay got a job at the magazine “Constanze”. home stories The rich and famous of the ’60s. The Marriage of Jackie Kennedy and Aristotle Onasssis. Henri Nannen was annoyed when he saw Jay’s photos in Constanze.

When Constanze was hired, he changed. Gilhausen made Jay an offer. Jay, however, wanted to take a German course first. While Jay was learning German in Lüneburg, Nannen asked the Hamburg editorial office: “Where’s my Indian?”

He invited him. Jay signed the contract on the same day. And Nannen had his secretary refund the money for the language course in cash. “You don’t have to be able to speak German to work here,” said Nannen. “I want you to take pictures for me.”

Above all, Jay heard Henri Nannen say: Drive off. Or: What are you still doing here, get on the plane.

Always wars

This star wanted the world. Nannen paid his photographers better than the reporters who wrote. They also got more space in the magazine. And to this day, the texts should tell the best story like photos: up close and observing instead of commenting.

Jay was right here, knowing that surprising stories can only be found outside, often by accident, never at the conference table in Hamburg. Jay was on his way. Constant. Above all, again and again, in wars.

He experienced the US wars in Vietnam and Iraq, the Arab wars against Israel. And he went to embattled Lebanon more than sixty times.

In Beirut he was sitting in a hotel room with a reporter one evening, they were playing cards, and suddenly they were shelled. We have to get out, said Jay. No, said the reporter, I’ve got such good cards right now. We have to go, Jay said, right away. Not because he was afraid. He wanted to photograph what was happening outside.

They were standing by the pool when a shell hit the hotel. Later they wanted to go back to their room. It was completely destroyed. “Sometimes it’s luck,” says Jay. “You know.”

Another reporter had a heart attack while they were already in the car from Beirut back to Damascus. They took him to the American hospital in Beirut, the man survived, but he never went to war zones again.

yeah yeah

At home everywhere

In the 80s he was kidnapped in the Philippine jungle. Jay and the reporter accompanying him were told to kneel, the leader aimed his pistol at the reporter. He had no more words. But Jay: “Think about it, Commander,” he said. Calm down. “We can do business. Nobody pays you anything for a dead white man.”

In doing so, he saved his and his life. The star paid $20,000 for his employees’ freedom.

A starThe reporter, with whom Jay traveled a lot in the Balkans, was called Gabriel Grüner. He once asked Jay: How do you deal with all the horror? “I don’t stop taking pictures,” Jay said.

Did he ever get to the point where he couldn’t take it anymore? Sometimes, says Jay. He drank a lot of whiskey in the evenings, the next day he went out again early and worked.

Once he went to Nannen. He doesn’t just want to make wars anymore. Suggest something, Nannen replied. Jay then traveled along when German Neckermann tourists descended on Indian Maharaja palaces for the first time. He found other Germans in Puna, in the commune of the guru Baghwan, where they forgot each other while having group sex.

Love. That’s it when Jay by Henri Nannen and vom star told. The star was never just a job for either of them. You could tell from the notebooks. It was weekly devotion.

Jay became such a person who is at home anywhere. Who knows someone everywhere. Perhaps that word suits him well: a “citizen of the world.”

A lifelong trip around the world behind him

The conference was about a report on the death cult on Sulawesi in Indonesia. Jay held up his hand and said, I know the President’s son-in-law. He called him right away and got the permit. It became a “big color” as it was when star means: seven double pages of photos. “Fantastic,” says Jay. He can still be happy about it, forty years later.

He sits in his room in Poppenbüttel and easily changes continents, airports, stories. Sarajevo. Palestine. The Rwandan Genocide. The “coup in paradise” in the Comoros. Vietnam. Beirut, again and again.

When he photographed the massacre in Damur, he flashed into a room where an old couple was lying on the floor. Above them one of the fighters, he was about to shoot them. Jay’s flash bothered him, he went for him. Later, Jay got a letter from their son. Jay’s flash had saved their lives.

Jay is now 85 and still has the eyes of the baby in the picture on the wall. At that time he knew nothing but his town in southern India. Today he has a lifelong trip around the world behind him. He got to know people at their best and at their worst.

He says that if he got an exciting job today, he would drive off again straight away.

This text first appeared on stern.de on October 1, 2018

Source: Stern

I have been working in the news industry for over 6 years, first as a reporter and now as an editor. I have covered politics extensively, and my work has appeared in major newspapers and online news outlets around the world. In addition to my writing, I also contribute regularly to 24 Hours World.