I have been working in the news industry for over 6 years, first as a reporter and now as an editor. I have covered politics extensively, and my work has appeared in major newspapers and online news outlets around the world. In addition to my writing, I also contribute regularly to 24 Hours World.

Menu

China’s “new Silk Road” turns 10 – the celebratory mood is deceptive

Categories

Most Read

Dispute over military service: Union insists on changes to Pistorius draft

October 15, 2025

No Comments

Retirement provision: Cabinet decides on active pensions – overall package

October 15, 2025

No Comments

Israel: Body handed over by Hamas was not hostage

October 15, 2025

No Comments

Conflict in the Middle East: Army: One of the bodies handed over was not a hostage

October 15, 2025

No Comments

Hamas releases video of public execution

October 15, 2025

No Comments

Latest Posts

The best memes from Argentina’s victory over Puerto Rico: pearls, debuts and Daddy Yankee

October 15, 2025

No Comments

October 15, 2025 – 10:40 The National Team beat Puerto Rico in a friendly and Lionel Scaloni’s team is already thinking about the six games

Bitcoin rebounds after the largest liquidation in history: the crypto market breathes, although it remains cautious

October 15, 2025

No Comments

October 15, 2025 – 10:21 Despite the recent collapse in leverage due to Trump’s tariff threat to China, analysts maintain positive outlooks thanks to Powell’s

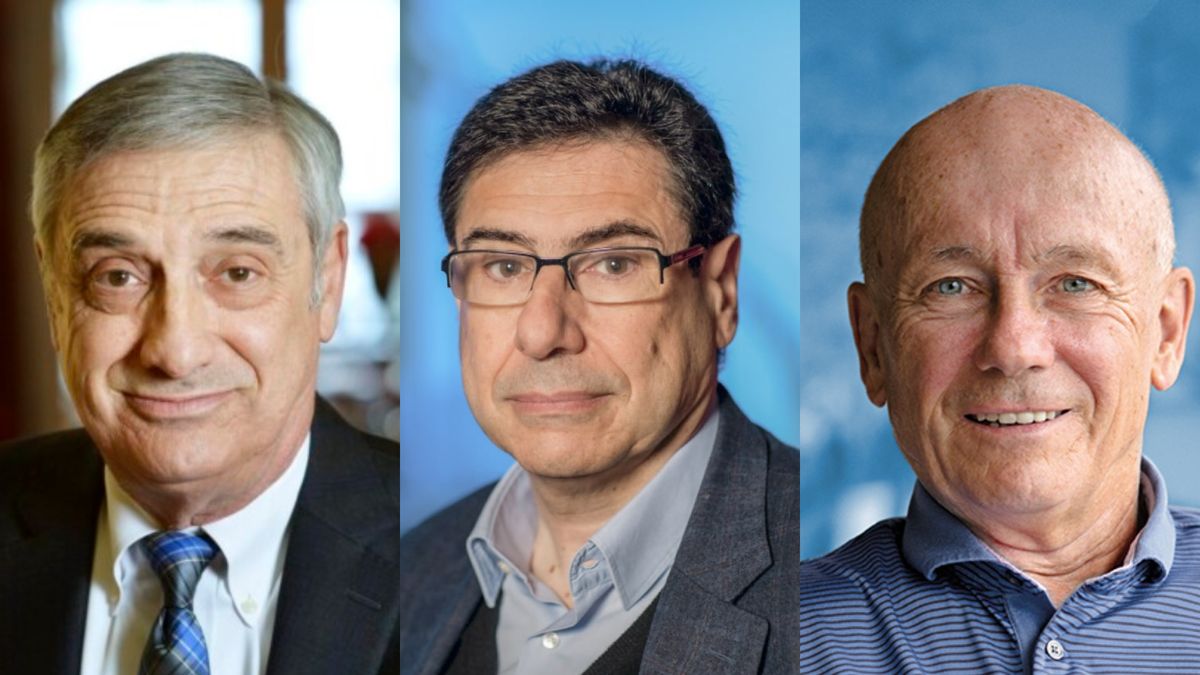

Nobel Prize in Economics 2025: Recognition of innovation in economic growth

October 15, 2025

No Comments

This year’s Nobel Prize in economics recognized Joel Mokyr from Northwestern and Tel Aviv Universities, Philippe Aghion from the College de France, INSEAD and the

24 Hours Worlds is a comprehensive source of instant world current affairs, offering up-to-the-minute coverage of breaking news and events from around the globe. With a team of experienced journalists and experts on hand 24/7.