disinformation

Deepfakes: How dangerous are AI forgeries for the election campaign?

Copy the current link

Deepfakes and fake videos have long been part of the election campaign. How do they influence our trust in politics? And how can we protect ourselves?

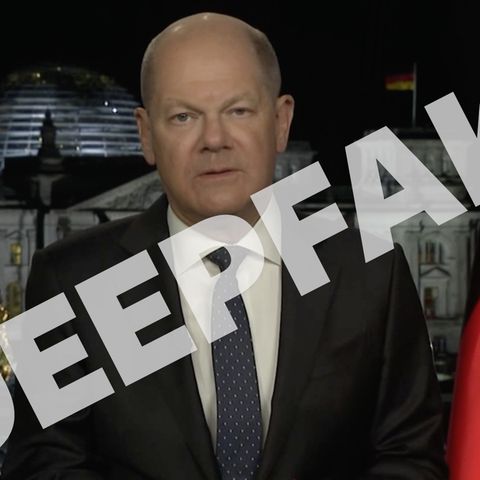

Olaf Scholz does a somersault over the lectern in the Bundestag and punches in the air. At least that’s what it seems like on a viral video on social media. But the clip is a fake – a deepfake.

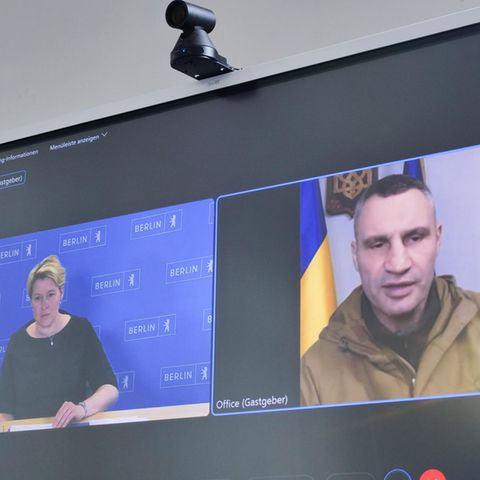

Such fake videos have long since become popular in the election campaign. SPD member of the Bundestag Bengt Bergt posted a clip on Instagram last November in which CDU leader Friedrich Merz said: “Ladies and gentlemen, we despise you! And we despise democracy.” The big problem: Of course, Friedrich Merz never said anything like that. The CDU candidate for chancellor addresses the deepfake in a speech in the Bundestag, SPD parliamentary group leader Rolf Mützenich forces his own MP to apologize to Merz. This matter seems settled – but the bigger question arises: How dangerous are these so-called deepfakes really for our democracy?

Deepfakes use artificial intelligence to create videos that appear deceptively real. “Today, anyone can anonymously create AI-generated images and videos and use them, combined with text, to spread disinformation,” says Dominique Geisler, who researches deepfakes at the LMU Munich. Thanks to AI, a human can do or say anything – at least apparently. Anyone can create such videos using simple apps.

Particularly problematic: The technology is getting better and better. “We will probably reach a point where we can no longer distinguish whether something is real or AI-generated,” predicts Geisler. “The first time you might think: ‘This is nonsense’, but after ten or twenty encounters you might start to believe it,” warns the LMU researcher.

Deepfakes: “It certainly won’t influence the outcome of the election”

The good news: There is partly an all-clear for this election campaign. The reason sounds banal: people are often smarter than you think. “Extremely misleading statements are not particularly harmful,” explains cyber expert Ferdinand Gehringer from the CDU-affiliated Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS). “Let’s say a deepfake exists of a politician saying, ‘I hate democracy.’ Only people who already don’t like that person would believe that.” At the same time, Gehringer emphasizes: “Disinformation does have an impact, we know that. We don’t know how big this impact is. But it certainly won’t influence the outcome of the election.”

However, part of the problem is much more trivial – and therefore more dangerous: “We talk a lot about deepfakes because their quality can be impressive and it is fascinating what the AI creates,” says media scientist Viorela Dan from the University of Innsbruck star. She warns: “But people don’t need such convincing ‘evidence’ to be deceived.” A quote taken out of context, a cleverly edited video, a changed context – these simple “cheapfakes” can be far more effective than elaborately produced AI fakes.

“It’s good that we’re talking about the dangers of fake videos,” says Dan. “But the use of AI is not the point here – but rather the use of supposed visual evidence for explosive claims.”

The real challenge lies in the spread of misinformation, not in how it is created: “Two big problems are coming together,” warns Gehringer. “The spread of disinformation – including deepfakes – on social media. And that there are many actors internationally who have built up the best conditions to use these means.” Russia in particular has perfected its disinformation machinery.

However, Germany is not unprepared. “Especially in Germany, our politicians have a certain sensitivity when it comes to deepfakes,” says Gehringer. The Merz case has shown that if a limit is crossed, there are – at least for now – quick consequences.

So what to do? “It takes a combination of different approaches,” says Geisler. “Technical solutions such as watermarks for AI-generated content are one possibility. But above all, we need to strengthen people’s digital media literacy.”

The irony is that while everyone is trembling at the increasingly perfect AI deepfakes, the simplest manipulations often have the greatest impact. Perhaps that is the most important takeaway from this debate. The old IT saying remains true: “Most of the time the problem is between the keyboard and the chair.” It’s not the technology that’s the problem – it’s the people behind it. No matter whether with or without AI.

Source: Stern

I have been working in the news industry for over 6 years, first as a reporter and now as an editor. I have covered politics extensively, and my work has appeared in major newspapers and online news outlets around the world. In addition to my writing, I also contribute regularly to 24 Hours World.