image.png

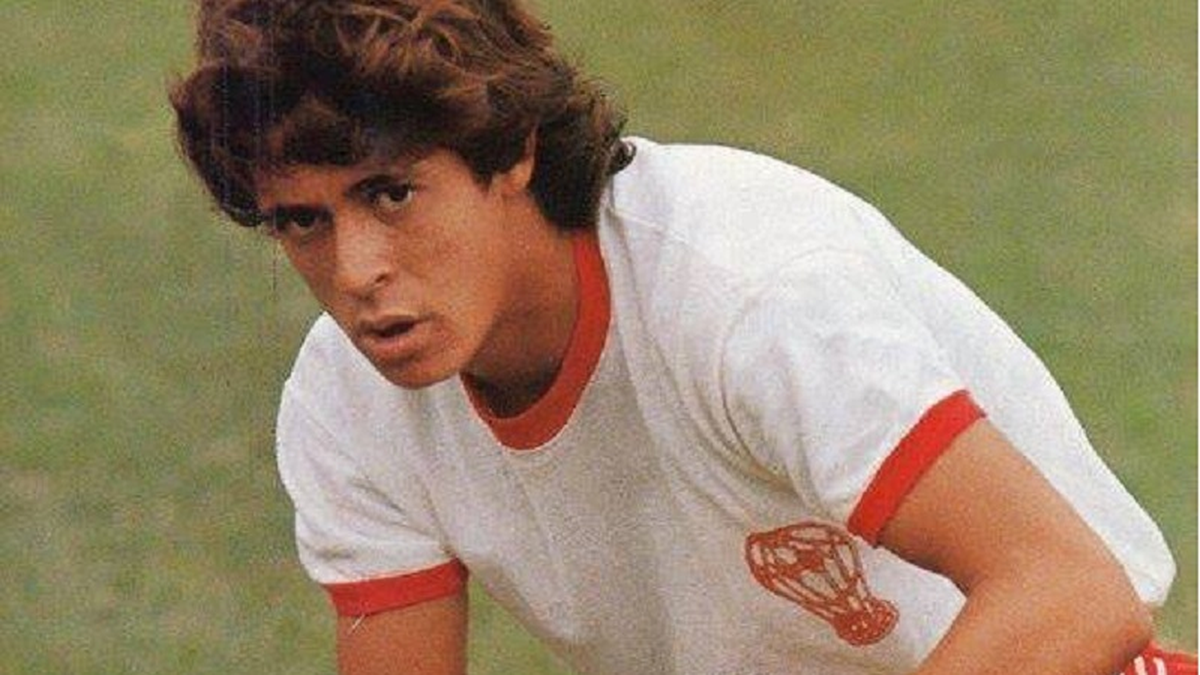

The rumor has been around for a long time: “The ‘Crazy’ Houseman is a shipwreck.” They drew him an alcoholic, abandoned on the streets of Buenos Aires, collecting four coins at the traffic lights to the north of the city, who already knows if he is dead and buried. And yet, from the porch of a bourgeois building, perhaps the greatest winger in Argentine football emerges to explain his own version of history.

Houseman, 60, talks fast, as if he has no time to lose: “I have a problem with my legs and I can’t move much. We are going to eat something. Shall I call a taxi? She has thin calves and a bloated belly. The destination is the clubhouse of your neighborhood club, Hikers, in Belgrano. “Here you find the best roasts in the area,” he justifies himself before disappearing. Suddenly it reappears to confirm that everything is closed. Another taxi. “At the end of the street on the left. Have you seen that blonde? I have passed it through the stone and I assure you that it moves well. Stop, we have already arrived ”. Leaning over the bar of a neighborhood canteen, René Houseman stops moving, but not talking.

The verb brake has never been part of his vocabulary. The legend of Houseman is the one of the type that runs fast over all the lines, those of the field and, mainly, those of the life. His story is that of a wing, the most genuine of all time.

“It’s a kind of mix between Maradona and Garrincha”, César Luis Menotti defined it in his day, when they revolutionized Argentine soccer with Huracán in 1973. And despite everything, when you ask René to pull back memories, he only evokes the sad ones. “Around here they say that the gatekeepers are chickens and the extremes are crazy. It’s probably true. Sometimes he was stuck to the lime for so long that he couldn’t see the ball. I went crazy with loneliness. What are you drinking? Whiskey, beer, wine? For me the alcohol has finished ”, sentence. Piece of meat and soft drink through, the ‘Loco’ does not haggle when asked to define himself. “I am a villager. That is what I have been all my life and that is what I will always be until I die ”, he declares with pride.

In the 1950s, like so many other peasants who arrived in Buenos Aires attracted by the mirage of becoming prosperous workers, Houseman Sr. settled in Bajo Belgrano. But immediately he dedicated himself to a very different chain work: alcohol.

“I hardly even met him. I was very young and he was already very ill. His drinking problems led him to dementia ”, he details. Without his father, René’s fable takes the same path as that of so many in South America: bare feet, spherical fortune and social misery. The mother sweated the brood forward, but Houseman was a racking bum, and proud of it, who married life to divorce from work. “In the village I did what I wanted, it was the best place in the world for me. It was absolute freedom. I was playing soccer all day to go back to sleep at night, without even washing myself. In fact, everyone knew me as the ‘Pig’. It was dirty, very dirty, but I didn’t care ”, he confesses.

“And suck, suck, suck, don’t stop sucking. The ‘Loco’ is the greatest in national football “, the fans chanted him in all the stadiums.

Spontaneous, free, crazy. Houseman played like he was. Low sock to use the shin as bait for the defender and glued to the side, where the lack of space heightens the spirit of survival. He penetrated the defenses gently, enjoying himself while playing with the defenders. Changes of pace and simple gestures. Short dribble, contact and feint. The code of the street: the man is judged by his actions and not by his words. He does not stick to make himself respected, he sticks when necessary. “He dribbled, he was fast, skilled and he shot with both feet, but I never made fun of anyone. Of course, if someone came looking for me it was a huge son of a bitch. If they looked for me they would find me. And if he could kill someone, he would kill him ”, he sums up.

image.png

A hero of thousands of pasture matches in which the trophy was a handful of pesos, Houseman was soon discovered. In 1973 he ran into a man, Menotti, and one moment, post 68, who will change everything. El ‘Flaco’ has just taken over in Huracán and has a revolutionary idea that will shake the country: high pressure, short game and absolute freedom. To carry it out, he looks at that extreme with an Anglophone surname that comes from scoring 16 goals in second with Defensores de Belgrano in his professional debut. He sees it, he knows it, he signs it.

In February 73, in his debut with ‘Globito’, Houseman received a diagonal from Babington. Control with the chest in the air, crossed left-handed volley and goal. An impossible gesture that uncorks a crazy year in which the burning set, inspired by its extreme, makes everyone dream. In a football still dominated by the memory of the violent years of Estudiantes, Huracán scores 46 goals in his first 16 games. Never seen. The Houseman effect is such that even Roberto Fontanarrosa wrote an ode for him.

The ‘Globe’ is the ideal ecosystem for the ‘Fool’ to express himself. Absolute freedom is the only commandment and René takes advantage of it: “I smoked before games and at halftime. Menotti didn’t tell me anything. Today I smoke Marlboro, but at the time I was smoking Gitane, the most murderous cigarette that can exist. Without a filter, it was like a joint and left you high. And that I was already quite touched as normal. Go figure…”.

The workouts were governed by the same pleasure regime, no effort. “When you had to run, he was injured, but with a ball in between he was miraculously cured and was the fastest,” recalls Osvaldo Ardiles, who arrived a year later at Huracán and became his roommate. The day-to-day of the ‘Loco’ as a professional was not too different from the one he had known in Belgrano. He was still living in the village, drinking and going out like the most. The ‘Globo’ even tried to take him to the south of the city without much success: “They rented me a room so that I could live near the stadium. I endured 15 days, I could not bear it. He went out to the street and had a manager in front and another on each side. They looked like the federal police. I immediately went back to my neighborhood ”.

He never respected a concentration, but the problem came with the 1978 World Cup. Three months of preparation in a totally isolated venue, without alcohol or women, from which he could not escape. That ended up sapping his talent. He started the World Cup as a starter, but ended it on the bench, along with his beloved Menotti, condemned to play the last minutes. It wasn’t his tournament: “What happened to me was simple: I overtrained. If they hadn’t demanded so much of me, I would have been the best. After the competition I apologized to the fans. I had the feeling of having betrayed them ”.

image.png

“He did not take anything seriously. Not football, not his teammates, not himself. And that was not an obstacle so that at the end of each game he always ended up being the best ”, defines him Ardiles. Almost too pretty to be true. And yet it is true. After the 1974 World Cup, in which in a transitional Albiceleste he is blatantly the best, offers from Brazil and Europe follow one another. But Houseman has no intention of leaving Belgrano. “Why would I leave Buenos Aires, the most beautiful city in the world?”, He reflects.

In an age when the Kempes, Passarella or Maradona each left earlier than the last, he is the only one to stay. That fidelity establishes him as the idol of the people. “And suck, suck, suck, don’t stop sucking. The ‘Loco’ is the greatest in national football ”, they sang to him in the stadiums.

The song perfectly defines the life philosophy of Houseman, who will miss all kinds of opportunities to complete a great career for his love of the bottle. A myth reinforced by René himself with an anecdote from November 1977: “I went to my son’s birthday and I got drunk. I arrived for a game against River the next day at 11 in the morning and I was still touched. Cold shower, coffee and starting whistle. 20 minutes from the end I scored a goal. Surely being drunk helped me, but I don’t remember anything ”.

Indeed, Houseman’s memories are blurred because they are not all true. “It is false, if I had been drunk I would have realized it. I wore it and brought it to games. He never played drunk ”, Ardiles censures him. Drunk or sober, his career knew little by his talent. “It was a psychological issue. He was on the same level as Maradona, but he never wanted more. That mentality was part of his personality ”, clarifies Ardiles. There was that innate laziness, but also that continuous inner sadness.

In the village, misfortunes were deceived in a group, together with your people. In the world of football, with those large doses of individual selfishness, the ‘Loco’ never felt at home, of which he always felt nostalgic. “I hardly had any soccer friends. That does not exist. Everyone in the end wanted to screw you in one way or another ”, he confirms. But the only place René was happy was on a pitch and the only way to beat melancholy was to make people happy with his talent.

image.png

The balloon had only ephemeral therapeutic effects. “At 19 years old, I already caught the vice of the bottle. I would drink anything. Not at first but soon I started from morning to night. I drank to feel good, because if I didn’t shake. When I left football, my life was only dedicated to that crap that is alcohol “, recognizes a Houseman who lived dominated by drink until a certain day in 1993.

The ‘Loco’, in his 40s, was walking drunk through the streets of Buenos Aires with his daughter. It was loaded up to the bars. “He was an alcoholic, but had never done a number before that date. That day, I fell with my daughter in my arms and was almost hit by a bus. Mentally, that changed me. I got admitted and spent 22 days in the hospital. After that, not a drop more. I haven’t tried alcohol for 20 years, ”reveals the former winger.

Since then, Houseman’s liver has been doing much better, but not much else. “When my mother died, nobody helped me. Nobody. I held out my hand, but nobody grabbed it ”, laments the ‘Loco’. The plate is empty. Put the cutlery on top and ask for “a little help to help the family.”

He says goodbye to the owner of the bar who hugs him. People greet him on the street. As in the good old days, Houseman walks out the front door. “I have had a good time and I have taken advantage of my life. I get up late and then do what I like best: nothing. Anyway, I have nothing. I’ve never had anything. Money I have always thought that it comes and goes. It didn’t do me any good to spend it. In the end, you know what I would have done if I had had a lot of money. I would have built a great village to live with my people ”.

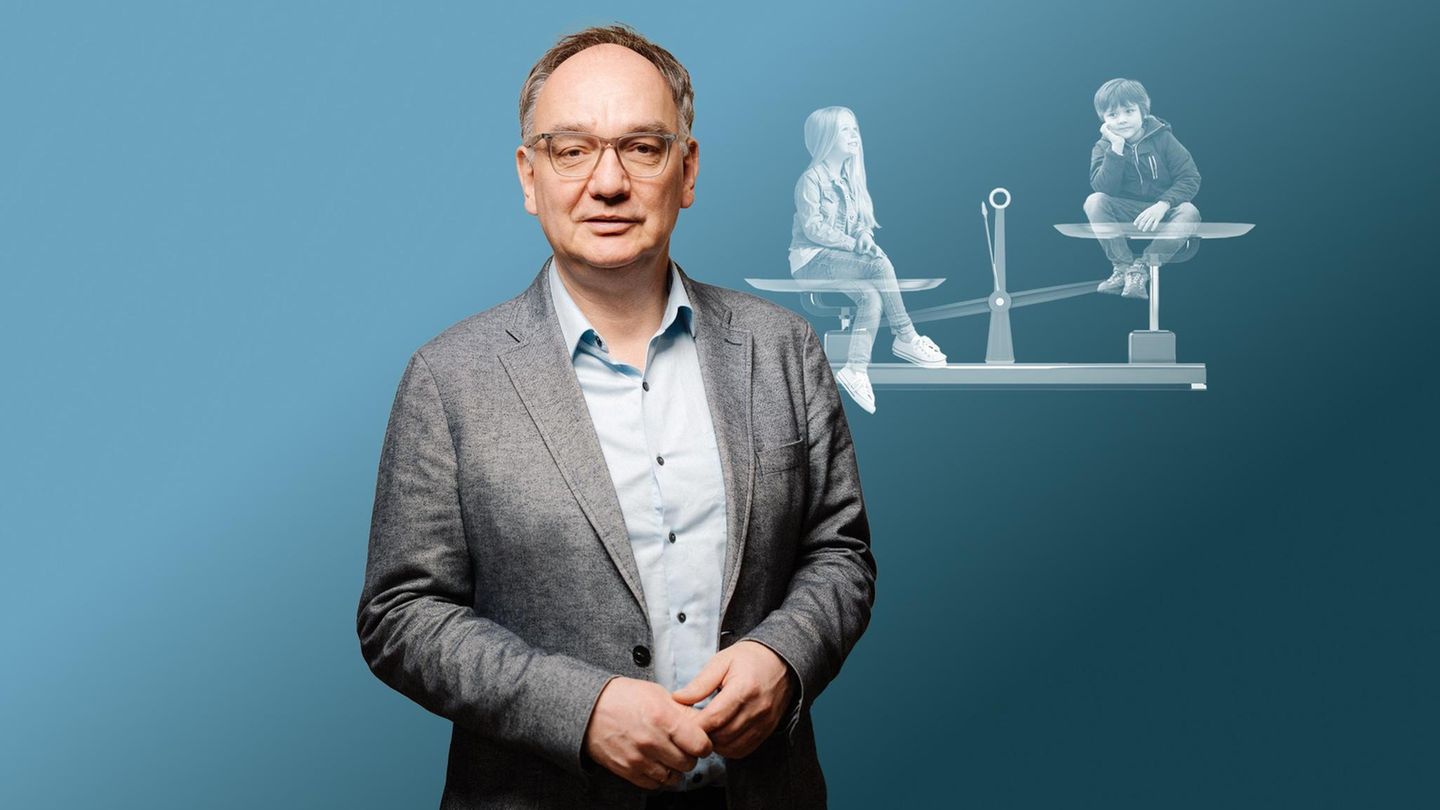

David William is a talented author who has made a name for himself in the world of writing. He is a professional author who writes on a wide range of topics, from general interest to opinion news. David is currently working as a writer at 24 hours worlds where he brings his unique perspective and in-depth research to his articles, making them both informative and engaging.