Last September 13 The Senate approved the University Financing Law with 57 votes in favor, 10 against and 1 abstention. However, almost three weeks later, and after a massive mobilization in defense of university education, the president Javier Milei decided to completely veto the projectwhich he described as “irresponsible” and of “demagogic populism”.

This is how the libertarian administration It constituted his second total veto in just ten months of Governmentafter the rejection of the Retirement Mobility Law of August 30, later reaffirmed by the National Congress.

However, one Most of the vetoes are for technical reasons.and that is why they do not acquire so much media and much less public relevance, even when some of the laws are later ratified by Congress.

The vetoes of each president since the return of democracy

Some presidents have used it more, others less, and others have almost done without the tool. What yes, there is a clear trend: Those who have used it the least are the presidents of the last 20 years. The director of the Political Science degree at the UBA, the political scientist Luis Tonellinoted that this happens because “as bipartisan hegemony fades, It has been more difficult for Congress to pass laws against the President, which is the only one ‘great coordinator’ of legislative wills that have remained.”

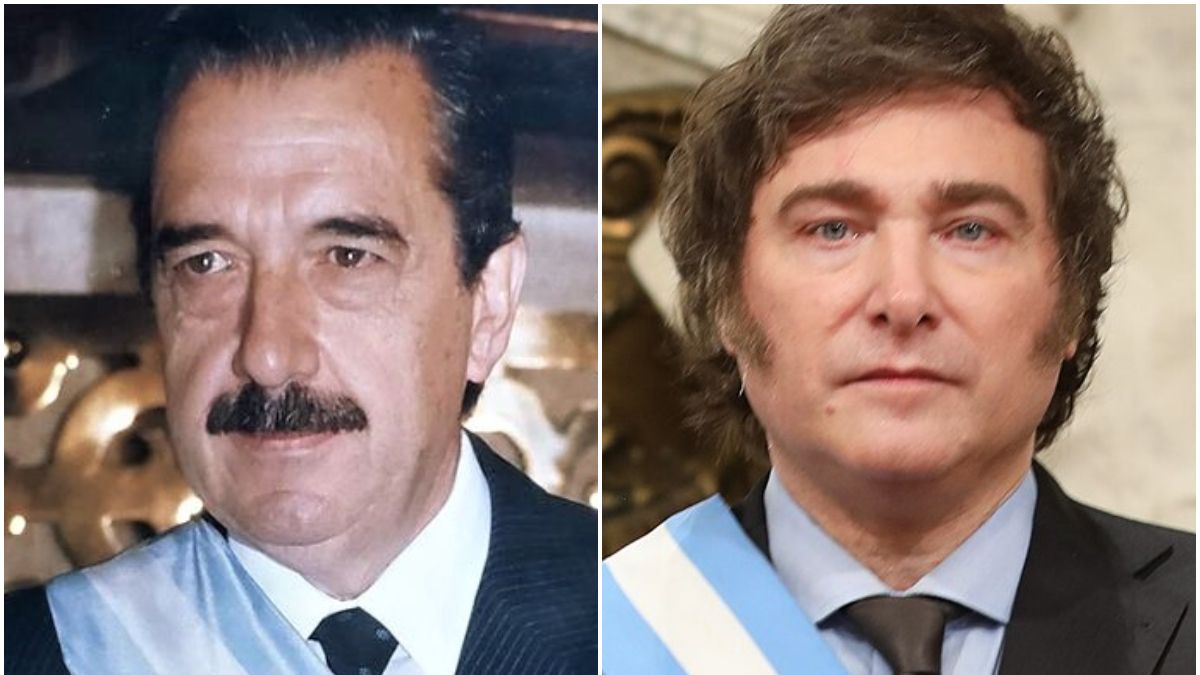

According to a request for access to parliamentary information made by Scope, The president who made the most use of the resource was Carlos Saul Menem. Throughout his two presidencies made 195 vetoes -95 total and 100 partial-.

This has two explanations. The first is logic: the Riojan is the one who has been in power the longest since the return of democracy. However, Tonelli indicated that, since Menem had opposition within Peronism itself, Their legislative majorities were not very large. Given this parliamentary scenario, the veto worked as a tool to “demonstrate the degree of commitment to the course set before international credit organizations and the financial world“said the political scientist

On average, Menem vetoed 12.5% of the laws approved during his administration. This is a higher percentage than its predecessor, Raul Alfonsinwho vetoed 7.5% –there were 49: 37 total, 12 partial. However, whoever has the highest average is Eduardo Duhaldewho in his little more than a year in charge of the Executive rejected 20.4%. Practically He vetoed a law every 15 days.

duhalde.webp

On average, Eduardo Duhalde vetoed a law every 15 days.

For its part, Fernando de la Rúa made 46 vetoesdistributed in 26 total and 20 partial, which translate into 14.1% of the projects approved during his management.

A curious case is that of Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, who was only president for seven days. However, This was enough for him to veto two laws: the National Rail Transport Inspection Rate; and the Regime for Technology-Based Companies – Technological Risk Capital System. Likewise, it is worth clarifying that Both norms were sanctioned during De la Rúa’s mandate.

As for the Kirchners, Néstor had barely more vetoes than his predecessor Duhalde, although in almost three more years. Were 13 total and 26 partial. Cristina, for her part, vetoed 21 laws in her two administrationsalthough only three were total and the other 18 partial. However, one of them took on great media relevance: the rejection of the 82% mobile law for retirees.

Macri only vetoed eight sanctions from Congress -five total and three partial-, while his successor, Alberto Fernández, did it 13 timesbut none was a total veto, all partial.

Why most of the vetoed laws are not insisted upon by Congress

As previously mentioned, once the law is vetoed, Congress has the power to insist that it be passed. However, about 10% of the time this happens.

They insisted on Raúl Alfonsín in one of the 49, Menem in 30 out of 195, De la Rúa in five out of 46, and Duhalde in three out of 37. They did not ratify any of the vetoed laws for the Kirchners, Macri and Fernández . Neither does Milei for now, although It remains to define what will happen with the University Financing Law.

For Tonelli this occurs, in the first instance, because in order to reverse the veto two thirds of each House are neededa difficult number to achieve. But also, because “In politics, the symbolic is sometimes more important than reality.””. That is, most of the time legislators do not act because “Their symbolic gain was already obtained with the initial sanction.”

National Congress Deputies Senate

For Congress to overturn the president’s veto, two-thirds of each House is needed.

Mariano Fuchila

Furthermore, the political scientist noted that the number of insistences against Menem is high because “some of them were promoted by himselfas part of the poker game between internal politics and what had to be shown to creditors and investors.”

Why Milei’s vetoes had such an impact

It is clear that when dealing with sensitive issues such as retirements and universities, Milei’s vetoes impact the public sphere. What happened to Cristina when she vetoed the 82% mobile is similar, although the main difference between both cases is that the libertarian only controls 10% of Congress.

Tonelli described him to the President as “starved” of institutional power. “He knows that it is better to be arrogant than to be impotent,” expands. That is why, beyond the issues in which Milei interferes with his vetoes, It is “his need to show power” that puts him on the agenda.

Source: Ambito

I am Pierce Boyd, a driven and ambitious professional working in the news industry. I have been writing for 24 Hours Worlds for over five years, specializing in sports section coverage. During my tenure at the publication, I have built an impressive portfolio of articles that has earned me a reputation as an experienced journalist and content creator.