Journalist: In your book you state that despite the fact that for you Videla was “the dictator and the murderer”, you always wanted to interview him, why?

Vanessa Cerone: At the age of 15 I discovered Rodolfo Walsh’s “Open Letter to the Military Junta”, and I couldn’t understand what I was reading, how in our country there was a president who allowed disappearances and torture.

Already in college, at 20, a professor asked who we wanted to interview for a final project, and I said: “Jorge Rafael Videla.” She wanted to have him in front of her and ask him about everything he did.

The teacher asked us to get that interviewee to pass the course. That was a push. I went, rang the bell in his college department, and brought him a letter. I knew that it was very likely that he would say no, since he had not given interviews to any journalist up to now.

To my surprise he served me. I told him through the doorman who he was, I introduced myself and told him that I had to do a job for the university, that I had to interview him. He told me that it was not his grace to give statements, so I told him that I left him a correspondence.

Finally I asked him to keep in mind that if his answer was no, I was not going to leave this world without achieving my goals.

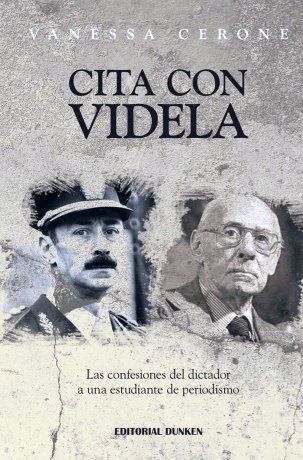

Videla told me that he regretted having been president, that he never wanted to be” (Vanessa Cerone, journalist and writer of “Date with Videla”).

Q: In chapter 2, “Videla calls by phone”, you state that you knew that sooner or later Videla was going to answer you. Why were you sure of that?

I assumed that he was going to call me because, being a student at the Monsignor Jorge Novak Institute, one of the bishops who fought the dictatorship the most, and when I wrote him the letter, my attitude was somehow daring.

I thought there was a good chance that he would answer me, mostly because, as Agustina Kämpfer says in the prologue, I was “an unknown girl who was on a mission”, and that’s how it was.

Q.: Which of all the things that he confessed to you in his meetings surprised you the most, and why?

VC: He made many statements to me that caught my attention and that did not appear in any media.

The first time I interviewed him, I asked him if he had any regrets, and He told me that he regretted having been president, that he never wanted to be.. He told me that “he had to be president and that he had to take responsibility” for what at that time was “a war between brothers”, and that “in a war you fight: it was kill or be killed”.

Asked if he had thought about resigning at some point and he said yesbut also he thought about who would be left in his position if he resigned. I named it to massera and pointed out that he was more moderate. He made me understand that Massera was much tougher and that things could have been worse.

He admitted to me thatthe disappeared are actually dead”.

I asked him about the mothers and grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, and his response caught my attention because it made a difference: he asked me which ones I was referring to, those who really suffered the death of a child, or those who used that to do policy.

He told me that he would help some of them and give them all the answers he has at his disposal to collaborate with their pain, and with the others it would not be possible to speak directly.

Appointment with Videla 3.jpg

Q.: When today, from a distance, you think about the first talk you had, do you remember what you felt? What was going through your head when you heard it??

VC: I felt what any human being feels when facing the person responsible for the disappearance of 30,000 people. But as a journalist, I was inherent in everything. In addition, I feel that I had a great capacity to face strong emotions.

Mainly, I never forgot that 15-year-old girl who was horrified reading Rodolfo Wlash’s “Open Letter to the Military Junta” and wanted to have Videla in front of her. In fact, Kämpfer wrote in the prologue that I could “feel in my chest the pain of an Argentina that still bleeds today”, and that is why I was able to achieve my mission.

The disappeared are actually dead, but that’s what they are called” (Jorge Rafael Videla, member of the Military Junta and de facto president in “Appointment with Videla”).

Q: You went to his house and gave him a letter with the intention of doing a job for a course at 20. Almost 15 years later you publish a book about the experience of your encounters with him. How much did that idea you had from the first interview change to what ended up being the book “Date with Videla”?

VC: I always went with the aim of making this work for the faculty, a book. Once I got the first interview I kept in touch with him and I told him my goal was to write a book.

He replied that this “was not allowed” because at that time he was under house arrest and any statement that leaked to the media could harm him and he could lose that benefit that was what he most wanted: to be at home with his family.

I accepted it, but always thinking that at some point my book would be able to come to light, perhaps after his death.

In addition, at that age I was not ready nor was it time to launch the book, but it was always my goal to tell this story and tell the country the statements I got from “The Dictator”many revealing because Videla hardly even spoke to the media.

Q.: How much did your perception of Videla change before meeting him and after interviewing him in the privacy of his home, with his family and in prison?

My perception of him never changed, he never stopped being the Jorge Rafael Videla that I wanted to interview. I always kept in mind that he was a murderer and dictator. But in the meetings he was always very respectful, mutually.

Despite the fact that I was 20, I would sit in the “suit” of a journalist and focus on that.

Also, the image of Videla that I came across was not the same as the one I had seen in books. Except for his look, which was the same: an impenetrable, hard look.

I came across an aged and older Videla. Nor was it so scary to see that person in front of me because I didn’t associate him with the Jorge Videla of ’76 that I saw in newspapers and magazines.

Q.: When was the last time you met Videla?

The last time I saw him was in the Bouwer prison, Córdoba. I came across a Videla “in his final stage”. I found him different, with a saddened look and physically bad.

Videla died at the age of 87 on May 17, 2013 in the Marcos Paz prison.

“A few months before deciding to publish the book, I contacted his wife to ask her how Jorge Videla’s death had been,” Cerone said. “She told me that she found out about the death of her husband on television, that he was alone in a cell lined with newspaper and isolated because he had received an anonymous letter that they were going to kill him; that it was wrong,” added the author.

“Videla, from what I perceived, was killed by the common jail,” the journalist sentenced.

Appointment with Videla 4.jpg

Source: Ambito

David William is a talented author who has made a name for himself in the world of writing. He is a professional author who writes on a wide range of topics, from general interest to opinion news. David is currently working as a writer at 24 hours worlds where he brings his unique perspective and in-depth research to his articles, making them both informative and engaging.