I have been working in the news industry for over 6 years, first as a reporter and now as an editor. I have covered politics extensively, and my work has appeared in major newspapers and online news outlets around the world. In addition to my writing, I also contribute regularly to 24 Hours World.

Menu

Middle East conflict on Tiktok: How German users spread fake news

Categories

Most Read

Baby in the Bundestag: Klöckner wants to support parents with children

October 16, 2025

No Comments

Ukraine receives new arms commitments from Europe

October 16, 2025

No Comments

Can Donald Trump simply move World Cup venues? That’s what lies behind it

October 16, 2025

No Comments

The situation at a glance: Before meeting with Trump: Zelensky receives new arms commitments

October 16, 2025

No Comments

Domestic political crisis: France’s prime minister has to face motions of no confidence

October 16, 2025

No Comments

Latest Posts

Nestlé cuts 16,000 jobs despite rising sales

October 16, 2025

No Comments

Food company Nestlé cuts 16,000 jobs despite rising sales Listen to article Copy the current link Add to watchlist Things are actually going well for

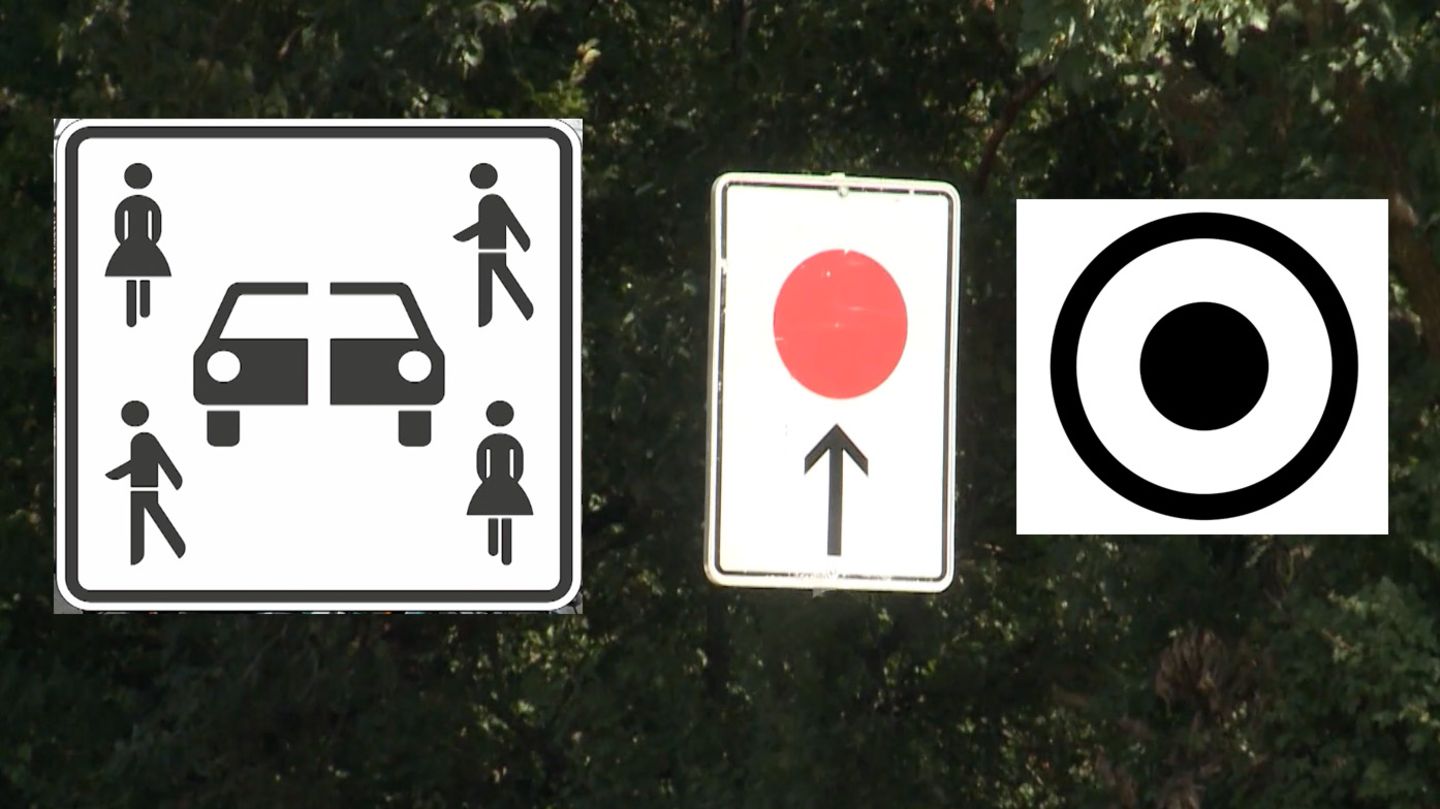

Traffic signs in focus: ADAC expert Lucà explains their meanings

October 16, 2025

No Comments

Only very few people know Do you know the meaning of these traffic signs? Copy the current link Add to watchlist Some traffic signs in

Driving license: Would you still pass the theory test today?

October 16, 2025

No Comments

Vera StackI’m a recent graduate of the University of Missouri with a degree in journalism. I started working as a news reporter for 24 Hours

24 Hours Worlds is a comprehensive source of instant world current affairs, offering up-to-the-minute coverage of breaking news and events from around the globe. With a team of experienced journalists and experts on hand 24/7.