I have been working in the news industry for over 6 years, first as a reporter and now as an editor. I have covered politics extensively, and my work has appeared in major newspapers and online news outlets around the world. In addition to my writing, I also contribute regularly to 24 Hours World.

Menu

Church: Revelation East: the unbelieving future for Germany?

Categories

Most Read

Climate change: They are homeless – and harbingers of a changed world

October 18, 2025

No Comments

Different way of dealing with AfD?: Merz: No AfD cooperation with me as party leader

October 18, 2025

No Comments

AfD will never be a partner for Friedrich Merz

October 18, 2025

No Comments

After criticism: Spahn defends Merz’s statements on migration in the cityscape

October 18, 2025

No Comments

are Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin digging a common tunnel?

October 18, 2025

No Comments

Latest Posts

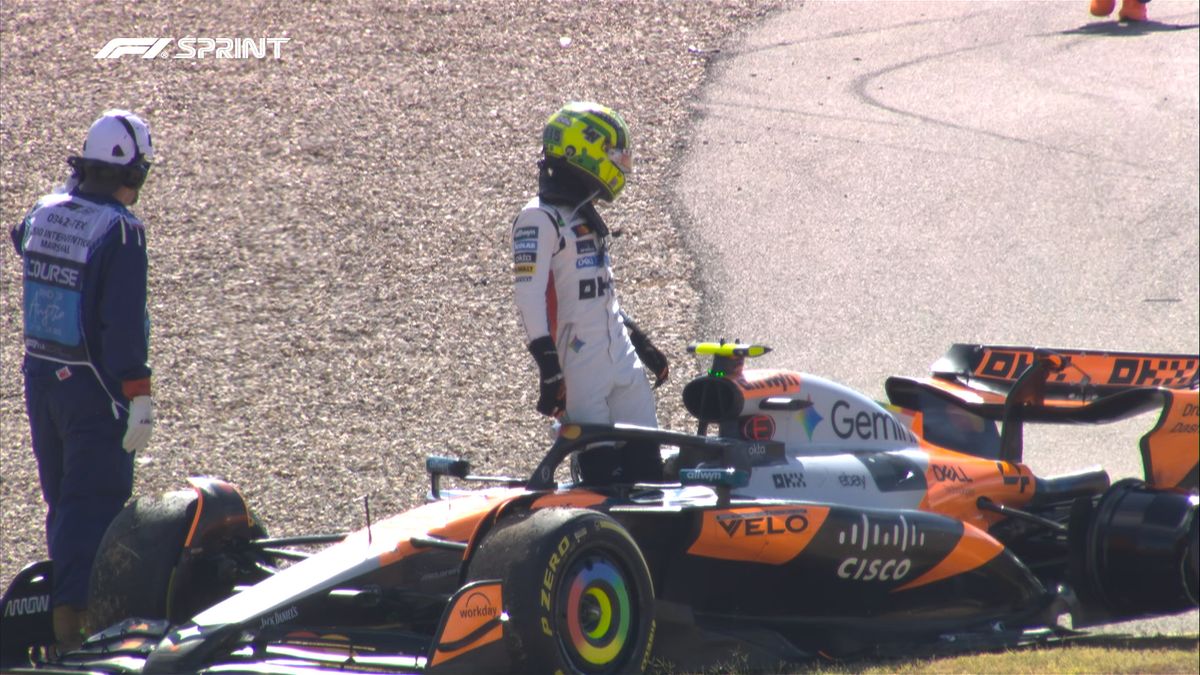

Formula 1: Sprint disaster for McLaren rivals – Verstappen wins with relish

October 18, 2025

No Comments

PierceI am Pierce Boyd, a driven and ambitious professional working in the news industry. I have been writing for 24 Hours Worlds for over five

Formula 1: the chaotic start of the US GP sprint race

October 18, 2025

No Comments

October 18, 2025 – 14:28 In the first corner, Nico Hülkenberg (Kick Sauber) was involved in an incident with Oscar Piastri and Lando Norris, from

On the seventeenth day of the closure of his government, Donald Trump once again faces a day of mobilizations against him

October 18, 2025

No Comments

A protest against the president donald trump It started in the city of New York this Saturday. It is the first of more than 2,500

24 Hours Worlds is a comprehensive source of instant world current affairs, offering up-to-the-minute coverage of breaking news and events from around the globe. With a team of experienced journalists and experts on hand 24/7.