Gregor Peter Schmitz takes a look at the magazine. This week it’s about Björn Höcke and a Forsa survey that looks at the state elections.

When the star When he interviewed the successful US author Jonathan Franzen last week, this fine observer of social developments called our Federal Republic a role model: “Germany takes full responsibility for its Nazi atrocities; there are even laws that prohibit symbols and slogans.” Franzen knows the country well, having lived here for years. Of course, his view remains one from the outside, although he sometimes sees more.

Yes, Germany can be proud of many things, even if it is currently fashionable to see our country as being on the brink of the abyss. These include our free media, functioning and independent courts, still existing popular parties, the broad acceptance of democracy. Berlin 2024 is not Weimar.

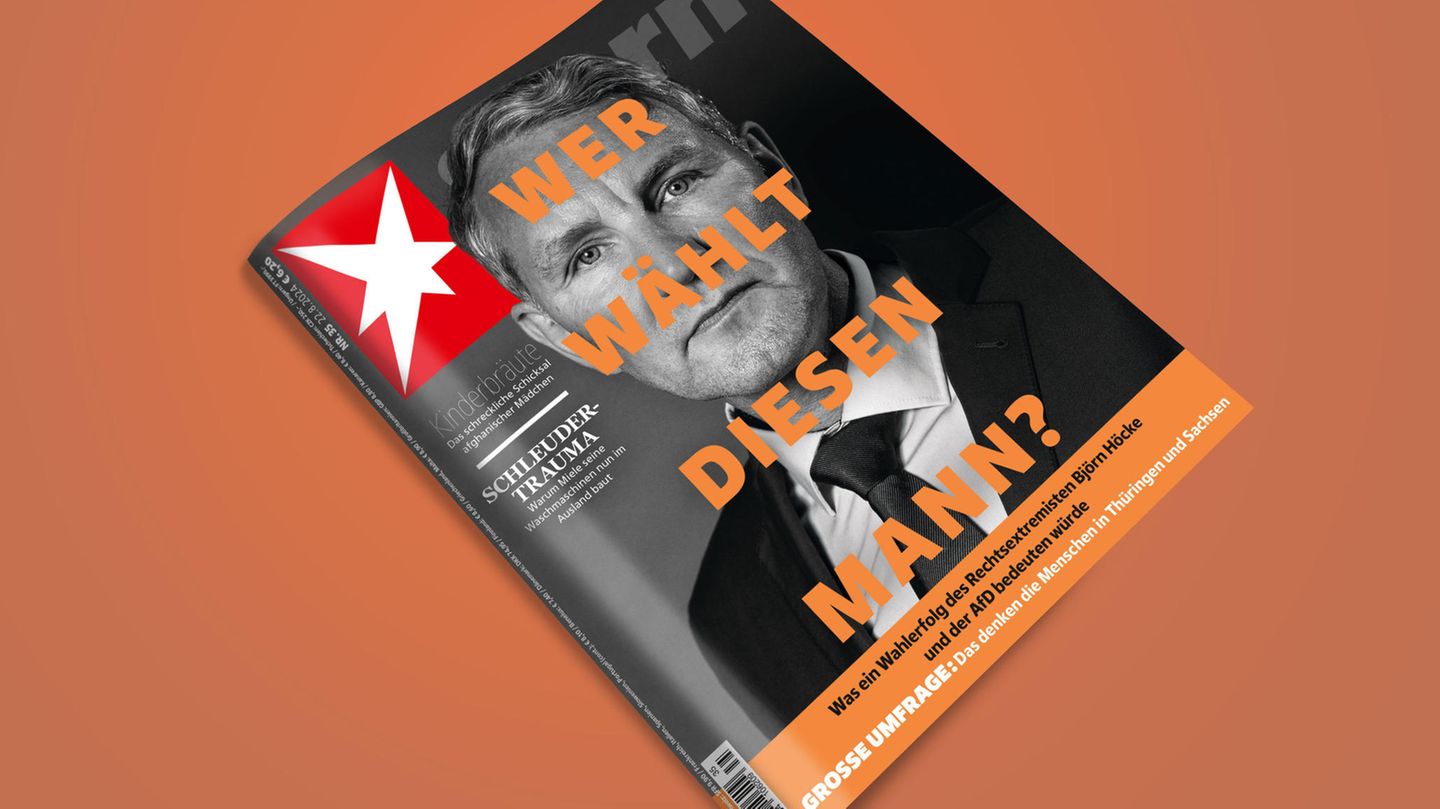

And yet, things are threatening to go wrong when the “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), a largely extremist association, is ranked second in the polls nationwide and could even become the strongest party in the state elections in Saxony and Thuringia, as a Forsa poll for star and RTL. This puts an AfD man, Björn Höcke, who can be called a fascist in court, at the centre and possibly in government responsibility.

Our cover story is not just about Höcke, but also about all those who might vote for him. What motivates these people?

The German division

For our cover author Martin Debes, who comes from Thuringia, the search for answers is a very personal matter. Debes shares the theory of the sociologist Steffen Mau, who says that Germany is “unequally united” because four decades of the GDR and three decades of transformation have created a kind of parallel society. He writes: “The dictatorship shaped people, through oppression, but also with propaganda. For most, the freedom they had achieved themselves brought new opportunities and prosperity. But many suffered from unemployment and loss of status. The consequences of deindustrialization, emigration and elite replacement are still having an impact. As a result, East Germans are on average older and less wealthy than West Germans; the proportion of men in the population is also higher than in the West. East Germans are significantly less likely to be organized in a union, church or party. They have a lower income, have fewer children. Their life expectancy is lower.” The list of complaints compiled by Forsa is long: the war in Ukraine, crime, immigration, inflation and social inequality are at the top. The threat of right-wing extremism or climate change is further down.

Debes sums up: “The mood in some places is correspondingly bad. A large minority feels second-class and left behind. Their trust in institutions is lower and their views are more radical. And that makes them more susceptible to populist and extremist movements.” Anyone who thinks this is an East German phenomenon should remember: the AfD also finds many voters in the West.

When a film star dies, I always have the same impulse: to watch all of his films. With Alain Delon, it’s a double challenge. Not only did he make a lot of films (more than 80), but he also made a lot of rubbish alongside undisputed masterpieces. In any case, Delon hardly missed a beat in his 88 years. But when he died, France seemed to stand still for a moment. So I thought again: other countries are gentler with their stars, with their strengths and weaknesses. Perhaps because they know that even big stars are people, and not always big ones.

Source: Stern

I have been working in the news industry for over 6 years, first as a reporter and now as an editor. I have covered politics extensively, and my work has appeared in major newspapers and online news outlets around the world. In addition to my writing, I also contribute regularly to 24 Hours World.