When they finally reached South Africa, he had a warrant for his arrest because he was underage (at that time, the majority was only 21). He quickly joined another, even smaller sailing ship, stopping at St. Helena and other islands until reaching a port in Virginia. “Like someone arriving at Tigre or San Fernando, a port full of little boats. I got off, nobody asked anything, I took a bus and ended up in Charlottesville. I have lived there for almost 50 years.”.

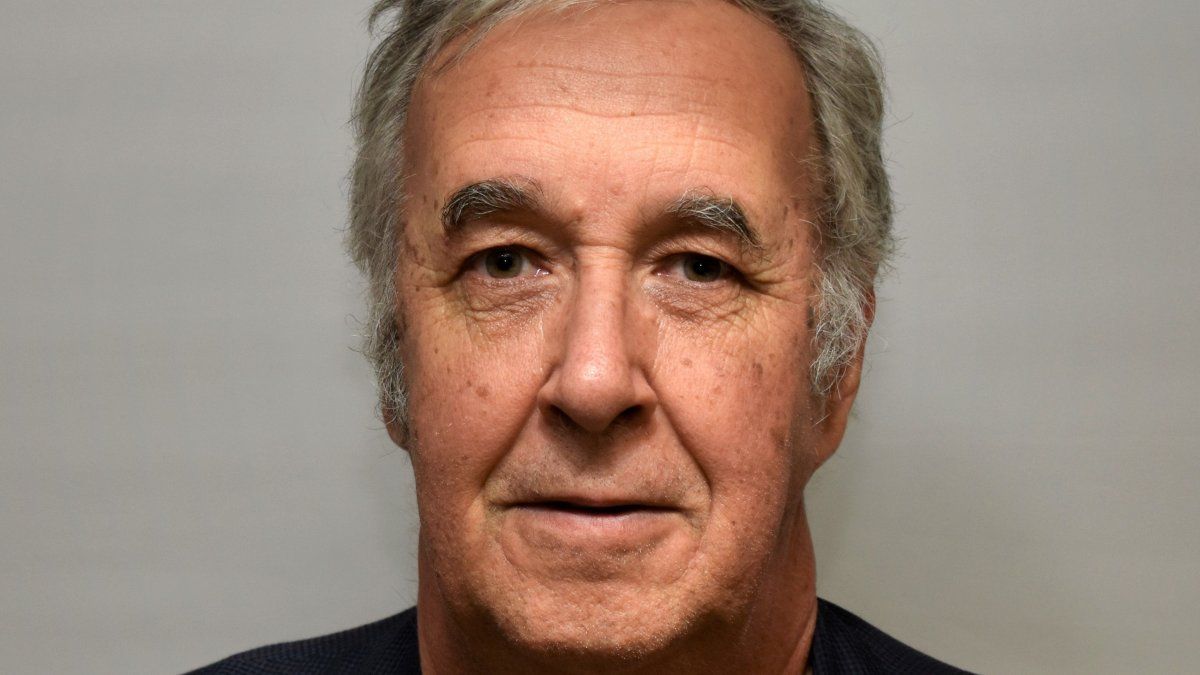

There he also fixed his situation, studied, became an agricultural engineer, and almost 25 years ago he moved into film as a producer (the celebrated “Mondovino” of Jonathan Nossiterseveral National Geographic titles, including Argentine ones “Goodbye, dear moon” and “Tango, a strange turn”) and documentary filmmaker (“Chagas, a hidden evil”, “The Patagonian Bones”, “Returning home”, “From Nubia to La Plata”).

Today he premieres his new work here, “Someday somewhere”which boasts the curious record of having been rejected at dozens of American festivals. Its theme: the current relationship of Americans with Latin immigrantsThe film will be shown today at the Gaumont, in some squares in the interior, and shortly afterwards at the Cosmos, which is about to reopen. We spoke with him:

Journalist: What was your own experience like as an illegal immigrant when you were young?

Ricardo Preve: Very nice. They didn’t even know where Argentina was or what language we spoke, but they were all very friendly. At the University of Virginia they simply told me “Sign up. You’ll sort out your papers.” That’s how it is there, most people are good, the “hachedepé” are few. But they know how to handle the rest. The big change for immigrants has two dates. 9/11/2011 was the trigger, when many, in their ignorance, began to put all dark-skinned foreigners in the same bag. That’s when prejudices were ignited. And on 1/6/2021, when Trump gave his support to those who stormed the Capitol, that was the legitimization of violence against immigrants.

Q: Violence that had already been going on for some time.

RP: We wanted the film to be non-partisan. Barack Obama himself deported more people than anyone else. The legislation has been bad for years, it allows serious exploitation. The immigrant leaves a country that offers him no future or security, he makes a difficult journey, they fleece him at the border, he can only enter illegally, and once in the US he can work but if he is not paid afterwards he has nowhere to complain. He also has no health care and lives in fear of being deported for the slightest reason. His children can go to school, but they don’t know if their parents have not been arrested and deported when they enter the home. That is done very quickly. Legalization takes years. The worst is when they imprison the parents on one side and the children on the other. Sometimes they are very young, they don’t even know their parents’ last names or who could help them and they end up alone in the world. Sometimes, with luck, someone adopts one of them.

The two faces

Q: You paint this hell in the first chapter. The second chapter shows another kind of Americans, dedicated to helping the needy through various religious or secular organizations. You also draw parallels with the story of Irish immigrants in the 19th century, and the internal migration of peasants from Oklahoma to California after the great dust storms and subsequent drought of the 1930s.

RP: To do this, we use fragments from a classic Hollywood film that portrays that period, John Ford’s “Grapes of Wrath,” starring Henry Fonda, which depicts very well the work in the black market for a few coins, the contempt of other people along the way (the dialogue between the two prejudiced employees in the scene at the gas station is painfully current), and we are talking about compatriots displaced by a historic drought. Today, climate change is pushing for even greater exoduses in various parts of the world. That, added to gang violence or wars and other evils, make people escape the hell where they live to risk living in another hell where they are not welcome but, with effort, they can improve their situation. Or so they hope.

Q: The ending is hopeful. It is even in color and with the Gloria from La Misa Criolla. But before that we learn some pretty strong things.

RP: Some testimonies were left out to avoid possible reprisals against the person who spoke. We had all of them sign a photo permit beforehand, except for two whose names were not written down, so that later the Immigration authorities could not locate them so easily. Several Argentines traveled especially to do photography, art, sound, and in addition to “Viñas…” we included photos of the admirable Dorothea Lange, lines from a poem by Emiliano Pintos, and other details so that, in addition to the content, the work also had good formal quality, and I think we achieved that.

Q: It’s one of the best you’ve made so far. How was the episode about the children’s poems filmed?

RP: Seth Michelson, a poet and translator, managed to do poetry workshops with children and teenagers who are imprisoned only for having entered illegally. With them he made an anthology, “Dreaming America. Voices of Undocumented Youth in Maximum-Security Detention.” We were not able to film them, nor record their voices. What you hear are the voices of other children, and what you see is a prison abandoned in 2020 due to the pandemic.

Q: It just gives you an idea. Was everything filmed in and around Charlottesville?

RP: That’s right. We wanted to tell big stories through small, everyday things that are around us. For example, showing the Italian pizza maker who lived in Argentina and is a reader of Borges and Dostoevsky. I love that, because many people think that immigrants are all illiterate. There’s the Guatemalan radiologist Max Luna. His neighbor thought he was just a nurse. And the Cuban who arrived on a raft and now works as a policeman.

Q: By the way, the conversation with the police chief, an unexpectedly open-minded guy, was very interesting.

RP: We wanted to show that there is everything, good people and the other kind. And that immigrants make great contributions to culture, knowledge and work. Many do not want to recognize it, but they are fundamental. There is a lot of hypocrisy. For example, 30% of the baseball players in the major leagues are Hispanic, and no one questions them. Another example: once the police expelled several farm workers and the leaders of the associations of apple and peach producers immediately chartered buses to rescue them before they crossed the border.

Q: I’m thinking about the comedy “A Day Without Mexicans” by Sergio Arau.

RP: That comedy has a great proposition! What would happen if all the Hispanics in California suddenly disappeared? The economy would collapse. Imagine if it happened all over the country.

Q: It was a success in Mexico, but in the US it was seen by very few people. What audience do you have in mind for your film?

RP: We already showed it at the Virginia Film Festival organized by the University. A room with more than 500 seats. There we found that it already has two kinds of audience: those who cried and came up to thank us, mostly immigrants, and the white supremacists who threatened us. The police had to protect us. In truth, they did not enter the room. They did not see it, which did not prevent them from expressing their opinion. Then many festivals rejected it to avoid problems. But now we are in talks with a distributor who plans to put it on a large platform, if possible before the elections. Here for now we will premiere it at the Gaumont and some theaters in the interior. And soon at the Cosmos cinema, which is going to reopen. There are also three provincial television stations that are already programming a retrospective of my other films.

Q: And it doesn’t premiere simultaneously on Cine.ar, as is usually the case?

RP: No, because only those with Incaa production go there.

Source: Ambito

I am an author and journalist who has worked in the entertainment industry for over a decade. I currently work as a news editor at a major news website, and my focus is on covering the latest trends in entertainment. I also write occasional pieces for other outlets, and have authored two books about the entertainment industry.