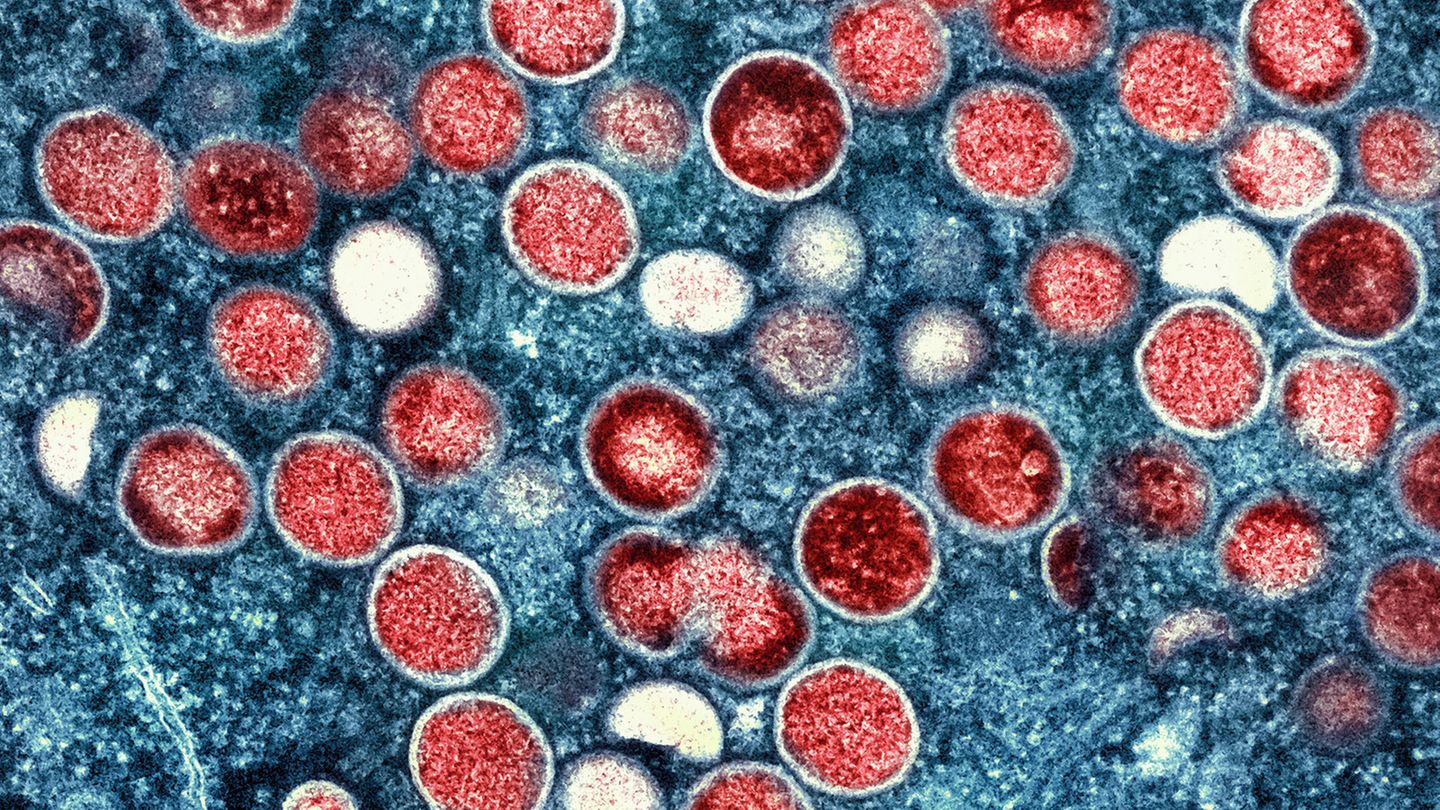

After an unusually high number of Mpox (“monkeypox”) cases and the discovery of a new subvariant, the World Health Organization is considering declaring a health emergency. What that means.

The numbers alone show how worrying the situation is on the ground. The African Union Health Agency (Africa CDC) recorded 14,250 cases of Mpox – formerly known as “monkeypox” – from the beginning of the year to the end of July, almost exactly as many as in the whole of last year. But even then, an increase of almost 80 percent compared to 2022 had already been observed. Since then, the number of infections has risen exponentially.

Almost all cases currently come from the Democratic Republic of Congo, including 450 of the 456 fatal cases that were reported in the first seven months of this year alone. However, the first cases are now also occurring beyond the borders of Congo, for example in the Central African Republic, Rwanda, and also in Cameroon and Nigeria. As the Africa CDC announced in a briefing, 16 African countries are now affected by the Mpox outbreak and another 18 countries on the continent are at risk.

How Mpox (“monkeypox”) is transmitted

Infection occurs through close contact with infected animals or people. After an incubation period of 5 to 21 days, symptoms of the disease can appear, usually pox-like rashes, either locally or all over the body. The vast majority of patients have recovered after two to four weeks. However, there are also severe cases with high fever and swollen lymph nodes and, in the worst case, fatal infection of the organs, especially the spleen and liver.

African experts see frequent sexual contacts, co-infections with HIV, for example, as well as malnutrition and the associated immune deficiency as key risk factors. Sex workers and their clients, as well as men who have sex with men, often become ill. The latter group in particular was affected in Western countries during the 2022 outbreak.

Because MPXV, the abbreviation for the virus, was first discovered in a Danish laboratory in 1958 in monkeys from Singapore, but monkeys are not the most important carriers of this virus in nature, the WHO replaced the long-used term “monkeypox” at the end of 2022 with the neutral and now also common “Mpox”. The virus probably passed to humans decades ago via native rodents. The first cases were discovered in several African countries in the 1970s. Children were also often affected, probably because they ingested the pathogen via excrement from infected rodents while playing. Sex is therefore not a prerequisite for infection, although it is probably the most common route of transmission. And every new transmission gives the pathogen the chance to change and adapt to new conditions.

Based on its genetic makeup, the virus can be divided into two groups, which are called “clades” in technical terms. These virus families, known in Roman numerals as Clade I and Clade II, are so similar to each other that the MPXV genome sequences, which consist of around 200,000 genetic “letters”, are more than 99 percent identical to each other. And the similarity to other types of smallpox is also over 90 percent.

But even the small difference can have significant consequences. This is especially true with regard to the course of the disease. Clade II viruses are usually less harmful. It was such viruses (“Clade IIb”) that led to the major outbreak in West Africa in 2022 and 2023 and ultimately to almost 100,000 infections in a total of 116 countries worldwide. Germany was also affected with around 3,800 cases, most of them between June and September 2022. After that, Mpox was only diagnosed sporadically in our country. In Africa, however, new cases repeatedly occurred in larger numbers.

More dangerous viruses are currently circulating

This time it is the more dangerous viruses of Clade I that are spreading more and more in Africa. In the Congo Basin, a mortality rate of a good 3 percent of cases was observed for this genetic group. In the past, however, case fatality rates of almost 11 percent have also been observed. In Clade II, on the other hand, only about 0.2 to a maximum of 3.6 percent of infections were fatal. But viruses change. In April, samples from the Kamituga mining region in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo had already revealed Mpox pathogens of a new sub-variant from Clade I. This new genetic group is now called “Clade Ib”. Not only are the disease courses it causes generally more serious than those of Clade II. Within Clade I, mutations are now appearing in a region of the genome that particularly promotes person-to-person infection. The virus is therefore constantly adapting to its new host.

As early as 2022, a Portuguese research team had discovered a mutation rate in this genetic region of the Mpox virus that was six to twelve times higher than experience with such poxviruses would have led us to expect. Mutations occur randomly, like typos, and the virus often does not survive such genetic blunders. However, a mutant can also emerge that has an evolutionary advantage and can, for example, be transmitted more easily from person to person than older viruses of this type. Unfortunately, this seems to be exactly the case with clade Ib, which is now spreading in Central Africa. From the known mutation rate and in comparison with previous samples, it can be assumed that this subvariant of MPXV first appeared in July 2023 at the earliest and has been spreading since then.

WHO: Is there a global health emergency?

It is therefore only logical that authorities such as the Africa CDC and the World Health Organization are closely monitoring developments and taking precautions to contain the virus as quickly as possible. The WHO now wants to prevent the virus variant from clade Ib from spreading globally and may even declare a global health emergency to do so. This is the highest warning level available to it under its statutes, the official name: “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” (PHEIC), i.e. a health emergency of international concern. Covid-19 also had this official status.

But this is by no means synonymous with a new pandemic, but above all gives the WHO the opportunity to act in an internationally coordinated manner to prevent things from getting worse. The WHO Director-General and all 194 contracting states are legally obliged to implement the measures recommended by an emergency committee made up of suitable experts. Both the US infection control agency and its European counterpart currently consider the risk posed by the new Mpox sub-variant to be very low in their respective regions. But it would be fundamentally wrong to sit back and relax. Because the virus doesn’t take a break either.

That is why the WHO recently presented a strategic framework for the global containment and control of Mpox for the coming years up to 2027. An effective vaccine already exists, even if exact figures for such a supposed niche product are lacking. A recent review article evaluating the studies available to date finds protection against severe symptoms at almost 60 percent. No serious side effects were observed. However, it is not clear to what extent the vaccine also reduces the risk of infection itself. “Imvanex” is the only smallpox vaccine approved in the EU, but was not available during the 2022 outbreak, for example. A closely related product from the same manufacturer (Bavarian Nordic A/S) had to be used and imported from the USA under the name Jynneos. But these stocks were also very limited due to the sudden global demand.

Such shortages should not be repeated. In addition, there is a lack of additional studies on the likely waning effectiveness of the vaccines. Better vaccines should be developed and, if possible, antiviral drugs, according to the WHO in its preparedness plan. After all, a PCR test has just been introduced that can already pick out the new clade Ib viruses from their genetic relatives and track their further spread.

Yes, all of this costs money. But Mpox are a good example of why pandemic prevention is an indispensable investment in the future – and why it can be very dangerous to put off such investments. If it is not the Mpox pathogens that surprise us tomorrow, then perhaps it will be bird flu or some virus that no one knows about yet. US virologist Anthony Fauci, known worldwide for his HIV research and the corona pandemic, summed it up two years ago in a cautionary article for the “New England Journal of Medicine”: “It’s not over until it’s over … but it’s never over.”

Source: Stern

I’m Caroline, a journalist and author for 24 Hours Worlds. I specialize in health-related news and stories, bringing real-world impact to readers across the globe. With my experience in journalism and writing in both print and online formats, I strive to provide reliable information that resonates with audiences from all walks of life.